Allegories from the Underground

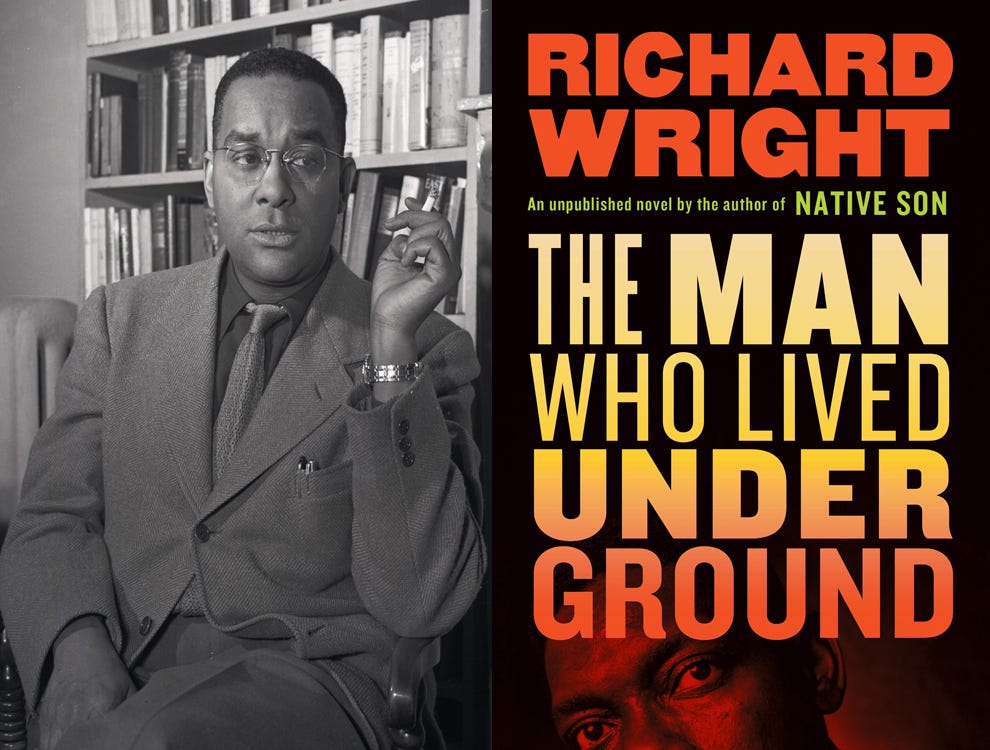

A review of "The Man Who Lived Underground" by Richard Wright

The Man Who Lived Underground

Richard Wright

Library of America, 240 pages, 2021

One of this summer’s major literary events is a novel that’s already 80 years old: the first complete edition of Richard Wright’s The Man Who Lived Underground. Intended as his follow-up to Native Son (1940), it only made it into print in a much-abbreviated version: as a short story best known for helping inspire Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. That’s because, in part, as a surrealist allegory it’s strikingly different from the books on which Wright built his reputation and on which it still rests. Both his agent and publisher disliked the novel, convinced Wright was wandering down the wrong path.

Some of this early criticism still holds: Anyone looking for the hard and violent certainty of Wright’s most famous works will be disappointed. The early shifts in style and tone are disjointed; outside of its protagonist, characterization is mostly flat. The novel remains as it was when Wright set it aside: still unfinished.

But this is 2021, not 1941: one year after an uneasy summer of protests for racial justice; one year after Americans burrowed into our own pandemic undergrounds from which we’re just now starting to emerge. It’s too early for pandemic fiction and for the protest novels of Black Lives Matter—too soon to step outside of life and observe it from a distance, as both Wright and his titular protagonist do. The Man Who Lived Underground is at once a story of police violence and of a world in which objects of everyday life cease to hold their regular meaning

A “Tale for Today,” the headline on a New York Times review announced; the jacket copy casts Wright as a prophet offering “AN INCENDIARY NOVEL ABOUT RACE AND VIOLENCE IN AMERICA.”

The Man Who Lived Underground has two birthdays: and as different as 1941 and 2021 are, they share something important. Both have felt like times in which there’s little if any room for uncertainty or error. 2021, whatever else it may be, is a year in which we choose facts along with political teams: about Covid, masks, and vaccines; about police and crime; about lab-leak theory; about January 6; about Israel; about anything and everything. When the personal is the political, there’s no exit: it’s not so much that you must take a stand but that everything you do announces your stance even if you don’t yet realize it.

Eighty years ago, Wright wrote from the midst of a personal and political crisis of faith, his break with the Communist Party at its center. This uncertainty informs the novel. Far from the successor to Native Son he told his publisher he was writing (a long, naturalist work about domestic workers), The Man Who Lived Underground circles around knowledge and doubt. In its much-discussed, newly-restored scene of police torture, it is less physical brutality than “the terrifying feeling that these men knew what he would be doing at any future moment of his life, no matter how long he lived” that shapes the officers’ power. Certainty is power. It almost lets one control the future.

Racial violence and police brutality are only some of the areas drawn into the book’s vortex. This edition honors Wright’s vision for presenting the novel: it is 159 pages followed by the 50-page essay-commentary-memoir, “Memories of My Grandmother.” The essay is an elegant discussion of literary craft and insistence on the artistic merit of African-American song—and a firm push to read the novel’s allegory capaciously. Wright highlights what the novel itself observes more quietly: even police violence and racism so fundamental that, today, we’d call them systemic or structural, are roads that lead to a more existential question: Why do we feel guilty?

This is as religious a question as it is political and leads Wright windingly through Freud and surrealism, jazz improvisation and blues structure, back to the strict religion of his grandmother’s Christianity—and Plato’s allegory of the cave, in which we find, at the heart of political philosophy, men who live underground.

Picture a man dwelling in a sort of subterranean cavern; it can only be entered if the seal is lifted from one of an irregular series of holes in its ceiling. There is almost no light at all in this cave. Conceive of this man as being totally unfettered, able to move about as he wishes. In this darkness the man can barely see, must work from touch, balance, memory, the occasional hazy beam from above that “threw everything into such a peculiar light”—yet he grows more and more curious: he wants “to know more about what lay at the end of these mist-shrouded labyrinths.”

From time to time, he emerges into the aboveground. It’s always hard to tell what the purpose of a given building is: an undertaker’s, a grocery, the basement of a movie theater. In the last, he sees others, seated as if their heads are fixed permanently, maybe chained, to stare at a wall on which images are projected. A light flames out from above their backs. They are, he concludes, “laughing at their lives, at the animated shadows of themselves.”

Aboveground, this man had been called Fred Daniels and he used to be like them. He fingered the 17 one-dollar bills in his pocket as if they were precious gems; now he pastes hundred dollar bills (stolen from the safe of an insurance company) as wallpaper in his cave, then bedazzles them with diamonds (he tunnels into a jewelry store as well). Once, he feared firearms; now, he’s fired a night watchman’s pistol just to hear its noise: a blinding light, pointless clatter, the perfect embodiment of the ways people hide from knowledge aboveground.

On the day that led him to the sewers, he was in a hurry to get home—his wife was due to give birth at any moment—when three police officers stopped him and hustled him into their squad car. A double-murder had taken place next door; here, they think, is a young black man in the right place and the right time. All in a day’s work.

For the next 50 pages, they interrogate, beat, and torture him. He’s barely conscious when they guide his hand through the motions of a signature, copying the form of the one on his Selective Service card as best they can. He knows he has to escape them—and he does; they’re bad cops as well as racist ones (these appear inseparable)—but comes to believe they’ve given him, through all this, meaning.

Now, for the first time in his life, he knows who he is: He “was guilty; though blameless, he was accused, though living, he must die; though possessing faculties of dignity, he must live a life of shame; though existing in a seemingly reasonable world, he must die a certainly reasonless death.”

This epiphany drives Daniels to offer himself as a universal scapegoat; he feels what Wright calls, in “Memories of My Grandmother,” “an abstract, all-embracing love for humanity.” But humanity itself has become abstract for him: people have ceased to be individuals. One of the officers who beat him interrogates the night watchman on duty when Daniels robbed a jewelry store, but peering in on this scene, he feels he isn’t watching a man being tortured, but a movie of this—though he doesn’t laugh, the lives of others have become merely “animated shadows,” no more real than what’s projected on a cinema screen.

Going underground lets Daniels see the absurdity of the symbols of life aboveground—but offers him no actual truth to replace them. His abstract love for humankind, like that of Wright’s Adventist grandmother, is inseparable from “callousness toward others, this disdain of things relating to the life of society as a whole.” He forgets even his wife and newborn child.

Like the escapee from Plato’s cave, Daniels returns to his chained and fettered companions and they think he’s gone mad. As his seriousness dawns on them, they too turn violent. But Plato’s escapee—at least in the world of his allegory—has seen fundamental truths about the world as it is. Daniels has only partially apprehended something: the ways in which, aboveground, we clamor for caves to chain ourselves in; the meaninglessness of the items (money, jewels, guns) that seem to give life meaning there. But people, too, have become abstract and meaningless. We’re all guilty. We must all be punished.

Pop Quiz: read the following paragraph and identify its author.

“When a man is accused, he is already condemned in the minds of the people who launch the accusation, all the fine and fancy Bill of Rights to the contrary. It is a psychological law. No man will accuse another, rightly or wrongly, unless he has already cast that man beyond the pale of the just and honest and decent.”

(A) Brett Kavanaugh, during his confirmation hearing

(B) Donald Trump, during his first impeachment

(C) Attorneys for a “John Doe” in a campus Title IX investigation

(D) Advocates for police reform in July, 2020

(E) All of the above

(F) None of the above

The correct answer is F, of course: these words are Wright’s, appearing near the end of “Memories of My Grandmother.” But that E is even plausible—that we can hear this statement, one of the driving psychological premises of The Man Who Lived Underground, in the voices of today’s right and left—helps us better understand its draw as political allegory for this moment.

Wright refracts his examination of guilt and accusation through the experiences of black men in America. “After all,” Wright himself feels the need to remind readers, “Fred Daniels is a Negro, and Negroes in America are accused and branded and treated as though they are guilty of something. They don’t know what they’ve done to be treated so.” The Man Who Lived Underground, that’s to say, isn’t simply an attempt to understand the psychology of a specific man who has been falsely accused of a specific crime—but an attempt, as well, to understand the psychology of a class of people whose very existence can feel like, can be, an accusation against them.

The novel’s ending suggests there’s no exit short of apocalypse. Wright’s own actions belie his worry that this might be true: in 1945, he left America for Paris, where his daughter and grandchildren were raised.

And yet Wright also wants us to understand the psychology of accusation in more universal terms. “No man will accuse another,” he insists, “rightly or wrongly, unless he has already cast that man beyond the pale of the just and honest and decent.” To the extent that Fred Daniels becomes a hero, it’s in this: he steps outside of a cycle of accusation in which, to respond to our own feelings of guilt (earned or not) we look for others to be guilty on our behalf. Instead of accusing another, he offers himself for punishment. He can’t feel for others anymore, or even see them as truly human in the way he sees himself, but he can refuse to cast them “beyond the pale of the just and honest and decent.”

The problem with accusation is this: among those who brook nothing but certainty, whether that’s 1941 or 2021, the record books can’t concede error. Even when the accusers acknowledge that they got it wrong, they have to destroy the evidence. “You got to shoot his kind,” one officer says of Daniels. “They could wreck things.”