A Crisis of “Bigness”

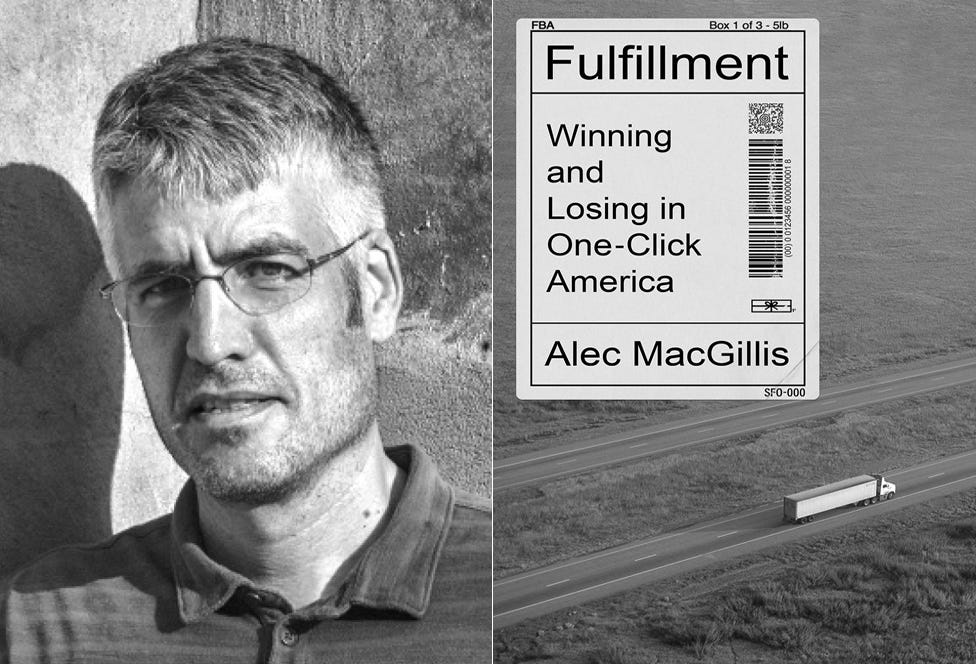

A review of "Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America" by Alec MacGillis

Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America

Alec MacGillis

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 400 pages, 2021

The 21st century, no less than the 20th, will be shaped by how it responds to the “curse of bigness.”

The idea isn’t exactly new; Louis Brandeis first used the term over a century ago, looking on at an American economic landscape of exploitation and monopoly. Despite the thousands of pages in Brandeis briefs as the “People’s Lawyer” and despite the rulings that earned him, as a Supreme Court justice, the moniker “old Isaiah,” his victories were only delaying actions. The thrust of history has been centrifugal and consolidating.

Jeff Bezos’s Amazon might as well be one of his nightmares come to life.

The curse of bigness, after all, was never just about economics—or even scale. Brandeis voted as part of a unanimous Supreme Court to overturn much of the First New Deal in 1935: “This is the end of the business of centralization,” he declared to FDR advisor Tommy Corcoran in a statement that now appears as futile as Bill Clinton’s declaration that the era of big government was over. While he favored progressive reforms and politicians throughout his life, he never shared the movement’s technocratic faith in government, experts, or anything smacking of paternalism.

Thomas Jefferson was one of Brandeis’s first major intellectual models and, like Jefferson, Brandeis’s wariness of centralization grew from beliefs about citizenship—about place. To his mind, citizenship was a key marker of the good life. It would emerge locally, from the ways in which the specific character of specific places teaches self-government. Only then could we truly become masters of ourselves—and our nation.

Untrammeled bigness of the sort that Amazon sought and now possesses doesn’t just lead to market control, but the erosion of distinct places and the opportunities they offer to grow as citizens. That’s what Brandeis might have foreseen and what Alec MacGillis explores in Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America.

In the 21st century, the curse of bigness is less about the consolidation of wealth as it is about the consolidation of opportunity. “Put most simply,” MacGillis explains, “business activity that used to be dispersed across hundreds of companies large and small, whether in media or retail or finance, was increasingly dominated by a handful of giant firms. As a result, profits and growth opportunities once spread across the country were increasingly flowing to the places where those dominant companies were based.” The result, he sees, is “a country segmented into different sorts of places, each with their assigned rank, income, and purpose.”

Brandeis told Corcoran that centralization was finished, but he also offered advice to the president and his advisors: just because the New Deal had crossed constitutional boundaries didn’t mean there wasn’t work to be done. “As for your young men,” he told Corcoran to tell Roosevelt, echoing the advice he frequently gave his law clerks, “you can call them together and tell them to get out of Washington—tell them to go home, back to the states. That is where they must do their work.”

Today, the problem isn’t so much that Greater D.C. has become such a hub of work and opportunity for the ambitious smart-set—that its 20- and 30-somethings would be confused by the prospect of finding better, more fulfilling work elsewhere—but that in many cases there is nowhere for them to return.

To adapt the cliché, it’s not about the choice between being a big fish in a small pond or being a small fish in a big pond, but that all the small ponds have been drained. That’s something Brandeis never worried about—the ecosystems might fall out of order, but they’d still be there.

The evisceration of local and regional economies—the death of manufacturing as well as main street business districts—didn’t begin with Amazon, of course. It’s the scale that’s new.

“Regional department stores, you used to have regional everything, right?” MacGillis quotes an early Amazon investor, eyes now wide, observing. “Some of those people who owned those companies were greedy fucks, too. But at least … there was an anchor of prosperity in those places. But now everything is in Seattle or San Francisco or Los Angeles or Chicago, and all that stuff got sucked out.”

Unlike other recent broadsides against big tech, MacGillis hasn’t assembled a legal, theoretical, or economic examination of the industry but an exploration of the lives of places and the people who live in them. And the heroes of his account are those who try to resist the centralization of opportunity (the centralization of fulfillment, we might say)—those who choose to stay home and struggle for place and community.

Chief among these is Taylor Sappington, from the small, southwest Ohio town of Nelsonville. Sappington briefly attended George Washington University in D.C., but, out of place among his peers, realized he didn’t want to be like them.

So he returned home to attend Ohio University, a private liberal arts college in nearby Athens. Despite his degree, there simply wasn’t much work in and around Nelsonville—unless you want to drive to Columbus, the state’s affluent, educated, tech-era boom town. (But then, why not live somewhere closer if your job means you can afford it?) So he waits tables at the Texas Roadhouse but has carved out a small role, first as a city councilman and, now, as city auditor.

But the crisis of small communities, places in flyover country, what half the nation might call “Real America” and the other half “Trumpland,” goes beyond what’s increasingly well-known about Amazon: its mob-like extortion of retailers on its marketplace and the workplace hazards faced within its warehouses and distribution centers. Indeed, the bulk of Fulfillment explores these, both through those who try to get by while working in fulfillment (as Amazon calls it) and the businesses that try to adapt and survive.

Yet in many ways they’re only symptomatic. Treating them will improve lives, but won’t resolve the crisis of Amazon’s bigness.

That’s because the last 40 years saw the gradual and then rapid shift, in precisely these places, from a manufacturing economy to a distribution economy. The places, that is to say, which used to make things now merely ship them. Those who might, in another generation, have had the opportunity for employment as skilled laborers now earn less to move boxes as rapidly as possible.

But a bad job is still a job—and cities, in their desperation to attract logistics hubs, offer tax easements and exemptions that help bring them in but ultimately lead to the erosion of local tax bases. It’s all fine and good for a Taylor Sappington to choose to fight for Nelsonville—but the consolidation of opportunity also means that there are fewer and fewer resources available to even attempt adequate self-government.

The same’s true for Amazon’s flashier side, the data centers that power Amazon Web Services and the cloud-computing branches of other major companies. The jobs these centers bring to Northern Virginia are certainly better than those Fulfillment brings to southern Ohio, but they also undermine the ability of the place to organize and govern itself—to build a sustainable local economy or community.

And this is to say nothing of Amazon’s paternalism which, like that of the tech industry at large, seeks to make our choices for us—what Harvard Professor Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism.”

Unlike Google and Facebook, Amazon has never had the problems that come with being free—the pervasive sense that if you’re not paying, then you might just be the real product, sold to advertisers. From its start, Amazon is—and has been—transactional in a more conventional sense: you purchase a book or pay each month for Amazon Prime, transferring money in exchange for goods and services. If Amazon has typically been more popular with the American public than its main tech rivals, perhaps it’s simply that it seems normal.

Of course, this understanding of where and how tech giants make their money (and accrue their power) is wrong, Zuboff insists. Her major insight in The Age of Surveillance Capital is that you and I aren’t Facebook’s or Google’s products; we’re the raw material for the true product, the ancillary data they glean about us, which can then be packaged and sold not merely to optimize ad targeting, but to enable companies to “nudge” us to their products by anticipating what we might want. Zuboff refers to this as “behavioral surplus”: extra information about our behavior created by actions like a search, a click, or a purchase. The market for this surplus data is where the real money lies. It’s not about the fulfillment of desire, but its creation.

Despite its conventional surface, this is true of Amazon as well. In fact, its access to this kind of data is the key to its market strategy. It’s not just that Amazon is able to charge extortionate rent on businesses that sell on its platform—at 15 percent, it wipes out the profit margin for many small businesses—but that its access to both sales data and behavioral surplus grant it an extreme advantage in its direct competition with its marketplace sellers: which items to produce itself, price optimization that sometimes fluctuates by the minute, and the ability to nudge customers toward its preferred products.

Amazon doesn’t only do this to local and regional businesses. Through Amazon Web Services, which provides cloud-computing and data-storage services, the company plays host to huge swathes of the supposedly independent internet: its clients include GE, Verizon, Apple, Netflix, and News Corp, among many others. Amazon, MacGillis observes, has “slapped a meter on the side of the nation’s data centers, except without the regulatory limits that utilities faced.”

Fulfillment, ultimately, isn’t an attempt to “expose” Amazon—though that’s how it’s often described. Few of the stories MacGillis tells are truly new; rather, he takes the kinds of stories that might otherwise have only appeared, briefly, in the dying shoots of local journalism and creates a compendium with a national audience.

But this is also because Amazon alone, or even the tech industry alone, aren’t to blame for the crisis of bigness that MacGillis sets out to expose, even if they’re its worst sinners. Fulfillment tries to tell the story of the 21st century as the story of a single word: how we moved from thinking about fulfilling lives to thinking about fulfilling orders.

It’s a helpful rhetorical move, but it’s also a bit too simple—and anachronistic. Both the individualist definition and the economic one date from the 19th century. Yet if either of them is the newcomer, it’s actually the notion of personal fulfillment, which, the Oxford English Dictionary notes, came into prominent use only in the last hundred years. Brandeis, for example, didn’t write about fulfillment but the mastery of skill and self. “It is only when working within limitations, that the master is disclosed,” he liked to say, quoting Goethe.

Even if a narrative in which economic fulfillment replaces personal fulfillment doesn’t hold up, the two definitions do compete. Indeed, we can see each as the encapsulation of a worldview: economic man against the person whose life is oriented around “satisfaction or happiness as a result of fully developing one’s potential or realizing one’s aspirations,” a dictionary definition that reads like something from an Anthony Kennedy decision.

The tension between these two meanings has replaced a much older understanding of fulfillment. We speak more often of fulfilling orders and fulfilling lives than we do of fulfillment as the act of completion or accomplishment: the fulfillment of prophecy, promise, or mission; the fulfillment of potential and talent; fulfillment of vows, duty, and obligation.

Fulfillment once was a word that helped us understand our own embeddedness—a word that described the ways we were bound to other people and within wider networks. Personal fulfillment, economic fulfillment—each is exactly what it says it is. They’re only in tension, in competition, in the way that two sides of the same coin are. Only one can land face-up.