Jordan Peterson and the Social Superego

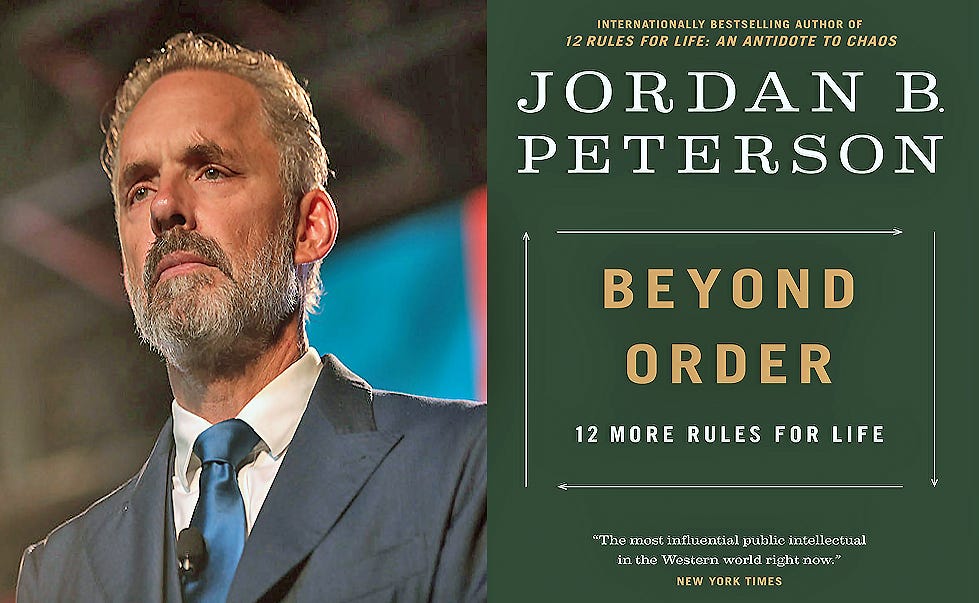

A review of "Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life" by Jordan Peterson

Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life

Jordan Peterson

Portfolio, 432 pages, 2021

Over 40 years ago, the historian Christopher Lasch reflected on the psychological consequences of social change in the post-war West. As government bureaucracies got ever larger and intervened in more areas of public and private life, they challenged traditional centers of authority, like church and family. Their interventions were often guided by the ideology of “welfare liberalism,” which favored a therapeutic response to social problems, neglecting (or even rejecting) traditional forms of self-reliance. Lasch echoed conservative critics when he argued that this “absolves individuals of moral responsibility and treats them as victims of social circumstance.” But he was most interested in the psychological changes wrought by these developments, which he believed had implications for the superego—the part of the personality which internalizes society’s moral standards and taboos.

Lasch believed that the new trends undermined “the social superego, formerly represented by fathers, teachers, and preachers.” Far from leading to a “decline in the superego” among individuals, he suggested that the bureaucratic revolution fostered the emergence of a “harsh, punitive superego”:

As authority figures in modern society lose their ‘credibility’, the superego in individuals increasingly derives from the child’s primitive fantasies about his parents—fantasies charged with sadistic rage—rather than from internalized ego ideals formed by later experience with loved and respected models of social conduct.

The phenomenal success of Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life can be partly explained by the enduring appeal of that old social superego, “formerly represented by fathers, teachers, and preachers.” During the sprawling speaking tours accompanying his last book, Peterson noticed that one idea resonated with his audiences more than any other: responsibility.

Peterson’s singular emphasis on the relationship between individual responsibility and the search for meaning struck a chord with audiences dissatisfied and disoriented by the moral terrain of contemporary life. His efforts to motivate the value of the Western cultural inheritance—not least Christianity—captured the imagination of a new generation of readers eager to know why the once-“loved and respected models of social conduct” might have had some value, after all.

12 Rules for Life was a blockbuster, making it a hard act to follow under any circumstances. But Peterson wrote Beyond Order under exceptionally difficult personal conditions which have been widely documented elsewhere and which the author explains in an introductory “Overture.” The book’s mere existence is therefore a remarkable achievement, and the enthusiastic commercial reception indicates that Peterson, and his message, remain much in demand among the reading public.

The central theme of 12 Rules for Life was captured in its subtitle, An Antidote to Chaos. Beyond Order instead “explores as its overarching theme how the dangers of too much security and control might profitably be avoided.” One of Peterson’s favorite motifs, the interplay between order and chaos is at the heart of some of the world’s most influential philosophical systems. Albeit in a less mystical sense, it’s also one of the central touchstones of the Western tradition, with the balance between freedom and order taking pride of place in the work of major conservative thinkers at least since the time of Edmund Burke. Notwithstanding his reservations about political conservatism (some of which are expressed in this book), Peterson is often bracketed in the media as a conservative figure. The book’s themes, as well as the author’s public profile, therefore suggest Beyond Order’s potential significance for the public reception of conservative ideas, even if this is ostensibly a self-help book.

Peterson has described himself as a “classical liberal,” so it’s unfortunate that Beyond Order takes few leads from key thinkers in British liberal philosophy, instead wearing the same central influences that Peterson has discussed elsewhere: Jung, Freud, Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky. Peterson’s vision gains power and clarity from its sense of focus, and as with 12 Rules, much of this book’s most interesting material comprises detailed interpretations of stories and myths from a variety of sources: The Bible, Egyptian mythology, the Harry Potter universe.

But this treads much of the same ground as his last outing, and it’s hard to escape the feeling that Beyond Order would have benefited from engaging with some new ideas. Moreover, while the trademark readings of religion and myth are frequently powerful, they sometimes come across as tendentious, à la Robert Graves or indeed most writers who read mythology according to their personal system. Is it really true, for example, that “the fundamental purpose of religious narratives is in fact to motivate imitation”? Might this not just be one among several functions, including binding people together in moral communities?

Peterson presents several anonymous case histories from his clinical experience, but the treatment of moral and psychological ideas commonly takes place at a very high level of abstraction. This makes the writing less engaging, with some passages verbose and portentous. In terms of style, Peterson might have taken a leaf from Jonathan Haidt, who has shown an enviable ability to draw in wide-ranging influences from science and philosophy while remaining grounded. Alternatively, Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, with its direct and practical explanations of moral psychology, is a classic example of how clarity of expression does not have to come at the expense of depth or sophistication.

Peterson does strike out for new intellectual territory in Rule 8 (“Try to make one room in your home as beautiful as possible”), which makes very welcome references to two English Romantics. Quoting at length from the poems of William Wordsworth and William Blake, Peterson seems less at ease with this material than with the religious narratives and myths explored in detail elsewhere. As such, the cursory discussion of these literary giants is thin and unsatisfying. Moreover, the Romantic who seems most relevant to Peterson’s thinking remains conspicuous by his absence. Among the English Romantics, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was the visionary thinker most concerned with the hidden meanings of myth and legend, and with the metaphysical significance of religious experience. He was the Romantic most deeply interested in science and psychology, even coining the term “psycho-analytical.” And after Burke, Coleridge was also among the first philosophers of political conservatism. One can almost feel Coleridge’s presence behind the text, waiting impatiently to be summoned onto the page.

Discussions of religion, philosophy, and psychology notwithstanding, Beyond Order is a self-help book, and the genre presents pressures in presentation. A central theme across Peterson’s worldview is that while suffering is a universal, permanent characteristic of our condition, we can adopt behaviors to mitigate that suffering and find meaning despite the tragic nature of life. The delicate tension between a tragically constrained vision of human suffering, and the motivational potential of meaning and self-transformation, is central to Peterson’s appeal. But these countervailing tendencies can easily be thrown out of balance, as quickly happens in Rule 1, “Do not carelessly denigrate social institutions or creative achievement.” Here, Peterson defends collective and individual achievement from unjust criticism. But the abstract discussion of social hierarchies shades into a Pollyannaish, merit-based apologia for the status quo.

Peterson distinguishes between the arbitrary exercise of power, and the authority that comes with “a competence that is spontaneously recognized and appreciated by others, and generally followed willingly, and with a certain relief.” Nobody rejects all authority, of course; whenever we get a haircut, call a plumber, or visit a doctor, we are implicitly acknowledging the authority of competence. Indeed, Peterson might have gone further, and made a point not explicitly stated: that authority has social value not because it primarily benefits the person in authority, but because it benefits either those who obey, or a third party. It’s the child who benefits most by obeying parental instructions not to run into a busy road; and it’s not the police, but innocent bystanders, who benefit from laws against drink driving. So, when authority is misused simply to benefit those who exercise it, we feel instinctive resentment.

Part of Peterson’s defense of authority is that “good people” are “possessed by the desire to solve genuine, serious problems,” and that this “variant of ambition needs to be encouraged in every possible manner.” Of course, everyone wants responsible positions to be filled by conscientious, competent people. But Western societies have governments of laws, not men. An overweening emphasis on the cultivation of individual wisdom underplays the importance of social processes and systems. The ideology of Imperial China, for example, placed enormous value on moral education; so much so that China became widely admired in Enlightenment Europe for its commitment to merit-based appointment to government office. But the structure of the political system meant the reality fell far short of the high ideal.

Because he bases his argument on the merits of those in authority, Peterson places himself on slippery terrain. Everyone knows that many positions, privileges, and sinecures are unearned, including in Western societies. Some rewards are merited; but others are the result of mere chance, the advantages of birth, nepotism, and myriad other factors. As Thomas Sowell explained in A Conflict of Visions, this is why major thinkers in the conservative tradition have not argued for Western liberalism on a meritocratic basis. Instead, they have located the moral justification for the Western system in “a social process, not of individuals or classes within that process.” Its justification lies in the combination of economic freedom, the rule of law, and constitutional protection of individual rights. Together, these make it theoretically possible for people to pursue what they find meaningful and desirable, taking their chance at life on the basis of legal equality, without their fate being determined in advance by some third party. If that is a modest goal, history suggests it might at least be an achievable one, unlike many more ambitious visions.

Writers in the motivational or self-help traditions are specifically concerned with inspiring people to improve their lot. This means they are naturally inclined towards merit-based justifications for the prevailing system of social rewards. In psychological terms, it is certainly more helpful to think that one’s sacrifices will be rewarded; and in free societies, they often are. But the West isn’t and has never been a meritocracy. Peterson’s presentation of the issues is potentially confusing about the historic achievements underlying Western liberty, and it therefore complicates his relationship with conservative thought.

A founding tenet of the Western tradition, embodied in the British and American political systems, is that when it comes to questions of power and authority, being “good” is not enough. Those who exercise authority must be constrained: not merely by their moral education, but by impersonal processes. If the right checks and balances are in place—whether in the public or private sectors—then there is only so much damage that a corrupt and cynical authority figure can do. A politician can be frustrated by another branch of government, and eventually voted out of office; a corrupt businessman can go out of business. Without such mechanisms, even the most well-intentioned individuals can wreak havoc. Of course, the existence of checks and balances doesn’t mean that individual virtue is irrelevant, either for personal or collective wellbeing. But this is more easily and objectively measured with respect to traditional standards of morality and civic virtue (like good manners, and not breaking the law) than subjective soul-searching.

Peterson in fact alights upon the central lodestar of conservative wisdom when noting that conservatives place more confidence in the “eternal verities of the Constitution and the more permanent elements of government … than on the too variable and too unpredictable whims of whoever might be elected.” And he in fact serves up an unintentional example of these “too variable and too unpredictable whims” in the form of a paean to the virtues of rule-breaking, albeit one couched in caveats and reservations. Peterson suggests that “if you understand the rules” and are willing to “fully shoulder the responsibility of making an exception”—because (you believe) it serves a higher good—“then you have served the spirit, rather than the mere law, and that is an elevated moral act.” This grants a license for violating rules and norms which might unsettle anyone alive to the self-deceiving nature of human morality. Who among us would not convince ourselves that our actions serve “a higher good”? Moreover, who can honestly say they will be the only person to “shoulder the responsibility”—that no innocent third party will share the costs of our rule-breaking? This might range from the pain and humiliation of family members to the erosion of constitutional procedures upon which the stability of an entire system might depend.

Peterson critiques perceived ideological weaknesses of both left and right. He notes that those inclined towards the right tend to be more attached to what has worked in the past, which helps them see the value in social institutions. But this tendency can also blind conservatives to the fact that “even once-functional hierarchies typically (inevitably?) fall prey to internal machinations in a way that produces their downfall.” Peterson thus sees “the liberal/left side of the political spectrum” as the one most likely to object to the “corruption of power.” But this is rather at odds with the fact that today’s lamentations about the “corruption” of august institutions—from the Church of England to the Ford Foundation and the BBC—are more likely to come from the conservative right than from the progressive left.

Among Beyond Order’s most political sections is Rule 6, which enjoins readers to “Abandon Ideology.” Here, Peterson takes aim at “the commonplace isms characterizing the modern world”—including conservatism, socialism, feminism, postmodernism, environmentalism, and so on. The author considers these “isms” to comprise “axioms and foundational beliefs that must be accepted, a priori, rather than proven, before the belief system can be adopted.” Peterson thus not only equates widely disparate belief systems, but also appears to view adherence to any such worldview as tantamount to being an “ideologue.” Instead, he argues in technocratic fashion for “careful, particularized analysis, followed by the generation of multiple potential solutions, followed by the careful assessment of those solutions.” This is all well and good, but the fact that reality is often complicated does not mean that all causes or effects of social problems must be equally complicated. Sometimes the truth is much simpler than complex obfuscations designed to evade it.

As one of Peterson’s erstwhile interviewers, Helen Lewis, has observed, Peterson’s rejection of ideology rather ironically places him in sympathy with the postmodernism he so decries. But it also seems somewhat self-flattering and disingenuous. Everyone—not least Peterson himself—maintains a more or less sophisticated vision of the way the world works, based on “axioms and foundational beliefs,” which, if articulated with sufficient rigor, could be ultimately expressed as a coherent system. Such visions can harden into rigid dogmas, and people can become the prisoners of ideology. But it is flatly wrong (and a bit strange) to suggest that intellectual doctrines are a problem in and of themselves. Surely the point is to get better at judging the differences between them, rather than pretend we can discard them entirely? And what about the religions that just happen to end in “ism”—Taoism, Judaism, Buddhism, Confucianism?

At other times, Peterson addresses social institutions in language that cedes too much ground to the nihilistic perspectives he is anxious to refute. In the course of an impassioned and deeply felt defense of marriage, for example, Peterson suggests that people entering this union might be contemplating a “lifelong struggle” centered on the question of which partner is subordinate: “each might reason, as people commonly do, that such an arrangement is a zero-sum game, with one winner and one loser.” Elsewhere, the marriage vow is described as a “threat” which implies, “We are not getting rid of each other, no matter what.” One does not have to be a starry-eyed ingénue to consider this an unfortunate misconception of how most people enter married life.

There are also questions of style. Most obvious is that Beyond Order’s 12 “rules” are simply less elegant and evocative than 12 Rules for Life. When Peterson says, “Work as hard as you possibly can on at least one thing and see what happens,” one might wonder: How could anyone work as hard as possible on more than one thing? And how did “see what happens” survive the editorial process? Indeed, the book generally might have benefited from more aggressive editing. Peterson’s account of his experiences as a Soviet art collector, for example, introduces the eyebrow-raising claim that “While seeking them out, I exposed myself to a larger number of paintings, I like to think, than anyone else in history.”

To conclude: “difficult second album” syndrome is real, and it applies to books and movies as well as music. Allowing for obvious differences in medium and subject matter, the experience of reading Beyond Order called to mind the film Magnum Force, sequel to Dirty Harry. Rather like 12 Rules for Life, Dirty Harry was a divisive cultural sensation whose roaring success spoke to the allure of the traditional superego. But Magnum Force took the tale of Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan in a new direction, as he faced down a clique of police vigilantes. Like Beyond Order, Magnum Force was thematically concerned with the negative effects of too much security; it was only made after overcoming serious difficulties in production; and its strong central idea suffered in the execution. The result was disappointing, but Harry Callahan still had three good movies in front of him. There’s every reason to think the same applies to Peterson.

This was too long to read all the way. So maybe my comment is adressed beyond where I read.

Life is suffering. This is the insight of the Buddha, in India, 2,500 years ago. Peterson has not ventured out beyond the Western tradition. If he did, and studied the Buddha, he would understand that there's another path apart from "adopting behaviors to MITIGATE that suffering."

First is recognizing the cause of suffering: desire - craving pleasure, material goods, and immortality, all of which are wants that can never be satisfied - and ignorance. Rather than explain, see https://www.pbs.org/edens/thailand/buddhism.htm#:~:text=The%20First%20Truth%20identifies%20the%20presence%20of%20suffering.&text=In%20Buddhism%2C%20desire%20and%20ignorance,them%20can%20only%20bring%20suffering.

Not mitigating, but rather transcending.