Everything Goes and Nothing Matters

A review of "Philip Roth: The Biography" by Blake Bailey

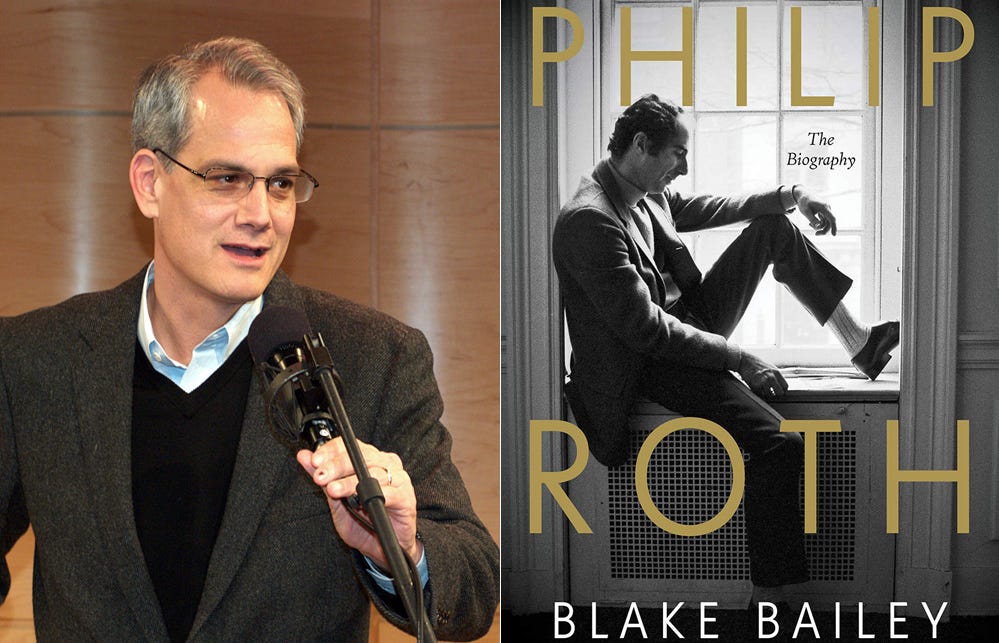

Philip Roth: The Biography

Blake Bailey

W. W. Norton, 912 pages, 2021

By 1972, Philip Roth was free. Free from the hell of his first marriage, free to enjoy the fame and financial windfall of Portnoy’s Complaint, and “free” in his writing, the term he used when the words were flowing. Roth “had his old mojo back,” Blake Bailey declares in his biography, before correcting himself in the same sentence: “or anyway was having fun again.”

Roth was writing plenty, but little that was any good: the lesser comedies of Our Gang and The Great American Novel, followed by the grasping (but more ambitious) novella The Breast and My Life as a Man, a novel about his inability to write a novel about the only subject that seemed to matter: that he had been tricked into marriage with a woman he loathed.

Not yet 40, Roth had become one of America’s best-known novelists. Yet his career was in crisis. What to do with this enormous talent, this even greater work ethic? After Portnoy, what taboos still remained? What was at stake in any of it?

That April, two events followed quickly on each other that transformed Roth from a minor novelist who couldn’t make good on his potential to a major American literary figure: he purchased the Berkshires cottage where he would pace and write for the next 40 years and, in order to close on it, canceled a six-week vacation in Japan.

Instead, he went to Prague.

The city seized him and, if it didn’t quite change Roth, changed the questions that drove him. In Czechoslovakia, the literary vocation of the writers he met couldn’t differ more from his own. In “my own free country,” he would look back and write in 1982, “it seemed to me then, ‘everything goes and nothing matters,’” while in “totalitarian” Prague, “nothing goes and everything matters.”

Or, as he explained to the Czech exile Tony Liehm, whom he befriended on his return the U.S.:

I’ve just published a pamphlet against Nixon [Our Gang]. … It’s selling like hotcakes, and all that can happen to me is that I’ll get a little richer. While, with you, writers that do about the same thing can count on going to prison. And I have this need to understand why they do it.

The second half of Roth’s career, at its best, became an examination of how one lives, let alone writes, in a country where everything goes and nothing matters.

The quartet of short novels from the late 1970s and early 1980s that are centered on his most famous literary alter-ego, Nathan Zuckerman, are in large part about the failures of literature in free countries. Zuckerman can write, and write, and write—can achieve wealth, fame, and notoriety from his Portnoy-like bestseller, Carnovsky—but his literary career pales in comparison with that of Anne Frank’s one volume: nothing matters. In The Ghost Writer (1979), the quartet begins with Zuckerman’s attempt to imagine Frank’s career had she lived, and, in The Prague Orgy (1985), ends with Zuckerman attempting (and failing) to smuggle the unpublished stories of a Yiddish writer killed by Nazis out of Prague. Everything, finally, seems to matter in this act—but, of course, nothing can go.

Roth soon found a parallel to Prague in Israel, a place where the stakes were higher in both life and art. The country would shape his fifth Zuckerman novel, The Counterlife, and the subsequent Operation Shylock (narrated by a fictional Philip Roth), contrasting it, in shifting, contradictory narratives, with the U.S. and U.K. But in Israel, there was too much meaning, perhaps: a land of doubles, caught in an eternal version of Jacob dream-wrestling with a man who might be an angel, might be God, or might be another version of himself.

And then Roth rediscovered Newark. “During the eighties,” Bailey writes, “when visiting his father, Roth would detour through Weequahic [his childhood neighborhood] and gape at the desolation—wondering of course, what to make of it in his fiction. ‘Newark was Prague,’ he said. ‘Newark was the West Bank … a place that had a great historical fall’”: the subject of his acclaimed American Trilogy, in which the writing life matters—not again, but finally.

Where to find meaning in a country where you can write whatever you want, where there are no taboos and no jailed dissidents? Roth’s first answer appears in his 1989 eulogy for his father:

His sense of loyalty was monumental. … He loved his loved ones as doggedly as he did everything. But he was a fighter as well and fighters don’t endure on love alone. He knew how to hate, and who to hate, and was not shy about letting you know the score. He simply did not understand what it meant to quit or to back away or to give in.

In the right balance, the result of this intense commitment is “a solid man … an honest man”: words that could be applied to Swede Levov, Ira Ringold, Coleman Silk, or the Herman Roth of The Plot Against America—all men driven to crisis by their commitment to family, friends, city, cause, or vocation. In the struggle to remain honest to one’s loyalties while blindsided, again and again by fate, Roth found the great dramas of postwar America.

On the flip side, there’s Mickey Sabbath, Roth’s fullest and least restrained exploration of pettiness and hatred, his deepest mining of the repellent. “I have chosen to make art of my vices rather than what I take to be my virtues,” he said to his friend, the religion scholar Jack Miles, of Sabbath’s Theater. And, indeed, Roth might as well have been describing himself as his father in his eulogy: both his sense of loyalty and his capacity for hatred were monumental.

Bailey shows a Roth who could be selfless and munificent: arranging for the publication of East European writers through the Writers from the Other Europe series; channeling money to Czech literary dissidents and nearly being arrested by Soviet police in the process; the checks for $25,000 or more to friends in need that flow breezily throughout the biography. And, of course, Newark: after Roth’s death, the largest portion of his estate (and his personal library) went to the Newark Public Library, a gift of loyalty to an institution that once nourished him—and, Bailey implies, driven by Roth’s ability to hold on to grievances. In this case, his indignation, still lingering after half a century, at the City Council’s 1969 decision to cut library funding after the Newark Riots.

If only all Roth’s grievances were as high-minded. The flip side of Roth’s loyalty was a thin-skinned pettiness that often grew to hatred: of critics, of past lovers, of former friends, of near-strangers. Score settling abounds—in Roth’s life, his fiction, and in Bailey’s biography.

This even shapes Roth’s decision to authorize the biography itself. “I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting,” he told Bailey, lines offered as an epigraph in an effort to announce that this will not be an apologia, despite the involvement of Roth and his estate. But careful readers will also be struck when Bailey quotes Gore Vidal’s blurb for Claire Bloom’s biting memoir, Leaving A Doll’s House: “she even makes—inadvertently—her last husband, Philip Roth, into something he himself has failed to do—not for want of trying—interesting at last.”

Roth got Vidal (and Bloom, and Bloom’s daughter from an earlier marriage) in I Married A Communist—but it’s easy to imagine Bailey writing with a handful of other, smaller targets in mind. Indeed, he comes across almost as obsessed with some of Roth’s detractors as the novelist himself. It’s unclear, after all, why we need to hear, repeatedly, that New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani disliked Roth’s novels except that it pissed off Roth—and still pisses off Bailey. Roth, one gets the sense, wasn’t satisfied with universal acclaim: it needed to be unanimous. Bailey chooses to treat this not as an aspect of his subject’s character but as a bloody banner to wave on his behalf.

This twining of love and hate, of intense loyalty and intense pettiness, suggests a way to think about Roth’s two disastrous marriages: he needed, simultaneously, someone whom loyalty demanded he rescue—and also needed someone to hate. Maybe this is also a way to approach the charge of misogyny in his life and his work. About these, we might say: “He could love a woman as doggedly as he did everything; but he also knew how to hate, and who to hate, and was not shy about letting you know the score.” Or, as he observes in Operation Shylock, “There he was. And wasn’t.”

“The meaning of life is that it stops,” Roth repeated often in his declining years. Everything goes, Roth came to realize, for now. But some day, it will end. And that matters too.

Roth’s awareness of mortality—some close to him felt, at times, it was an obsession—developed during the same period in which he first tried to make written sense of his Prague epiphanies. His mother died of a heart attack in 1981; the next year, the otherwise hale, 49-year-old Roth was diagnosed with significant coronary artery disease; an emergency bypass surgery would follow in 1987.

And then there was the back pain. In 1955, on his last day of basic training at Fort Dix, Roth suffered a spine injury that lingered for the rest of his life: beginning in the 1960s, he often needed to wear back and neck braces.

The pain rose to a crisis in the 1980s and 1990s: his pain medications induced hallucinations and depression, but without them, the strain of his back itself was enough to induce thoughts of suicide. Still dealing with the mental toll of his collapsing marriage to Bloom, Roth appeared ready to jump from the top of a residential tower onto Lake Shore Drive in 1993—at which point his brother and two friends convinced him to commit himself to a psychiatric hospital. The crisis passed, but Roth’s back pain (and the suicidal ideation it induced) would continue to linger for the rest of his life.

Mortality shadows all Roth’s fiction beginning at this time: graveyard and deathbed scenes, the Holocaust’s shadow, the loss of sexual vitality. Where Roth, the person, at times seemed terrified by the prospect of death and decline, as a writer, he stared at it unflinchingly—even as his literary powers diminished. Roth’s last five books are all determined confrontations with mortality. He grouped four of them together as Nemeses: that is, attempts to understand death as life’s true antagonist.

The meaning of life is that it stops: if that’s the case, then it’s hard to assess the meaning of a writer’s career except posthumously. Roth nonetheless tried to set his afterlife in the direction he wanted: announcing his retirement from fiction, his active role in the Library of America editions of his work, his selection of Bailey as his biographer, his orders to destroy most of his private papers after the book’s publication.

So Bailey’s Philip Roth has become a strange coda to Philip Roth, one that almost feels over-determined.

Published on April 6 to wide acclaim—by many accounts, the most anticipated literary event of the year—barely two weeks later it had been pulled by its publisher, W. W. Norton. On April 18, the first allegations against Bailey emerged; their number soon grew as more of his former students accused him of sexual harassment and assault. By April 21, he’d been dropped by his agent and Norton had suspended shipping and publicity. A week later, Norton took it out of print: that had been more than enough time for contemporaneous evidence—in Bailey’s handwriting, from his email address—to emerge. (Skyhorse Publishing—which also took on Woody Allen’s memoir after Hachette dropped it—announced in May that it had acquired the paperback, ebook, and audiobook rights.)

From one angle, it’s a plot Roth himself might have used: a writer’s magnum opus pulled from publication after allegations of sexual misconduct and assault. Yet the difference between Bailey’s life and a Roth novel is as simple as it is disturbing: Bailey has been accused of grooming and harassing eighth-graders (some as young as 12) and, in one instance, of raping a former student, then 22. Whatever sins Roth and his stand-ins have been accused of, these are not among them.

Given Roth’s own ambivalence toward biography, he might have been bemused, even briefly entertained by life playing a final joke on him. You can hear him quip, again, from beyond the grave: “Norman Mailer could only dream of such disapproval as I continue to arouse without lifting a finger.”

More likely, he’d have been Lear-like in his rage at both Bailey and Bailey’s accusers. Having spent a lifetime accused of misogyny, his defense—“Make me interesting”—now silenced by those who already hated him. The central injustice here was against him, he might have thundered, punished now for someone else’s misogyny.

If there’s any advantage to the mess that’s engulfed Bailey’s book, it’s that it offers readers a chance to think about the purposes of literary biography. Such works are important academic tools—and Philip Roth will be discreetly retained in university libraries for precisely this reason. They’re also opportunities for literary analysis: guidebooks between the life and the words, a task at which Bailey sometimes succeeds. Only sometimes, because he more often errs on the side of the third, least reputable purpose of the genre: gossip. So we read page after page about Roth’s sex life (well beyond the point at which it’s helpful for understanding the author of Portnoy and Sabbath’s Theater), but find no discussion of why Kafka mattered so much to him, or when he first read Henry James.

There’s a final purpose to literary biography, properly done: encouragement to read its subject’s works. Bailey’s biography, both when it succeeds and when it fails, makes one want to put down Philip Roth and go read (or re-read) Philip Roth. In the end, the novels are far more interesting than their author. And that’s how it should be.