How the Chinese Communist Party Can Bring America Together

Our intra-American debates matter. Still, we should remember that China is working tirelessly to establish a new world order where the entire notion of human rights is inverted.

From the start of his candidacy, President Joe Biden made “unity” a central feature of his pitch to the American people. Thus far it seems to have had little effect. As of late April, Biden was polling in the mere single digits with Republicans, resulting in the third lowest approval rating 100 days into any presidency in the past 70 years.

Biden’s speech to Congress marking his first 100 days in office seemed to convey an implicit awareness of this disconnect, and embedded within it were some promising signs of a plausible path forward. Writers such as Andrew Sullivan correctly underscored the importance of the overarching theme: American jobs are in, offshoring is out. But even more significant was Biden’s decision to identify the primary benefactor of post-Reagan America’s pro-globalization consensus: China.

Tying his “FDR-like” stimulus package to the great-power struggle between China and the United States was a smart move on Biden’s part. The deleterious effects of globalization on the American working class are inseparable from how it has simultaneously aided China’s rise. According to one study, China’s admittance to the World Trade Organization in 2001 precipitated the destruction of 2-2.4 million net jobs in American manufacturing and manufacturing-related industries from 1999-2011. In 2010, China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest manufacturer, and still holds that position comfortably today.

An increasingly nationalistic Republican Party, whose base now includes an outsized share of manufacturing workers who lost their jobs to China, should find much to like in an ambitious plan that hopes to counter China, in significant part by resurrecting American manufacturing.

Yet economics is just one of many issues in American politics, and it’s also one of the least divisive. With evidence of growing support for populist economic policies in the electorates of both parties, there’s little reason to think that higher taxes on the rich and more jobs programs will do much to improve the political balkanization Americans are experiencing. As Shadi Hamid has observed, the political debate in America has become less about ordinary political questions, and is now increasingly rooted in “foundational questions”—chief among them being: What does it mean to be an American?

Unity, and even long-term social stability, will only be achieved if Americans are able to find common ground on the foundational questions that concern our most deeply-held values, the questions that fall into the broad category of human rights. The most fertile opportunity for reifying our common identity as Americans comes to us in the form of China’s ruling party, the Chinese Communist Party, which represents an existential threat to the rights and freedoms we think a world superpower should strive to protect.

China has the most abysmal human rights record of any regime in the world today. Even when we exclude the era of Mao Zedong—who during his 27 years leading the PRC as Chairman (1949-1976) probably became the most murderous man in human history—the list of the CCP’s human rights violations is unparalleled, ranging from imprisoning a record number of journalists to systemic forced labor and organ harvesting of dissidents, and, most recently, the ongoing genocide of the Uyghurs in China’s far-western Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, also known as East Turkestan.

The outbreak of Covid-19, and the CCP’s fastidious efforts to cover it up as it spread around the world, provided a stark example of how China’s violations of human rights end up affecting us all. A growing majority of Americans now view the Chinese government in a negative light. This includes Congress as well, where there has been substantial bipartisan support for legislation that counters China’s human rights violations.

What has been less common, however, is a drawing of the contrasts between human rights in China and human rights in the United States, and to use this comparison to help us contextualize the domestic debate over human rights that is threatening to tear America apart.

For many critics of America’s record on human rights, there is an instinct to look at our country in a vacuum, to compare it only against an abstract ideal of a state rather than to the actual alternatives as they exist elsewhere in the world. At one level of analysis, this is the correct approach. What makes America exceptional is the set of liberal principles that it is founded on, and it’s by measuring the reality experienced by Americans today against these philosophical principles that we can identify our shortcomings and seek to improve as a nation. That’s how a number of important social reforms have proceeded: from a mismatch between the experience on the ground and the lofty ideals that characterize what this project should be all about.

But this is precisely why it is so important to separate our failures to live up to our own exceptional ideals from the failures of other countries to satisfy even the most basic standards of human rights. In America, we can tune into cable news or hop onto social media at any time of day to consume a constant stream of acerbic criticism of our country’s flaws. For most people in the world today, to speak publicly about their government’s human rights record comes with serious personal risk. Simply put, the United States can and should speak from a position of moral authority when it comes to human rights, because the mechanisms that enable their protection are built into the very foundations of the American political system.

Naturally, this reasoning is applicable to many illiberal and undemocratic countries throughout the world. But applying it to China today is of particular importance, because China is the only country that threatens to serve as a peer competitor to the U.S. as a world superpower. And, crucially, China is the only existing threat to the American-created international order based on the broad ideal of liberal democracy.

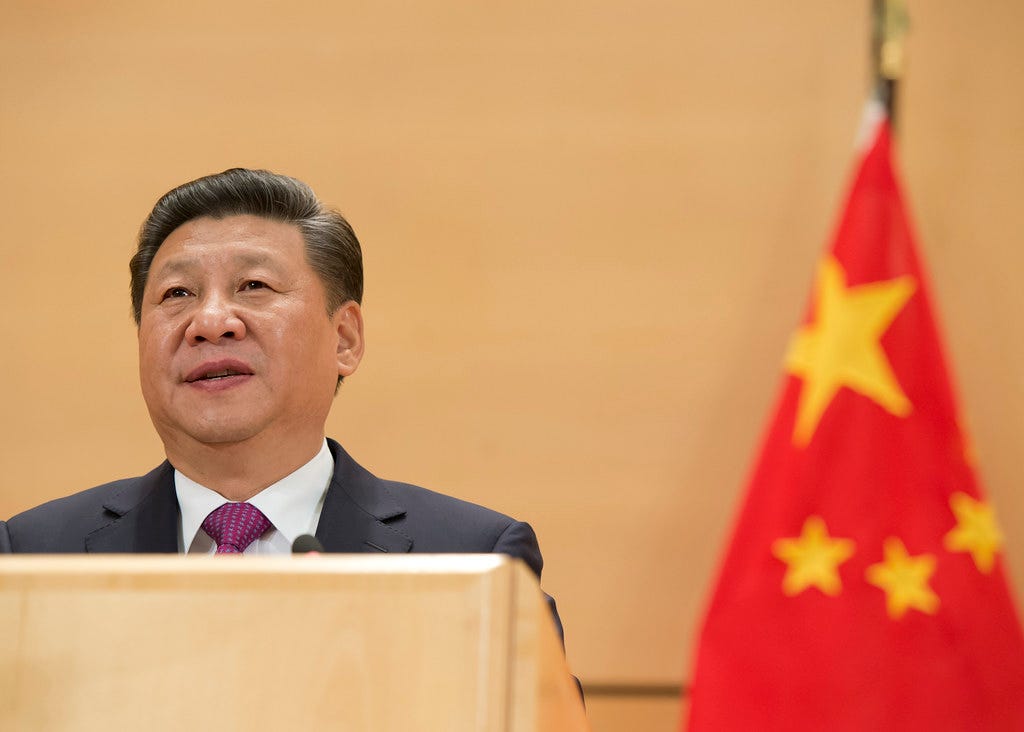

In no uncertain terms, China is seeking to reshape the world in its image. In place of the present system based on rules and norms that are (in principle) equally applicable to all nations, China is intent on creating a hierarchical system in which Chinese power alone dictates international relations. As Michael Schuman explains in his book Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World, a central piece in President Xi Jinping’s plan for China’s national rejuvenation is “reviving the traditional Chinese system of foreign relations,” a system in which all other nations were vassals to China, and specifically to China’s emperor, the “Son of Heaven,” who possessed the divine right to rule “all under Heaven.” Schuman explicitly connects this system to the present day:

The glory of Chinese civilization was to extend over “all under Heaven”—the entire civilized world. In the old days, limitations of technology and transport realistically limited the extent of China’s reach. Now, in the age of jumbo jets and instant messaging apps, the Chinese world order can literally go global. Xi has embraced this rejuvenated, expansive vision of China’s position within “all under Heaven.” The Chinese emperors never accepted other peoples as equals, and Xi sees no good reason to start doing so today.

The implications of China’s campaign for world domination are fairly straightforward when it comes to international trade and American military projection. But it also threatens the liberal conception of human rights that has been the basis for the international order for almost a century.

The most illustrative example of how China’s power has allowed it to challenge the very meaning of human rights is its “counter-terrorism” policies in Xinjiang. Beginning around 2017, the CCP imprisoned over one million of the region’s Uyghurs and other Turkic ethnic minorities in concentration camps on suspicion of “extremism,” “signs” of which include owning a Quran; having too many children; traveling abroad; having relatives abroad; not crying at funerals; quitting smoking or drinking; certain levels of household electricity usage; vehicle usage; exiting the home through the back door too often; and not socializing enough with neighbors. The CCP has also taken the children of the imprisoned population to be raised in state-run “boarding schools,” and it has systematically sterilized Uyghur women. At the same time, it has turned the entirety of Xinjiang into what has been aptly called an “open air prison,” where vast surveillance networks of AI-equipped facial recognition cameras and police patrols monitor Uyghurs wherever they go, even in their own homes.

The CCP has presented these genocidal policies as a superior alternative to the “ineffective” Western models of de-radicalization. Xinjiang has hosted international seminars where experts from around the world are apprised of the benefits of the “China model” of counter-terrorism. In July 2019, 50 countries signed a letter sent to the United Nations Human Rights Council that praised China for its “counter-terrorism and de-radicalization measures in Xinjiang,” characterizing them as “remarkable achievements in the field of human rights.” Meanwhile, China is actively campaigning for the UN to adopt its practically non-existent standards for facial recognition technology, and is exporting its dystopian surveillance technology directly to interested autocratic regimes throughout the world.

When we talk about protecting human rights in America, it is essential that we acknowledge this broader context. Our passionate disagreements about how to best live up to America’s founding ideals cannot be disconnected from the fact that China is working tirelessly to establish a new world order where the entire concept of human rights is inverted.

Not only does reiterating this context help us to push back against the encroaching evils of the CCP, it also serves to highlight the shared moral foundations of Americans across the political spectrum. Most of the debates on human rights in America are pretty removed from any actual context or comparison of what other powerful societies look like and how they operate. What if we more consistently compared America to her actually-existing competitors?

For example, would it be less compelling to claim that America’s criminal justice system is about “controlling certain populations” if we also made sure to talk about how, as of 2019, China’s criminal justice system (which is separate from its vast networks of extralegal re-education camps, forced labor camps, and “black jails”) has a reputed conviction rate of 99.965 percent? Would those who refer to American social media companies’ content moderation policies as “Orwellian” be more measured in their criticism if we also regularly consider that the Chinese government censors virtually all anti-CCP speech—even in the United States when it can? What if we kept in mind that the strength and survival of America is what keeps the world order from being taken over by a country that has imprisoned more political dissidents than any other in the world?

Would some of us be as quick to condemn America as a uniquely historically racist country if it were also consistently noted that China’s approach to racial justice is to teach children ethnic Han-supremacy in schools and to “re-educate” the “backwards” ethnic minorities in concentration camps until their entire identity is stamped out? Regardless of who happens to be closer to the truth on these issues as they pertain to America, we must recognize that, should the CCP succeed in its quest to control “all under Heaven,” our disagreements on human rights will be rendered at best irrelevant or, at worst, impossible.

After nearly two decades, the heuristic presented by the late Samuel P. Huntington in his book Who Are We? is more pertinent than ever: “Identity requires differentiation. Differentiation necessitates comparison.” The shared faith in the liberal conception of human rights that is foundational to American identity, in comparison to the expansionist, totalitarian, genocidal Chinese Communist Party, gets to the very heart of what differentiates our two countries.

Using the America versus China comparison more frequently in our discussions on human rights will help to remind us that the values we share with our political opponents—by virtue of us being Americans—remain more substantial than we think.