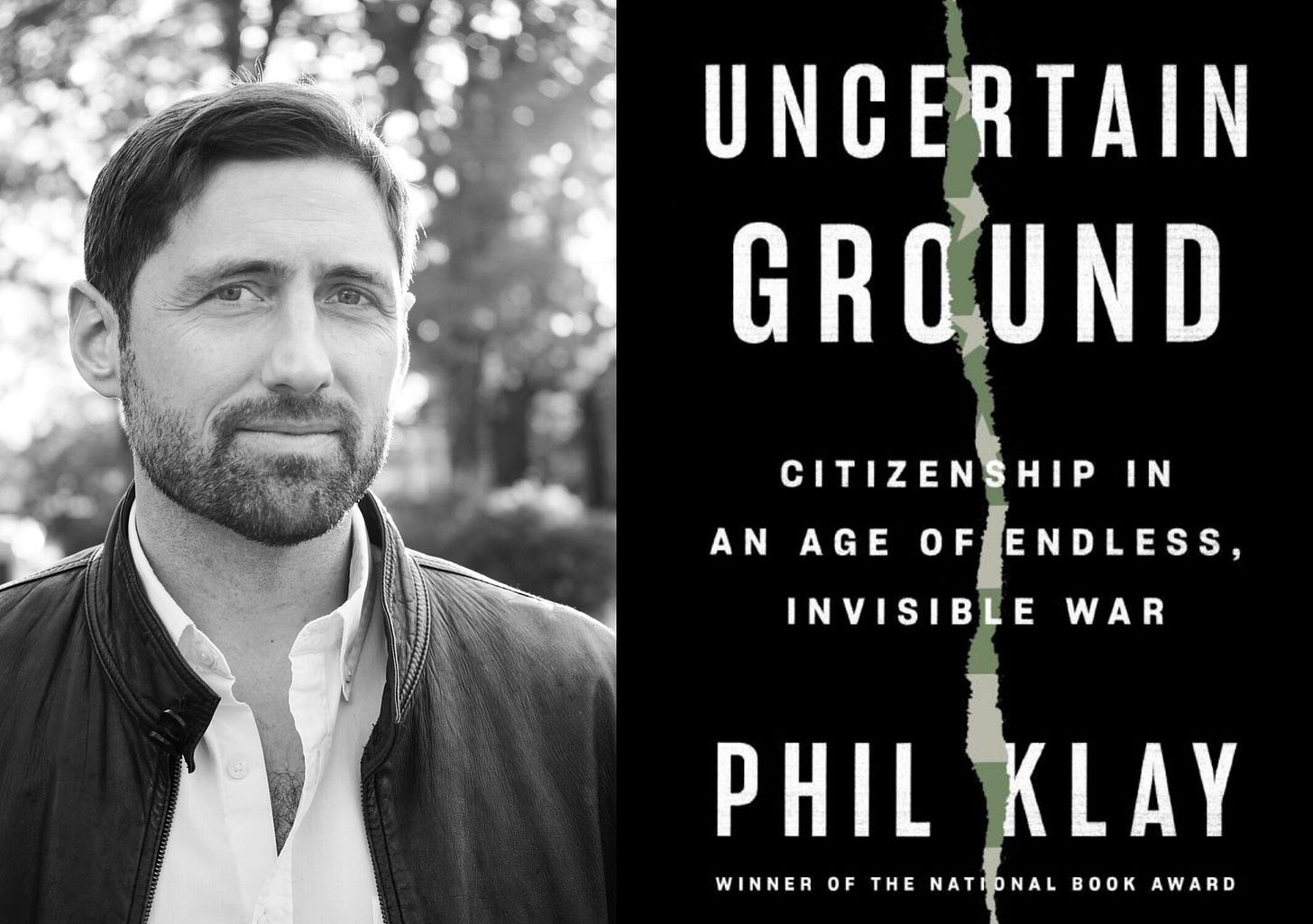

Uncertain Ground: Citizenship in an Age of Endless, Invisible War

Phil Klay

Penguin Press, 272 pages, 2022

“Talking about American wars,” Phil Klay writes, is “like talking about Schrodinger’s cat.”

Take this moment—right now, as you’re reading this review. Are we at war? Congress hasn’t declared war in 80 years; the Authorizations for Use of Military Force that sent troops into Afghanistan and Iraq were voted on two decades ago; besides, we’ve now withdrawn from both countries and our “military operations” there, those not-quite-wars, have ended.

But the Global War on Terror remains. Presidents still cite the 2001 AUMF to authorize deploying military force around the world. American drone strikes hit targets in Somalia, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Pakistan. From time to time, Americans wake up to news that servicemen have been killed in countries—Niger or Syria—in which they weren’t even aware we were fighting. American resources—money, weapons, intelligence—aid central American governments against guerrillas and drug cartels. We continue, in ways both strategized and ad hoc, to “project force,” as the euphemism goes. But force, like war, means violence.

Klay’s answer is simple: “Wherever we’re regularly killing, we’re at war.” So yes, he insists, we’re still at war. But only if you pay attention to it.

There’s an easy version of the book that could follow from this observation: a diatribe against American inattention, 200 pages on the folly of believing you can support the troops by going to the mall. That isn’t Uncertain Ground—Klay, after all, is neither a polemicist nor a pundit. A former information officer in the Marines, he’s best known for his fiction: Redeployment, a debut collection of stories about soldiers in or after Iraq and Afghanistan, won the National Book Award. His 2020 novel, Missionaries, turns to the intertangled wars on drugs and terror in Colombia and Afghanistan.

As an essayist, his interest is primarily on the consequences of American military force at home. There are limits to individual attention—he acknowledges this with a hopeful irony in “The Warrior at the Mall”—we can’t always pay attention to everything. But we need to reckon with the consequences of that inattention, he argues, singling out a Jonah Goldberg quip for criticism: “No one cares if Americans aren’t being killed, nor should they care if Americans aren’t being killed.” It’s the passive voice that reveals the flaw: American soldiers aren’t simply killed, but kill others on behalf of American citizens—and we should care whenever this happens.

Doing so is challenging, he acknowledges: “How to speak meaningfully of a conflict that has lasted so long, and at such a low ebb that most Americans can pretend it isn’t happening?” What effect does it have on us as citizens and as moral beings when we don’t pay attention to “the killing done in our name”? What does that inattention do to the men and women who kill for us?

The essays in Uncertain Ground don’t offer more than partial answers. Klay approaches them glancingly, incompletely, and in overlapping, sometimes contradictory ways. This uncertainty is not a flaw: these essays were written over the course of a decade; even within its four sections (Soldiers, Citizens, Writing, Faith), they’re organized non-chronologically. Losing one’s place in time reinforces the neverendingness of the War on Terror—almost all the essays feel like they could have been written as easily in 2010 as in 2020. The effect places us, as readers, on the title’s “uncertain ground.” This uncertainty is temporal, spatial—and moral.

It’s less important, he suggests, to find certain answers than to grant these questions our attention—to consider them and observe. The book’s final essay, on the fall of Kabul in August 2021, ends with a condemnation of the moral certainty that guided the early days of the War on Terror, “the warm glow of victimization” that united and gave purpose to the nation but which was “catastrophically destructive.” Even then, we were on uncertain ground. We just wouldn’t let ourselves see it.

So what do we see when we pay attention the killing done in our name? The answer varies based on the vantage from which we look. Klay’s four sections offer thematic groupings for his essays. But these are also roles through which he looks at war, paying attention as a soldier, as a citizen, as a writer, as a man of faith.

The first neither asks us to playact nor to defer to veterans—indeed, deferring to veterans on matters of war, Klay argues, is an abdication of a citizen’s moral duty, just another way of not paying attention. Rather, he draws our attention to the things, not always expected, that a soldier might attend to. In stories from Iraq and Afghanistan, these are sometimes uplifting, sometimes brutal, sometimes ironic. An essay on former Missouri governor Eric Greitens’s transformation from whistleblowing good soldier to disgraced fraud—and Greitens’s cameos elsewhere—highlight this uncertainty.

To look at the killing done in our name as citizens is to truly grapple with the moral risk involved in citizenship itself. Joining the Marines meant exposing himself to greater moral risk than he would otherwise have encountered—but this, ultimately, is what helps Klay to recognize that which all citizens share. The difference between innocence and responsibility is simply that between seeming and being: Unlike a civilian, it’s “impossible for a veteran to pretend he has clean hands.” But none of our hands stay spotless when others kill for us.

War’s changing shapes and innovations allow citizens to separate themselves from this reality. Observing that few Americans know a serviceman is a cliché by now. But even fewer know a Special Forces officer or a drone pilot, Klay notes—and these are the dominant ways we fight today’s wars. “You can’t embed a reporter with a drone or SEAL Team Six,” he comments drily: out of sight, out of mind. The result is a public “insulated from considering the consequences.”

This inattention spills across the political sphere, from a lack of congressional oversight, to erratic, incoherent presidential policies (a criticism implicating four administrations), to withdrawal plans that come across as attempts to avoid reckoning with war’s consequences for Iraqis and Afghanis. Perhaps, Klay made me wonder, this was what was most galling, even if unconsciously, about the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan: in its sloppy, ill-planned callousness, it expressed our desire as a nation to never think about Afghanistan or its people again—a wish we never quite murmured out loud, but one not so different from how we had spent much of the previous two decades already not thinking about the consequences of a war fought in our name, on our behalf, on this place and its people.

The moral risks of war matter because they do not limit themselves to war. This, at least, is the implication of “A History of Violence,” one of the collections longest essays—and one which makes no mention our 21st-century wars. It begins with the first recorded gun death in American history, the 1630 murder of John Newcomen by John Billington, who had arrived on the Mayflower. It would have taken Newcomen between 12 and 28 steps to reload his musket and fire again had his first shot gone awry. Compare this, Klay suggests, with the 2017 Las Vegas massacre, in which 58 were killed and 422 wounded in 10 minutes. The shooter fired over 1,100 rounds in that time—Billington would have needed six hours. “Billington might have had a tool suitable for murder,” Klay concludes, “but not mass murder.”

The story of that transformation is one of technological and strategic innovations born in military conflicts: simplifying and automating reloading, accepting that volume of fire might be more effective (and, in some circumstances, more lethal) than accuracy, more detailed knowledge of what bullets do on impact with the human body.

Moral risk spills outward from the use of military force: there is the moral risk of combat, and of asking others to engage in combat on your behalf, but also that of the technology of combat, the new or more refined tools that we build with each war. These trend toward distance and invisibility. In the Iliad, killing is as intimate as sex. In drone warfare as Klay’s fiction depicts it, it’s disconcertingly like a video game with poor graphics. In Las Vegas, the shooter need never have opened his eyes once he began firing: the gun itself was fully capable of creating a chaotic, deadly, “beaten zone” without human guidance.

This isn’t just about blowback to the home front or debates about gun violence. In Missionaries, Klay charts the consequences of overlapping conflicts, each sending ripples outward. The lines between Colombia’s internal conflicts, a joint Colombian-American war on drug cartels, and the Global War on Terror blur uncomfortably, until Central America begins to look like just another overlooked front: Afghan veterans provide training and strategic guidance; others appear as “military contractors”; technology developed for the War on Terror stalks their targets. Our military involvement in Colombia spans the War on Terror’s two decades. In November 2002, the United States began sending military advisors; this past May, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin reaffirmed our security and defense ties with this “major non-NATO ally.”

If a novel’s suggestions are still too speculative, consider Ukraine, to which my mind turned repeatedly while reading Uncertain Ground. I don’t mean this as a comment on whether supporting Ukraine, whether financial or with arms, technology, and military intelligence is just or right. But the technological innovations of the War on Terror have tended toward the invisibility of war, at least stateside. How certain are we that a proxy war really so different? It’s a question Klay poses in Missionaries—and so I wonder: when we arm and supply the Ukrainian military in a conflict cast as a defense of shared civilization as well as Ukrainian sovereignty, are we in fact asking Ukrainians to kill in our names as well as their own?

As a matter of politics and law, this question is not new. How to negotiate the fine line between supporting Ukraine and being viewed as a combatant nation has guided public debate and administration action. But the moral question still looms: have we decided, in the quickness of our righteousness, to ask others to kill on our behalf without quite realizing it? The answer matters. Even a just cause can reveal how little we’ve learned—or how comfortably blind we’ve grown to citizenship’s most uncomfortable demands.

“What I did not expect,” Klay writes about the birth of his first child, “was how much he’d deepen the sadness with which I view the world.” Still, Klay’s essays do not despair. This sorrow leads him to something very different, a stubborn hope that perseveres even in the absence of optimism. If you accept responsibility for the mortality and survival of others, Klay writes, thinking of the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, “it must necessarily change your life—and not simply because it provides you with onerous, unfulfillable obligations toward a suffering world, but because it connects you in a real way to that world and becomes the means by which you might find transcendent joy.” Klay continues:

To take our obligations to our fellow man seriously means knowing we will never be able to adequately respond. It means knowing, at all times, that we should be moving toward a revolutionary change of heart, for the strength to act more fully, directly, and powerfully in relation to the agony existing not just overseas, but in the divided communities where we live. It means knowing we will fail, and knowing the glory of creation is there for us anyway. It means accepting that being responsive to suffering and attuned to joy are not different things, but one and the same.

The moral stakes of war matter not because of any quest for purity—I doubt Klay believes there is such thing as moral purity, in practice—but because they are the stakes that give meaning to life.

This isn’t to say that war only, or primarily, or best gives meaning. Quite the opposite: it’s that the stakes of fighting to defend your nation, or even just your platoonmates, might differ in intensity from those of being a parent, or a sibling, or a husband, neighbor, citizen, but not in category. Every act of responsibility for another involves moral risk. Whenever we ignore it, we ignore not just culpability but possibility.