Building a Legacy

A review of "If Walls Could Speak: My Life in Architecture" by Moshe Safdie

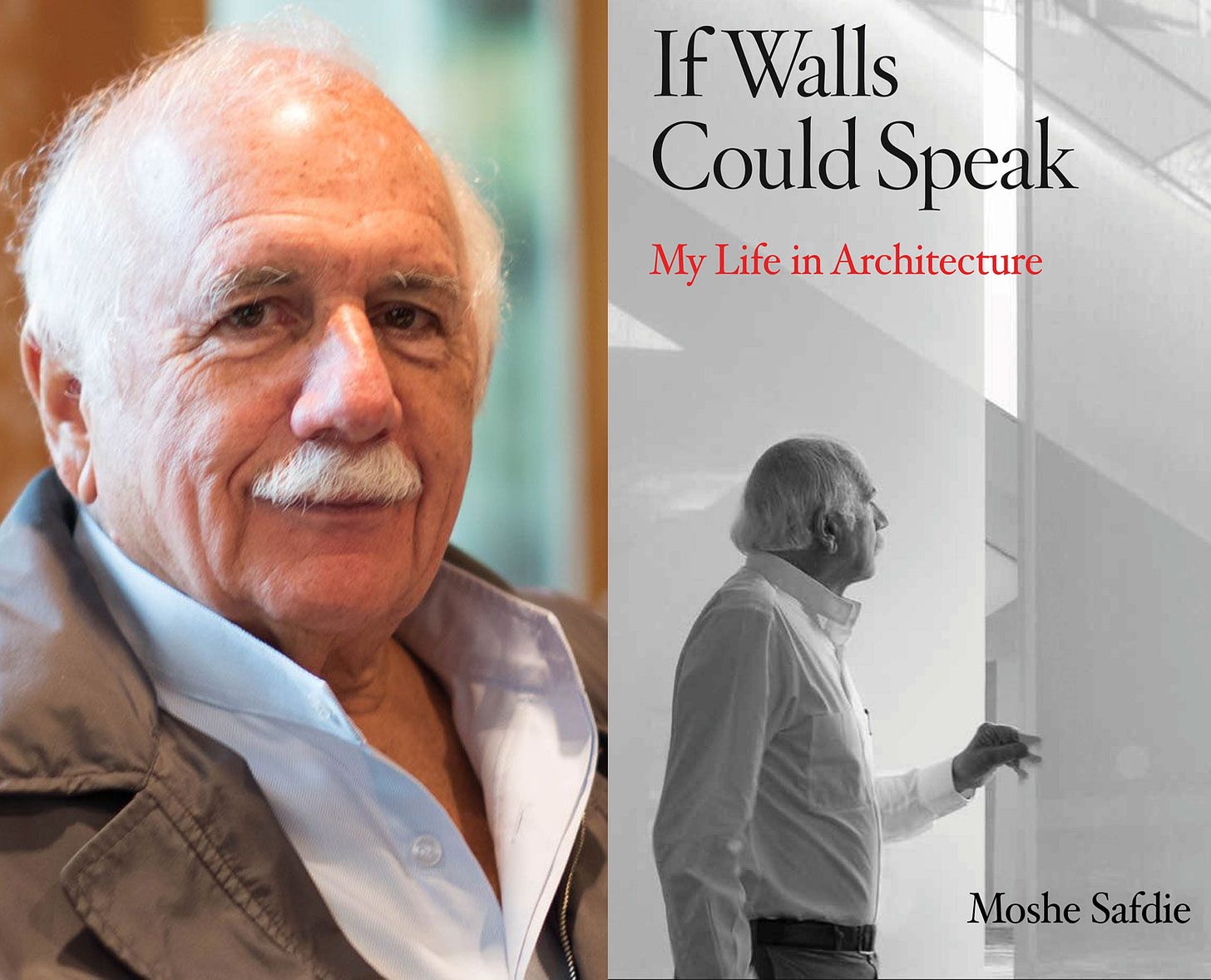

If Walls Could Speak: My Life in Architecture

Moshe Safdie

Atlantic Monthly Press, 368 pages, 2022

Moshe Safdie, the decorated and polymathic Israeli-Canadian-American architect and, more recently, the author of a superb memoir, designed two particular buildings of critical importance to my life—and to the lives of many others.

While Rosovsky Hall at Harvard-Radcliffe Hillel and Ben Gurion Airport’s Terminal 3 pale in comparison to Safdie’s more celebrated projects, like Singapore’s iconic Marina Bay Sands or the magnificent Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, they resonate strongly with Safdie’s greater mission.

Rosovsky, built the year before I began college, housed all Jewish communal functions at Harvard, where a pluralistic community of hundreds of Jews gathered daily and, especially, on the Sabbath for meals, classes, and services. The building’s curved, glass-enclosed structure ensured that Orthodox Jews worshiping in one room remained in eyeshot of Reform Jews praying in another, and its open courtyard anchored the entire structure. It was in Rosovsky that I served as president of this diverse, bumptious, but ultimately unified community and first laid eyes on the woman who would become my wife, later announcing our engagement in one of its soaring spaces.

Terminal 3, where, as an Israeli practicing American law, I have spent far more time than I care to admit, ascends, beckons, welcomes, and bids adieu all at once. Its centerpiece is what our family calls the “hello-goodbye corridor”: a high-ceilinged, naturally-lit pair of broad walkways, sloping gently downward in opposite directions and meeting midway at a fulcrum (imagine two parallel seesaws with opposite ends up and down). Departing travelers traverse the corridor from passport control to the central concourse, waving as they go by at arriving passengers making their way from their planes to the baggage carousel. The arrangement underscores the holistic nature of travel, of how everyone in the airport has come and gone and come back again.

Both Rosovsky and Terminal 3 reflect Safdie’s profound commitment to merging function and form, to making public spaces accessible and useful while elevating and inspiring them, to unifying their distinct pieces.

“Architecture,” Safdie writes in his highly readable and lavishly illustrated If Walls Could Speak, “does not exist on some abstract, ethereal plane where demigods wave their wands. It is grounded in actual places filled with actual people.” Over the course of nearly 60 years, he has labored assiduously to serving, creating, and uplifting communities through his extraordinary designs.

Born in 1938 in hilly Haifa in British Mandatory Palestine, Safdie came of age during Israel’s fight for independence. His earliest architectural experiences involved the contrast—still very much evident today—between the sleek, modernist downtown near the port, the vaulted, domed Arab villas of the lower city, and the Bauhaus-inflected buildings higher up the hill. Young Moshe decided that the ideal home

must have its own territory—well-defined and private, even if it small. It must always have a garden or courtyard or some other form of outdoor space—a transition zone, making a connection between the sheltered world indoors and the natural world outdoors.

He soon put this philosophy to work, enrolling at Montreal’s McGill University after his father, a merchant disillusioned by the nascent Israeli government’s oppressive socialism, decamped for Canada. Unlike most schools, which classified architecture under the rubric of the fine art, “architecture at McGill was part of the school of engineering, and deeply influenced by that central fact: architecture was about building, and building required technical expertise in many fields.”

Adopting this modernist approach, Safdei unapologetically rejected both traditionalism and postmodernism. The modernists insisted that architecture “provide housing for masses of people, not just the affluent” and regard cities “as a holistic environment, not just a locus of a few grand public buildings,” in Safdie’s estimation.

It must concern itself with infrastructure—things like transportation and utilities and other services—that encompass and improve society as a whole. All of this resonated with the values I had absorbed as a youth in Israel.

Safdie emerged into the public eye in 1967, not yet 30 years old, when his team won the design competition for that year’s Montreal Expo. Their widely acclaimed Habitat ’67 project comprised a series of pre-fabricated units suspended over one another, each with its own outdoor space, to create a sort of manufactured hilltop structure. The art critic Blake Gopnik, whose family was among the first to take up residence in Habitat, wrote that “every minute in the building felt unlike the next, as space, light, air, and sound danced around you. My parents built a jungle-gym on one of our terraces, but the building was the best climbing frame of all.” Habitat, variations of which Safdie would later re-create on multiple continents, catapulted him to critical and financial success.

Returning to his native Israel, Safdie helped redesign the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City, as well as the Mamilla neighborhood just outside its walls, a project that spanned more than three decades and has proved a smashing success. Mamilla has become a gorgeous gateway to the Old City, its terraces trickling down the biblical Valley of Hinnom, its combination of residences, hotels, and shopping representing, in Safdie’s words, “a rare example of a planned public space that performs as anticipated” and one of “the few places in Jerusalem where Arabs and Jews enjoy the city together.” Later, he would also redesign Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial and museum.

Scale posed a unique test for Safdie, as his projects ranged from the relatively modest, e.g., remodeling his own 18th-century colonial home and his three-story studio, to the middling, such as a courthouse in Springfield, Massachusetts or stunning museums in Ottawa and Kansas City, to the truly gargantuan, like the Marina Bay Sands resort, the Raffles City Chongking complex, or the Changi Airport in Singapore. “A world of 10 billion inhabitants [will] present unprecedented challenges,” he muses. “How can architecture promote individual well-being and a balance with nature in the age of megascale?” His own structures provide a helpful answer.

Along the way, Safdie recounts the many unusual experiences that punctuated his storied career, including taking part in designing the Israeli-made Merkavah tank, spending a night in jail in Berkeley during the People’s Park protests, riding in King Hussein’s helicopter with Yo-Yo Ma, debating the merits of angled crucifixes with the archbishop of Cartagena, Colombia, and encountering groupies in rural Saudi Arabia.

Among Safdie’s most endearing traits is his humility, and perhaps the most enduring lesson of his autobiography is its injunction to persist in the face of failure. Safdie notes that his firm has won only about 50 percent of the projects it has pitched, and many of those successes were scrapped before completion. If Walls Could Speak is strewn with the detritus of ambitious, failed endeavors, like a Columbus Circle megaplex far superior to the existing one, a half-built yeshiva in Jerusalem, and the National Museum of China. Then, too, Safdie struggled to clear obstacles posed by petty rivalries with other superstar architects, impossibly difficult clients (Sheldon Adelson prominently among them), and myopic zoning boards allied with NIMBYist locals.

“Given the range of imponderables,” including the legislative mandate that architectural firms provide—and adhere to—a fee estimate, Safdie posits that “architecture is a high-risk profession.” But “it is also a deeply satisfying one,” affecting “the way people work and sleep and travel; the way they consume the planet’s resources; the way they derive aspiration and inspiration from the built environment around them.” That satisfaction radiates from the pages of his memoir, which shimmers with the passion he imparted to all of his projects, big and small.

In the end, Safdie’s legendary career has been typified by the sense of community his spaces have fostered. “People,” he writes, “want entertainment and culture, libraries, civic facilities—all of which also bring everyone into contact with a greater variety of human life and social backgrounds. People want a sense that they are part of a larger communal identity.” As he approaches his 90th birthday, Safdie can justifiably take pride in achieving his lifelong mission.

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.