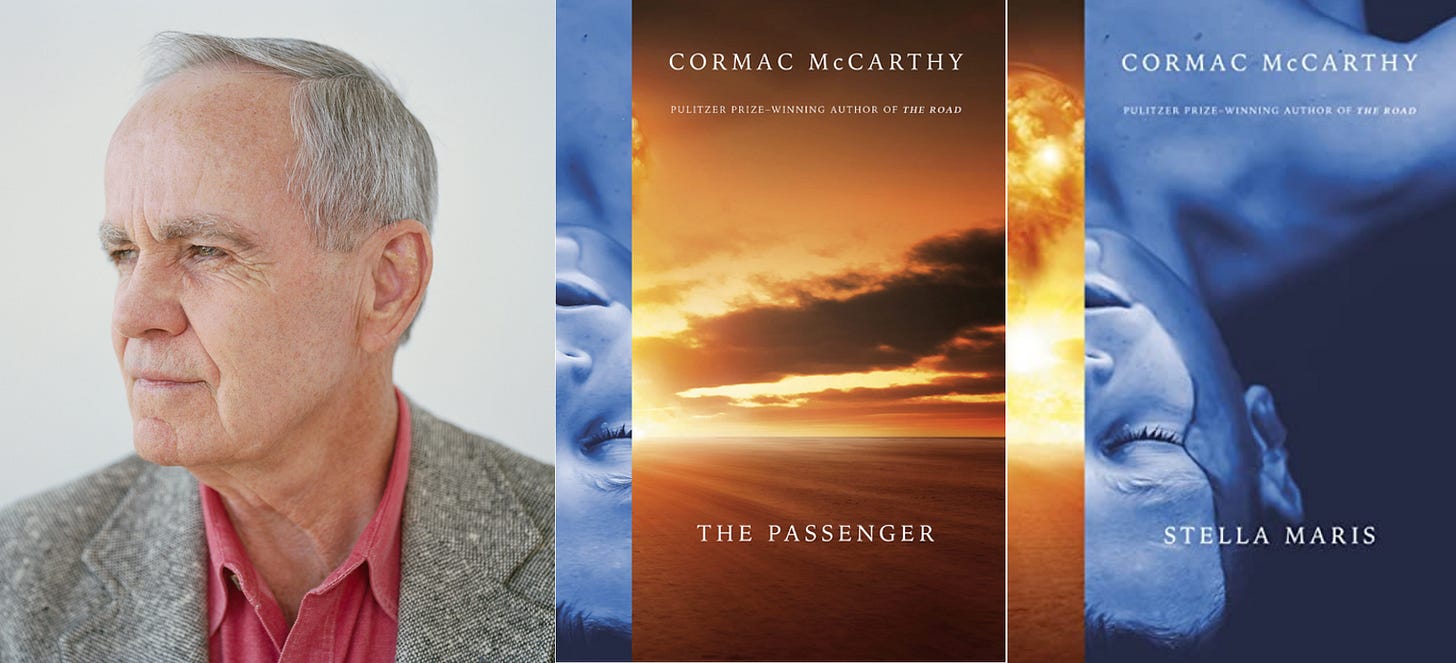

Nuclear Vaudeville

A review of "The Passenger" and "Stella Maris" by Cormac McCarthy

The Passenger

Cormac McCarthy

Knopf, 400 pages, 2022

Stella Maris

Cormac McCarthy

Knopf, 208 pages, 2022

The Passenger and Stella Maris, Cormac McCarthy’s first novels in 16 years, share a premise with David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: the first atomic detonation in the deserts of New Mexico loosed something unstoppable into the world—and, whatever else it has caused, or will cause, this event destroyed the life of a young woman decades later.

The experience of reading these novels is also a little like watching Lynch’s work: it’s hard to know what to make of them. Just what exactly are you reading: two novels or a single work? Are they really, as reviews and publicity materials have insisted, about religion, theoretical physics, and advanced mathematics? Is the occasional incoherence, buffered by moments of deep beauty and unexpected humor, deliberate or a story coming apart at its seams?

You can think of The Passenger and Stella Maris as thematic prequels to the apparent nuclear devastation McCarthy describes in The Road. The events that lead to that book’s waste lands are also those that lead to the births of the new works’ protagonists, Bobby and Alicia Western, whose parents meet during work on the Manhattan Project.

The Bomb haunts their family. The elder Westerns each die, young, of cancer. The children struggle to comprehend and to live with what they’ve inherited: mathematical talent—genius, in Alicia’s case—500,000 dollars each, in gold coins, that proves ruinous; a vague understanding of themselves as wandering Jews; feelings of unrelenting guilt in search of a cause.

Father, son, and daughter glimpse an evil they aren’t meant to and are consumed by it. It’s Alicia who sees most knowingly. Near the end of Stella Maris she describes a vision she had at age 12—what her psychiatrist might consider her first hallucination—the discovery of a hidden presence she calls the Archatron:

I saw through something like a judas hole into this world where there were sentinels standing at a gate and I knew that beyond the gate was something terrible and that it had power over me. … A being. A presence. And that the search for shelter and for a covenant among us was simply to elude this baleful thing of which we were in endless fear and yet of which we had no knowledge.

“The keepers at the gate,” she concludes, “saw me and they gestured among themselves and then all of that went away and I never saw it again.” This was not a dream, she insists:

I had no reason to believe that what I saw did not exist and that if that realm was unknown to us that didnt make it less threatening but more.

Alicia may have hallucinated her vision of the Archatron. Bobby seems to dream his, visitations from his father’s ghost. What their father saw, however, was quite real: he watched the Trinity test from the safety of a bunker, through goggles. Something in that moment became newly, immanently physical. The question with which McCarthy and his characters grapple, indirectly, is what that was: the expression and manifestation of mathematic equations? Or some old evil (or a new twisting of the soul), grown to new powers?

Readers meet Bobby Western, nearing 40, as a salvage diver in the Gulf coast states. When he’s not working, he lurks the barrooms of 1980 New Orleans, talking and worrying. As The Passenger opens, he and his team work to recover a 12-seat jet that’s crashed into the Gulf. The plane’s doors and windows are still sealed and the drowned bodies of nine passengers and two pilots float around them. But a passenger is missing, as is the plane’s black box. Bobby, too intelligent for his own good, keeps wondering about this after they resurface: someone must have been there already. Could the passengers have been dead before the plane hit the water? Could the plane have been planted there to make it look like a crash? The others are more content to take their money and not ask questions. But then—who had hired them, exactly? The client was unnamed, never seen, and paid cash.

He suspects some kind of dark conspiracy and begins to find it everywhere. No matter where he moves, his apartments are searched, first by two government agents in suits; then, he determines, by more nefarious (though unseen) figures. One member of the crew dies in a diving accident. His cat gets out and never returns. The suits keep coming by his bar haunts, looking for him. Bobby feels chased—and he seems chased—though it’s never clear by whom, or for what. The feds freeze his bank account and seize his Maserati. He thinks it’s for knowing about the plane crash; more plausibly, it’s what they say: tax evasion. Even the burglary of his grandmother’s home years before must be connected. Thieves took guns, but also family papers—his sister’s sparse written work and the notebooks his father kept as a Manhattan Project physicist.

The pursuit is Kafkaesque, McCarthy’s version of The Trial: neither Bobby nor readers ever know with certainty who pursues him, though he seems pursued; nor what crime he’s accused of, though he seems accused; nor what he’s guilty of, though he certainly believes himself guilty of something.

Alicia has been dead eight years by the time all this begins. Shortly before Christmas, 1972, she hanged herself in the woods outside the Wisconsin mental hospital to which she’d voluntarily committed herself, Stella Maris (also the second volume’s namesake). His younger sister’s death haunts Bobby; it’s among the things for which he holds himself responsible, though he was lying comatose in a German hospital at the time after wrecking a Formula 2 racecar.

Alicia was a mathematical prodigy; a high school graduate at 12, college at 16. Over the next four years, she began and abandoned doctoral work in mathematics—not because she couldn’t do it, but because she could do it too well. She sought to understand math’s nature—and couldn’t prove that any of it exists. She’s also been diagnosed as schizophrenic, though both Alicia and her counselor at Stella Maris, Dr. Cohen, doubt this: she, because she insists the figures she sees are real; he, because she doesn’t exactly meet the diagnostic criteria. Indeed, in Stella Maris, covering the last weeks of her life, she’s banished these visions—not with medication, but simply by telling them to depart.

These are the “Horts” (from “cohort”), a morally ambiguous group of bumbling vaudeville grotesques who begin to visit her not long after her vision of the Archatron. Their chief, the Thalidomide Kid, is a short, bald, papery-skinned figure with misshapen flippers for arms and a habit of comic malapropism in his verbose, cynical lectures—he’s the subject of Alicia’s conversations with her psychiatrist in Stella Maris and her discussions with The Kid pepper The Passenger, otherwise focused exclusively on Bobby. It’s not clear to her what the Horts or their motives are: they seem intent on distracting her, amusing her, perhaps protecting her. Later, she wonders if they were meant “to keep something at bay.” They seem to be hallucinations, but the novels posit other alternatives: supernatural beings; real, material creatures somehow unseen by most; aliens.

Alicia’s sessions with Cohen are built on intellectual gamesmanship. He’s trying to understand an atypical case for the sake of a research paper; she’s trying to push him to concede that he can’t, in fact, prove the truth of his (or any) reality over her own. In this world—the one you and I share outside the pages of the novel—I’d react as Cohen does. But The Passenger and Stella Maris exist in their own world, and here the Horts feel real. They are, Alicia insists, at least as real as mathematics.

Take geometry, she suggests. Like all math, it must start with an act of belief, postulating a reality that can’t be proven: “You begin with a point which has no dimension and therefore no reality and extend it into a line. Can an extension of nothing eventuate into something? You have to say so. You can’t show so.” Neither Euclid nor Riemann could reason their way out of this.

She’s discussing math and metaphysics, but McCarthy is discussing fiction itself. The act of imagination and belief on which Alicia insists geometry rests is as apt a description of both writing and reading fiction as I’ve encountered. E. M. Forster spoke of “flat” and “round” characters; walk into any writing workshop and you’re still likely to hear the task described in geometric language: depth, verticality, horizontals. To take an extension of nothing and eventuate it into something is the task of the novelist.

Something even stranger occurs in the minds of that novel’s readers. Seemingly without effort or even conscious thought, we manage to begin with points that have no dimension and extend them into lines, those lines into shapes. Alicia makes a similar point, but in narrative terms, when talking to The Kid:

I know that the characters in the story can be either real or imaginary and that after they are all dead it wont make any difference. If imaginary beings die an imaginary death they will be dead nonetheless.

This is true of Alicia herself from the beginning of The Passenger—on its first page, a hunter discovers her body in the snow. Another scene, in which she explains why she chose not to drown herself in Lake Tahoe, makes it viscerally true. At great length, she describes the effects of water pressure, near-freezing temperatures, and drowning reflexes in difficult-to-read detail. This is an imaginary character imagining an imaginary death. I was nauseated. In a way that not even Blood Meridian could, this depiction of death nearly made me vomit. My reaction was probably extreme. But my brain had taken this nothingness, these bits of ink on wood pulp, and transformed them into something momentarily real, forcing me to watch this young woman who has never existed die in slow motion, each of us fully aware of what nature was doing to her body.

Even if The Passenger and Stella Maris aren’t the final works the 89-year-old McCarthy offers us, they’ll still serve as a challenging coda to and commentary on what came before. That oeuvre is nothing if not a series of glimpses of the Archatron, from the near-supernatural figures of The Judge, Anton Chigurh, and all the demonic horrors of Outer Dark to the more mundane but deeply human violence his characters endure and inflict. McCarthy famously prefers the company of scientists to his fellow artists and, perhaps, his literary career has been its own, alternative kind of science, exploring the dark much as Alicia does: in notes, never finished, toward proofs and theorems, still unresolved.

On one level, then, you might say that The Passenger and Stella Maris offer a defense of the novel. Its inquiries are as equal and valid as those of mathematics and the sciences. Novels and math alike begin with axioms and posited ideas about reality that allow the rest to fall into place. You can no more prove the existence of a point, or a line, than you can the Archatron.

Or the soul. Bobby, on the lam and hiding in an abandoned shack, begins to have nightmares of childbirth—a stillborn, or perhaps extremely premature, or perhaps doomed, or perhaps monstrous infant. He asks of the doctor, “Does it have a brain?” “Rudimentary.” And then, a question to which no response is given: “Does it have a soul?”

Science can tell us a great deal about the human brain; mathematics can explore the workings of the physical space in which we exist. Neither can tell us much at all about the reality or the nature of the soul. That’s a task of no less importance, but perhaps one better suited to the tools of the novelist.

And yet: the same logic that suggests a novel might be a kind of alternative scientific inquiry also suggests it’s only as real, or truthful, as the Horts. Fiction, that is to say, might be just as misguided, distracting, and hallucinatory as the Horts—something we mistake as insightful when, in the end, it’s merely entertainment meant to redirect our attention from the truth of “an ill-contained horror beneath the surface of the world”—as Alicia puts it, that “at the core of reality lies a deep and eternal demonium.” Bobby’s view of this truth is disenchanted, materialist: that there might simply be nothing, just chance followed by nonexistence in which no one and no thing is remembered.

Unless, of course, it’s math that’s the vaudeville act. The question we’d rather not think about, but which McCarthy won’t ignore, is whether any of our quests for knowledge can be anything but mere entertainment and distractions in a world capable of annihilating itself. Or if they ever were, or could have been, anything different.