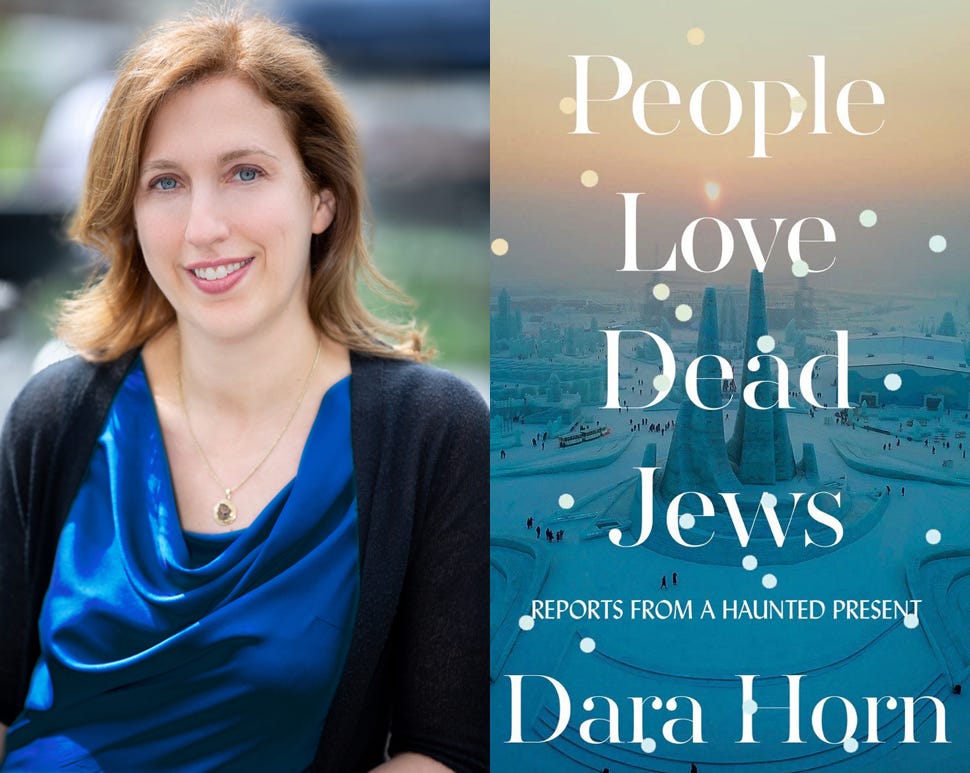

People Love Dead Jews—What About Living Ones?

A review of "People Love Dead Jews: Reports From a Haunted Present" by Dara Horn

People Love Dead Jews: Reports From a Haunted Present

Dara Horn

W. W. Norton, 272 pages, 2021

America has a Jewish problem.

It’s strange to write that sentence, but the numbers are plain. Ninety percent of American Jews say antisemitism is a problem in the United States. Eighty-two percent say it has increased in the last five years. And this isn’t simply a Trump-era phenomenon: those who say American Jews are less secure now than a year ago outnumber those who say conditions are better by three-to-one.

These numbers pre-date the January 15 hostage crisis in a Colleyville, Texas synagogue. They represent something that’s been in progress much longer: the resettling of scenery after the American Jewish community’s pre-pandemic annus horribilis. One crisis supplanted another, but the worry continued to simmer: that the post-war story of Jews in America was simply a happy chapter in a longer and more complicated relationship.

In October 2018, a gunman murdered 11 Jews at prayer in Pittsburgh; the following April, another shooter entered a synagogue outside San Diego. All the while, greater New York endured a spike in targeted street violence against Haredi Jews that culminated when, in December, attackers sought out Jews to murder at a kosher supermarket in New Jersey (but only because they couldn’t get into the Jewish elementary school next door, where dozens of children hid) and, two weeks later, at a Chanukah party in upstate New York.

Covid made that year’s sheer awfulness surprisingly easy to forget (or at least set aside), even for me, pressed into service to chair my synagogue’s hastily-formed security committee. I spent the second half of 2019 designing and explaining emergency procedures, meeting with security consultants, memorizing the locations of panic buttons and emergency medical kits, and learning how to pack gauze into a bullet wound (keep packing).

Dara Horn was pressed into a different kind of service. A talented and award-winning novelist, she became one of the country’s go-to experts to explain violence against Jews, past and present.

This led to an unsettling epiphany and the genesis of her new collection of essays: dead Jews were the kind of Jews publishers, editors, and readers wanted her to discuss. “People love dead Jews,” she explains in the first sentence of the first essay. “Living Jews, not so much.”

Horn’s essays on these murders form the collection’s three-part backbone. The first two appeared originally in The New York Times. The third didn’t. No one asked her to write about December’s dead. Instead, the coverage—on NBC or in The Washington Post, New York Times, and New Jersey Star Ledger—veered toward “contextualization” which, she writes, was “breathtaking in its cruelty.”

These dead Jews weren’t murdered by white supremacists or gunmen with ties to the far right, you see. And they weren’t like the other victims, either. Gentrifiers who shouldn’t have ever bothered to try to make homes or buy property where they lived, they’d caused “tensions” in the community. They wore black hats and black coats and shopped in their own supermarkets and didn’t get in their cars on Saturdays. They weren’t like you and me; they weren’t like their neighbors. They had it coming.

Yes, America has a Jewish problem, Horn confirms. And, in its distinctly American way, it’s because of precisely how and why Americans love Jews. Dead Jews are “people whose sole attribute was that they had been murdered, and whose murders served a clear purpose, which was to teach us something”—something “about the beauty of the world and the wonders of redemption.”

Another way of putting this is that post-Holocaust philosemitism failed not as a program but as a concept. It valued living Jews not in themselves but for the sake of the dead: for forgiveness, redemption, and progress. As an American and European self-help project, it was never about learning how to live with Jews, especially Jews who publicly mark themselves as visibly different from the culture around them. Instead, it’s about how learning from dead Jews could help the West be its best self.

Maybe this is why there are so many Jewish museums.

After all, the dead Jews of Horn’s essays mostly aren’t the dead of 2018-19 but those remembered and memorialized by Holocaust museums and Jewish heritage sites across the world. She’s not out to understand why some people kill Jews, but to investigate how the living, Jew and Gentile alike, remember and think about them.

She takes readers on a grand tour of these museums, from the Anne Frank House to the unexpected Jewish Heritage Sites of Harbin, an industrial city in northeastern China best known for its annual Ice Festival, to the immersive, “blockbuster” traveling exhibit “Auschwitz: Not Long Ago, Not Far Away.” It’s a theme so unifying, so apparent, that I’m surprised Horn doesn’t mention it directly.

But Jewish museums aren’t only physical spaces—not with digitalization and not after the widespread destruction of Jewish communities in World War Two (in Europe) and since the 1950s (in the Middle East). So her tour also takes us through the efforts of non-profit workers and scholars to recreate lost buildings and documentarians to capture living memory before it vanishes—virtual museums, if you will. In this context, her sharp-witted and sharp-eyed essay on listening to The Merchant of Venice with her 10-year-old son casts Shakespeare’s play as, itself, a kind of museum from Elizabethan England.

What do we do with all these museums? They share something in common: they’re all memorials to Jewish communities that no longer exist—even Merchant of Venice, written in an England that had already expelled its Jews but remained obsessed with them. Visit Jewish museums or heritage sites and, “instead of traveling the world and visiting Jews, you are visiting their graves.”

It’s for that reason I’ve always found Jewish museums, especially in the U.S. … not unsettling, exactly—just uncanny. I’m a flyover-country Jew, born-and-raised, so I should be happy to see cities like Omaha and Tucson build institutions that insist on their role in the American Jewish story. But these are museums housed, like their fellows in far off and largely Judenrein cities, in synagogues that have outlived their congregations. I note this, and shiver.

There’s a tension, maybe related, between the dead Jews of Horn’s museums and the living Jews around them: at the Anne Frank House, a staff member is asked to hide or remove his yarmulke while at work as it might “interfere” with the museum’s operations. Harbin’s heritage sites make no mention of the decades-long campaign of harassment that led every member of its 20,000-person community to leave between 1940 and 1962. And while everyone in Horn’s community was abuzz about the big Auschwitz exhibit, they told themselves that the swastikas appearing in nearby public middle schools weren’t really a big deal.

“Perhaps,” she worries, “we are giving people ideas.”

Of course, one is supposed to get ideas, or at least to learn something, from a museum. But what these are matters. Horn doesn’t discuss the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C.—an institution which to its credit largely avoids connecting dead Jews to some bigger yet somehow, always, easier moral lesson. What you’re supposed to learn is little more than the nausea you should feel on leaving.

Horn finds—and she is not wrong—a tendency in Holocaust museums and discussions of Jewish history to treat the horror as “a fancy metaphor for the limits of Western civilization.” Ph.D.-holding SS officers at Auschwitz listened to Mozart and read Goethe but did not love their fellow man enough. Well, obviously.

But the truest “moral” of the Holocaust might be something very different—not a moral at all but a fear that persistently ripples even through my affluent and enlightened college town. “The problem,” as Horn puts it, “is that for us, dead Jews aren’t a metaphor, but rather actual people that we do not want our children to become.”

There’s a way in which this fear becomes a temptation—just another way of focusing on Jewish death rather than Jewish life. That’s a difficult prospect for a parent and a potentially disastrous one for a community. Choose life, Moses charged the Israelites, that you might live. The prospect has always been more challenging than we like to admit.

So Horn ends with a surprising turn away from the news of more and more dead Jews, the growing attempts to explain away violence and harassment. “I was done with this sort of thing,” she notes, “which amounted to politely persuading people of one’s right to exist.”

Instead of joining New York City’s “No Fear, No Hate” march at the end of 2019, she drove her children to and from Hebrew School as usual. It’s one of the more mundane rituals of American Jewish culture but, she noticed, this choice wasn’t unlike the much larger gathering of New York’s Jews a few days later. Ninety-thousand people—four times as many as attended the march against antisemitism, nearly all of them from the visible and frequently-targeted Haredi community—gathered in MetLife Stadium not to mourn or protest, but to celebrate the end of a seven-year cycle of daily Talmud study.

As her book closes, Horn begins to use her phone not to doomscroll through videos of Jews being accosted or attacked on city streets in America and Europe, but to study Talmud herself. It’s a moving evocation not just of Jewish tradition, but of the power of tradition itself to be something like the opposite of a museum or a haunted house: not a place that preserves relics and replicas of the dead, but a space in which they somehow never die, where we can argue with them and they with us, and where these debates aren’t ethereal but build the substrate of life.

“Art is our chief means of breaking bread with the dead,” W. H. Auden once declared, but for Jews it has always been study that plays this role.

Yet the world keeps spinning. So 2019 may have been the annus horribilis, but it wasn’t isolated, or the end. The Texas hostage crisis was revealing: it followed a pattern familiar from the Jersey City and Monsey attacks of 2019. Once again, America’s leading institutions either didn’t know what to say or wanted to say nothing about antisemitic violence that couldn’t be linked to white nationalism.

The FBI, for instance, initially announced that the hostage-taker’s motivations were “not connected to the Jewish community.” They were. We now have audio of him before and during the attack making his hatred for Jews clear; he had been reported to British police a year ago for threatening to kill Jews. (They declined to investigate.)

Although the agency eventually walked back their claim, conceding that the hostage-taking was, in fact, “a terrorism-related matter, in which the Jewish community was targeted,” it had already fed headlines at the Associated Press, Boston Globe, BBC, and others effectively denying reality: Jews had been taken hostage, their lives threatened, for the simple fact that they were Jews gathered in a synagogue.

Just as worrisome are the ways the Covid-era brought the dynamics Horn describes to the surface of political discourse.

Jews as vectors of death and pestilence is an old lie, one used, as the bubonic plague ravaged medieval Europe, to justify the destruction of entire communities. American politicians were more tame—but they, too, began to openly blame Jews for Covid-19 spread by the end of summer 2020. They were also more selective, singling out Haredi Jews from the broader community, much as they have been (and still are) for antisemitic violence.

Bill de Blasio, for instance, merely targeted New York’s Orthodox Jews for admonition that “the time for warning has passed” and the threat of mass arrests, welded shut parks and playgrounds in Haredi neighborhoods while others remained open, and sent caravans of police cruisers through Crown Heights during Jewish holidays—not to protect the community that bore the brunt of the antisemitic violence he only reluctantly acknowledged as it spiked during his tenure as mayor, but to show the world how seriously he took Covid.

Andrew Cuomo was little different. Before his fall from grace, while pundits and politicians hailed him as the exemplar of Covid-era leadership, he too turned to Jews as his scapegoat. With one hand: a cover-up of the number of nursing home deaths caused by policies he refused to change. With the other: regulations openly designed to target Orthodox neighborhoods for the closure of schools, businesses, and synagogues on the eve of Jewish holidays. (And, on the screen beside him, a decade-old picture of a crowded funeral as evidence of Jews flouting Covid rules.) Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain; direct your fury at the man with the forelocks or the woman in a wig and ankle-length skirt.

What’s burbled up from the anti-vaccine right, on the other hand, can appear like an insulting but mostly innocuous embrace of Holocaust kitsch. But there is, in fact, something darker in the yellow stars pinned to their shirts, the periodic attempts to cast Anthony Fauci as some kind of modern-day Mengele, comparing vaccine mandates to Nazi-era race laws, or implying that Nazi “hygiene” laws invest public health as a field with genocidal intentions.

Indeed, the eye-rolling stupidity of Marjorie Taylor Greene’s ability to compare vaccine mandates to the Holocaust while also speculating that California wildfires have, somehow, been set by Rothschild-funded space lasers in order to (somehow) turn a profit reveals something obscured when the characters are less cartoonish: the temptation, both left and right, to shroud oneself or one’s cause in the redemptive and Christ-like innocence of dead Jews while finding the living, breathing ones at large in the world rather more suspect.

Its allure is old and widespread, Dara Horn shows. And, as our political discourse has grown increasingly exhausted, anti-social, and conspiratorial in the last two years, more and more willingly give themselves over to the simple—and false—answers it promises.