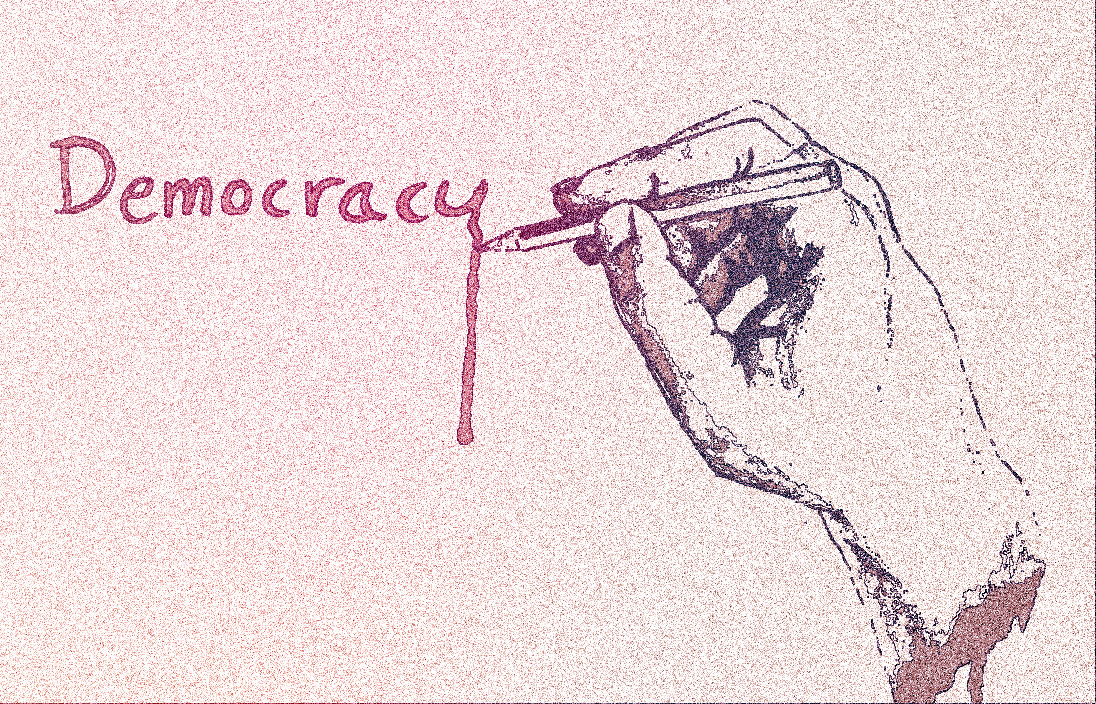

Democracy Dies of Disordered Desire

Socrates, the American Founders, and the plague of factionism

At some point in their educational journey, every American child learns that democracy first appeared in ancient Athens. If by chance they also hear of Socrates, whether from a teacher, a textbook, or (God-willing) a Platonic dialogue, it’s likely to inform them that the city of Athens executed him for his beliefs.

Probably very few American school-children ever entertain the disquieting fact that it was the first democracy who murdered the father of philosophy.

That fact was not, however, lost on Socrates’s students.

While neither lived to see the last gasp of democracy in their city, both Plato and his student Aristotle maintained that rule by the demos, the people, tended to devolve into tyranny. Neither saw democracy as the best or most just form of government. Rather, Plato thought that democracy, powered by an insatiable desire for freedom, would ultimately overturn itself: “they end up … by paying no attention to the laws, written or unwritten, in order that they may avoid having any master at all.” It was perhaps inevitable, in the end, that a political arrangement at least partially responsible for Socrates’s tragic demise would be seen as seriously flawed by Plato and Aristotle.

Some historians think that the charges leveled against Socrates in the last months of the 5th century were religiously motivated. Others argue that his philosophizing led committed anti-oligarchs to target him because they feared the Spartans had him in their pocket. Athens’s great rival had already defeated them in war. Now, Athenian democrats worried, that fearful city was meddling in their internal politics. In such an environment, the risk of disloyalty to democracy was too great to allow Socrates to continue to speak freely. But he refused to rein in his tongue or his reason. He had dedicated his life to philosophy, and he felt giving it up would amount to betrayal. Despite a relatively close vote at his trial, the end result may have been a foregone conclusion.

From this temporal distance, the political path to Socrates’s death and the lessons it offers take on an evergreen quality. It can teach our age much about how democracies go off the rails.

Like American democracy today, Athens had been through a turbulent period immediately before Socrates’s trial for impiety and corrupting the minds of the youth. A pro-Spartan oligarchy known as the Thirty Tyrants had been installed only four years before, violating many of the city’s most dearly held traditions. In such a situation, their ouster was predicable enough, and the Athenians carried it out within a matter of months. But among the city’s democrats, longstanding resentments toward and fear of the rising Spartan power across the Greek peninsula became the occasion for recriminations and deepening suspicion. For this reason, some historians have suggested that the brief tenure of the Thirty Tyrants played a role in the fall of Athenian democracy more than 75 years later.

America, the world’s oldest democracy, has not suffered such a tyrannical takeover in recent years, but not a few people blame one or the other party for trying. Democrats sometimes suspect that they have the corner on democracy, whereas Republicans often speak as if their tribe are the only real Americans. Both, like their ancient Greek forebearers, have become terrified of disloyalty. Both, like the ancient Athenians, fear the machinations of foreign powers: Russian hackers unsettle the left, Chinese geopolitical power spook the right. Also, like Socrates’s political enemies, many on both sides of the aisle are clearly willing to sacrifice other people’s reputations, livelihoods, and well-being to ensure that “their” America survives.

In this environment, some people, especially Republicans, have started arguing that political violence is understandable, even morally permissible. Rachel Kleinfeld of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace found that the 2020 election was “an inflection point.” By February of 2021, 20 percent of Republicans and 13 percent of Democrats thought violence justifiable. A full quarter of Republicans in the study said the same thing about threatening Democratic political leaders. Kleinfled noted that these numbers approach those recorded among Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland at the height of the troubles. If Donald Trump is the Republican nominee in 2024, you could bet the farm those percentages will continue to rise.

Now, imagine for a moment Socrates suddenly stepping out of the past and plunging into the tumult of American politics. Often enough you would find him playing the gadfly on Twitter, Fox News, or our university campuses. Still more often you could find Christian nationalists and progressives saying, “that irresponsible philosopher will destroy the country” or “if his ideas win out, The Handmaid’s Tale will seem mild!” or “if only someone would debate him and stand up for truth!”

Doubt a grand Socratic entrance onto the American stage would illicit this sort of reaction? Read Plato’s Republic. There we find Socrates advocating for a communist political polity in which big brother lies to the populace for their own good. Men “possess” women, who are nevertheless said to be equal and then mostly denied sexual freedom. Infanticide gets legislated for children born in circumstances of which the city disapproves. Even if we believe that in writing The Republic Plato put much of his own political theory in the mouth of his teacher, these ideas had to at least make sense coming out of Socrates’s mouth. The gadfly must have believed some unsettling things about politics.

Thus it would come about that supporters of either of our major parties might try to assassinate him—or, if that proved impossible, begin working to cancel or de-person him online. Like what happened in ancient Athens, many would feel he had destabilized their political position, played into their opponents’ hands—in a word, that he posed a clear and present danger to their felt identities and ways of life. Then would come the moment everyone had waited for: the slick-talking, toga-sporting provocateur would get his comeuppance. Someone digs up old tweets he sent as a teenager. A former coworker claims he suggestively put his hand on her lower back without consent. Tucker Carlson devotes an entire show to the undeniable fact that Socrates is a communist and that he is bringing up a generation of students to hate America. Or CNN runs a piece on their front page with the thesis that, contrary to his reputation for gender equality, Socrates actually wants to reverse the sexual revolution and confine the vast majority of women to the home.

Worse denouements can hardly be ruled out for an American version of history’s most famous gadfly. Someone places a pipe bomb in a postmarked package outside his door, guns him down as he makes for the exit after a public lecture, or, perhaps, slips silently through his entourage on the street and punctures his lungs with a single thrust of a knife. Arrests occur, the attacker’s book-length manifesto is commented upon, partisan luminaries issue celebratory tweets about the philosopher’s death, and those tweets are scolded by some and deemed understandable but ill-advised by others.

Then the news cycle moves on. Our culture war continues as before, veering ever closer to open violence. Few Americans would have any sense that something irreplaceable had died along with the threat to their sense of identity.

This tragedy and real-world tragedies like it occur because of factions. Both the ancient Greek philosophers and many of the American Founders said as much, and they thought democracies particularly vulnerable to them. “The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice,” James Madison wrote in “Federalist 10.”

The instability, injustice, and confusion introduced into the public councils, have, in truth, been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have everywhere perished.

Plato did him one better:

Too much freedom seems to change into nothing but too much slavery, both for private man and city.

For both Plato and Madison, “too much freedom” became a problem when one part of the populace began to judge that they are owed more and more and consequently feel less and less obligated to their fellow citizens.

Citizens really are owed a real and not merely nominal ability to vote. Take away enfranchisement, and you sever the root of democracy. The same goes for a social and governmental commitment to generally agreed upon human rights.

But (and I write this with some trepidation) it is possible to feel ourselves owed too much, to be driven politically by a lust for more. In a democratic society like the United States that reveres freedom and individualism, the ever-expanding list of freedoms I believe I possess can and will eventually conflict with someone else’s list. Worse, whole subcultures and identity groups that feel themselves deprived of something necessary for full American-style freedom will eventually feel themselves the victims of social injustice when others receive what they feel they are owed. This is the mainspring of factionalism.

To be sure, factions are an inevitable part of life in a democracy. Both Plato and Madison conceded as much. But they arise more readily and hold to their claims with more ferocity in societies where citizens feel themselves owed more. If trust between factions is broken, and it frequently is, seeing one’s way through the impenetrable gloom of mutual mistrust and the knotted difficulties of the original dispute to political compromise can quickly become impossible. Politics devolves into a zero-sum game. Either my group wins or yours does.

This, Plato thought, is how democracies become tyrannies. In each faction, fear mounts of what its rivals, the others, will do next. What they need, many begin to argue, is a strong hand at the tiller, someone who will stand up for people like us. This figure is waiting in the wings. “I’m the only one who can protect you,” he says. Plato refers to this man as “the people’s defender” presumably because that it how he bills himself. Yet he writes that the tyrant’s soul is disordered, ruled by what older writers called lust, uncontrolled desire, “and while not having control of himself attempts to rule others.”

“Then,” Plato has Socrates say,

the tyrant must gradually do away with all of [his helpers], if he’s going to rule, until he has left neither friend nor enemy of any worth whatsoever…[T]here is a necessity for him, whether he wants to or not, to be an enemy of all of them and plot against them until he purges the city.

But this purge is “the opposite of the one the doctors give to bodies. For they take off the worst and leave the best, while he does the opposite.”

The only way to avoid this fate, Plato and the American Founders believed, is through moral and civic education, what in the Founders’ generation were called Republican virtues. It would mean devoting ourselves to the belief that we have responsibilities that we must fulfill toward our neighbors and fellow citizens even if we consider them enemies. Agreeing among ourselves what those responsibilities are requires at minimum some common vision, a bare-bones set of commitments about what living well together means. It requires, in other words, ordering our desires toward a common vision of the good.

Such a revival, which requires recalling that all education is inevitably moral, seems unlikely at this hour. But if we cannot bring it about, our American Socrates would be left with only one productive question to ask us: “Will the tyrant appear in the footlights from stage left or stage right?”