Children Were Robbed of an Entire Year—Why Won't We Hold the Thieves Responsible?

A review of "The Stolen Year: How COVID Changed Children’s Lives, and Where We Go Now" by Anya Kamenetz

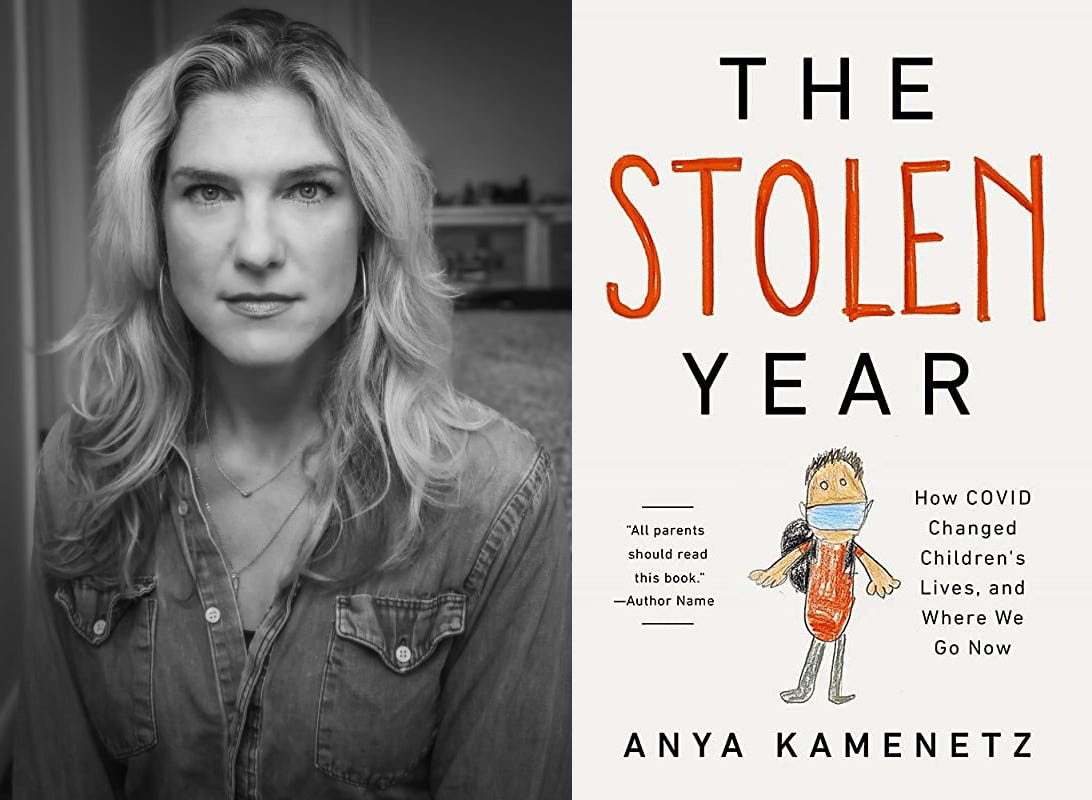

The Stolen Year: How COVID Changed Children’s Lives, and Where We Go Now

Anya Kamenetz

PublicAffairs, 352 pages, 2022

Three years into the Covid era, we suffer from a passive voice problem. The true sin of passive sentences isn’t wordiness or lack of precision, but evasion: they offer a way to hint at a problem but back off at the last second, never quite taking a stand, never quite risking being wrong—or being thought wrong.

The passive voice problem, in its purest form, is a cliché, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t real. It’s the difference between the person who says, “Mistakes were made,” and the one who says, “I screwed up, and here’s how.” One is specific, honest, and reflective; the other evades responsibility and introspection while signaling that the next thousand words will say as little as humanly possible.

We’re all guilty of the passive voice problem, of course—and, mostly, in less deliberate ways than that example. It’s part of being human. But that doesn’t mean we should surrender to it.

The passive-voice problem can strike even the well-intended. I want to believe that’s what happened with Anya Kamenetz. To give her credit where it’s due, she sees—and saw, early on—the very real problems with how America treated its children during 2020 and 2021. Too often, children were afterthoughts, asked to sacrifice (or to have their childhood sacrificed) for the vague, impulse-driven comfort of others. Children were isolated, hampering social and emotional development. School closures led to learning loss, particularly among lower-income, black, and Latino families—but also to the loss of social services that schools provide beyond education. Our policy-level responses to Covid—in particular, shutting the doors of public schools for, on average, more than a year—caused specific, concrete harms to children. These losses varied from child to child, depending on their circumstances, but a good rule-of-thumb might be: the more vulnerable a child was, the more our policy decisions harmed that child. In The Stolen Year: How COVID Changed Children’s Lives, and Where We Go Now, she seeks, stridently, to persuade her fellow progressives to set aside the partisan logic of the Trump era and to acknowledge the need for repair along with her.

But Kamenetz, too, suffers from the passive-voice problem. She can’t bring herself to acknowledge whom this account holds responsible: liberal and progressive political leaders, public health and education experts, and the very voters she seeks to persuade. A year of children’s lives was stolen—but the thieves go unnamed.

Kamenetz is an education reporter for NPR, but The Stolen Year isn’t really a work of reporting. Her goal is not to provide an account, or an accounting, of that first pandemic year, but to convince her readers that three things are true: First, that Covid stole childhood from children, especially (though not exclusively) through school closures. Second, that public schools aren’t merely important, but are, in fact, the most important part of the United States’ welfare system. Third, that the ways to repair the damage done in 2020 and 2021—or to prevent its recurrence—point toward a long list of progressive policy goals, from increased spending on public school and childcare to large-scale reforms of welfare programs, the health care system, immigration law, and environmental policy.

It’s convenient that the solutions map so neatly onto what progressives already call for. I realize, of course, that Kamenetz doesn’t write for me: I’m not a progressive and, even if I were, I wouldn’t need to be persuaded that Covid school closures were a deeply misguided policy. But if she’d ended by simply listing a series of choice-oriented education reforms to which I’d be more instinctively amenable, I’d still be wary. If all that Covid has shown you is that your team has (and always had) all the right answers, then you’re almost certainly doing it wrong. Regardless of intention, this is the kind of thinking that only continues the political weaponization of children.

That brings us back to the passive-voice problem. Mistakes were made, Kamenetz urges her fellow progressives to concede. But which mistakes? By whom? It’s far easier to land on solutions which fit easily within what you’d otherwise desire, had there been no Covid-19, no school closures, no learning loss—whatever your heart longed for in December 2019—when you don’t address questions of responsibility. They’d lead you, potentially, to uncomfortable truths, or to places where policies you’re amenable to failed, or simply to the facts and details that, like stray pebbles on the infield dirt, can transform the routine play to catastrophic error.

So Kamenetz largely avoids her primary contention, that closing schools for in-person learning during the 2020-2021 school year was the central error of child policy, one that unnecessarily removed the most important cog of America’s welfare system, injuring the most vulnerable disproportionately. Only one of the book’s 11 chapters—the eighth—discusses this policy error and its aftermath in detail. Indeed, The Stolen Year struggles to keep its focus on the Covid era: a little more than half actually discusses anything from 2020 on. The rest is a simplified, politically-conditioned history of American public schools, child protective services, and social welfare programs. Kamenetz offers an account that blames historic racism, sexism, and xenophobia for the policy errors of 2020-2021 more than those who called for school closures or the leaders who enacted and then refused to end them: “The decisions that led us here,” she contends, “were made by powerful adults over centuries.”

Maybe it’s an effective rhetorical strategy to tell readers that the legacy of slavery was as much to blame for the damage done by school closures as were the progressive school boards, union leaders, mayors, and governors who decided to close schools and then declined to reopen them. It’s easier, after all, to concede the error if there’s no one, really, to blame.

But that’s not exactly Kamenetz’s contention. “All of this was not inevitable,” she declares early on, quoting an interviewee: “it was ‘super fucking evitable.’” The recognition that school policies were chosen and the refusal to blame those who made those choices is the fundamental contradiction at the heart of The Stolen Year. Those she chooses to hold responsible are long-dead ancestors whose bigotry set us on tracks leading to Covid disasters—or, among the living, easily-predicted boogiemen.

For example, in an early chapter, Kamenetz observes that Covid-era school policies—not just closures, but also de-emphasizing grades and evaluating student work—meant that “the social contract of school was broken.” And it’s not that we went into this blind: “In March 2020, in the United States, people in power knew, or should have known, that keeping schools closed for even a few weeks would have serious, long-term, inequitable consequences.” American Covid closures, she notes, “stood out globally”: for the most part, American classrooms were closed for over a year; in European and Asian countries, the length was far, far shorter.

These are statements that, she correctly notes, were controversial to say aloud during 2020 and 2021. Indeed, they became near-heresies if you valued your status in good-standing as an anti-Trump progressive. And yet, in the same chapter from which I’ve been quoting, Grover Norquist comes in for greater criticism than those who actually decided school policy. Kamenetz’s villains are familiar and predictable: Donald Trump and Betsy DeVos are Public Enemies No. 1 & 2. School-choice advocates like Corey DeAngelis—a vociferous critic of public school closures during 2020 and 2021—also make sinister cameos.

Each chapter begins with an epigraph from Donald Trump: some obnoxious, bloviating line that has something to do with Covid, but isn’t really related to schools. The purpose is obvious. Kamenetz worries that it is still heretical to point out that prolonged school closures were a disastrous policy choice that sacrificed American children in order to ease the unfounded anxieties of the adults who should have known better. So she must remind her readers that, like a good progressive, she too blames Donald Trump above all others.

It’s not unfair to say that Trump helped cause prolonged school closures—just not for the reasons Kamenetz implies. It was, in fact, his support for in-person schooling beginning in the summer of 2020 that polarized the issue and made it politically toxic on the left.

Take the case of the American Academy of Pediatrics school guidance leading up to the 2020-2021 school year. In late June, the AAP called for a return to in-person classes in the fall, emphasizing the negative educational, developmental, and psychological consequences of continued remote school. The following week, Trump and administration officials began to cite the AAP report in calls for schools to reopen for in-person learning in the fall. On July 10, the AAP issued a joint statement with the nation’s two largest teacher’s unions walking back the earlier guidance. From here, there was no turning back: the issue had been touched by Trump.

But that second AAP statement also points us toward those who should be held responsible. School re-openings, it insisted, should be made by public health agencies, school administrators, and local officials. Indeed, this is largely what we got: a hodge-podge of policies determined along partisan lines. The deeper blue your school district, the more likely you were to remain out of the building; the redder, the more likely to be in-person.

Kamenetz hints, at times, that these leaders may have made mistakes. In spring 2020, she reports, unions in Los Angeles County negotiated “just a twenty-hour workweek for remote teaching.” But she stops short of casting blame, just as she does, later, when examining union resistance to re-opening schools throughout the 2020-2021 school year. It’s more important to note that conservatives blamed them too much than to measure precisely how much blame they deserve.

The book’s very structure allows Kamenetz to stop short of assigning responsibility. Individual chapters are broken into short sections and subsections—nothing unusual for a work of contemporary nonfiction. But these sections are largely less than a page long, often only one or two paragraphs, and the jumps allow Kamenetz to consistently avoid the implications of her claims and instead redirect—sometimes to the past, sometimes to another example, sometimes just to a new heading that makes claims unsupported by the actual text and reported evidence.

Consider this example, drawn from that lone chapter on school closures in 2020-2021. Here’s the section, in its entirety, under the sub-head, “Health Authorities Recommended Opening Schools in the Fall”:

In the spring of 2020, schools were closed out of caution. It was relatively uncontroversial. It happened almost everywhere in the world—although European countries started opening up within several weeks, and Sweden’s never closed.

The 2020-2021 school year, the subject of this chapter, was a whole different animal. Our peer countries committed to opening schools whenever possible. Politics held sway over science in the United States’ weak, decentralized, inequitably funded school system.

Beyond brevity, you’ll notice a few things. For instance, the text itself provides no evidence for the sub-head’s claim. The section title makes an assertion requiring support—followed by tangentially-related text that provides relatively uncontroversial background facts. It ignores the fact that American health authorities were markedly less supportive of in-person schooling in 2020, 2021, and even 2022 than their European counterparts. Take, for example, the CDC’s February 2021 revisions to its school reopening guidelines (issued far too late to affect the 2020-2021 school year). Framed as a plan to prioritize in-person learning, they nonetheless recommended that the 90 percent of American middle and high schools then in “High” transmission areas stay remote indefinitely, rather than return to the classroom. Elementary schools received a slightly different guidance: to employ reduced attendance or hybrid learning, modes that (as Kamenetz elsewhere observes) were linked to worse learning outcomes than fully-remote classes.

Kamenetz knows the facts I’ve offered in the previous paragraph; she co-authored the article I’ve linked to as a source. But pushing forward, making connections, assigning blame—all this would require alienating those she wants to persuade. It would require admitting that her own political allies were, largely, wrong on this issue. She would need to cast blame not only on Donald Trump and Betsy DeVos, whose responses were indeed deeply flawed, but also at union leaders and the relatively anonymous local politicians and school board members in deep-blue college towns and majority-minority urban districts—and, of course, on nationally-recognized figures including Anthony Fauci, Andrew Cuomo, Gretchen Whitmer, Kathy Hochul, Phil Murphy, and Gavin Newsom. They were, to borrow a phrase from Bush 43, “the deciders.” They decided poorly.

It would also mean admitting who chose correctly. Sometimes progressives: Bill DeBlasio’s resistance to closing schools in March 2020 looked, by that fall, deeply prescient. But it would also mean conceding that those who chose to open schools or advocated for them were correct, despite the (R) frequently attached to their names: Ron DeSantis, Brian Kemp, and other red state governors; the activists for in-person schooling she dismisses as “angry mobs of anti-maskers, anti-vaxxers, ant those opposed to schools teaching about racism and LGBTQ rights.” Tellingly, when comparing conditions in Florida and California schools, Kamenetz goes out of her way to avoid using DeSantis’s name; what readers need to know about this nameless figure is not his advocacy for the in-person classes she praises, but his opposition to school mask mandates.

Admitting all this would mean saying: “You, my political allies—you and your heroes, dear readers, were wrong; our opponents were right more often than we were, at least on this issue. Our choices had consequences that hurt children, and we should reflect on the way negative partisanship led us to set aside our true convictions for over a year.”

That probably wouldn’t be very persuasive. But at least it would be honest.