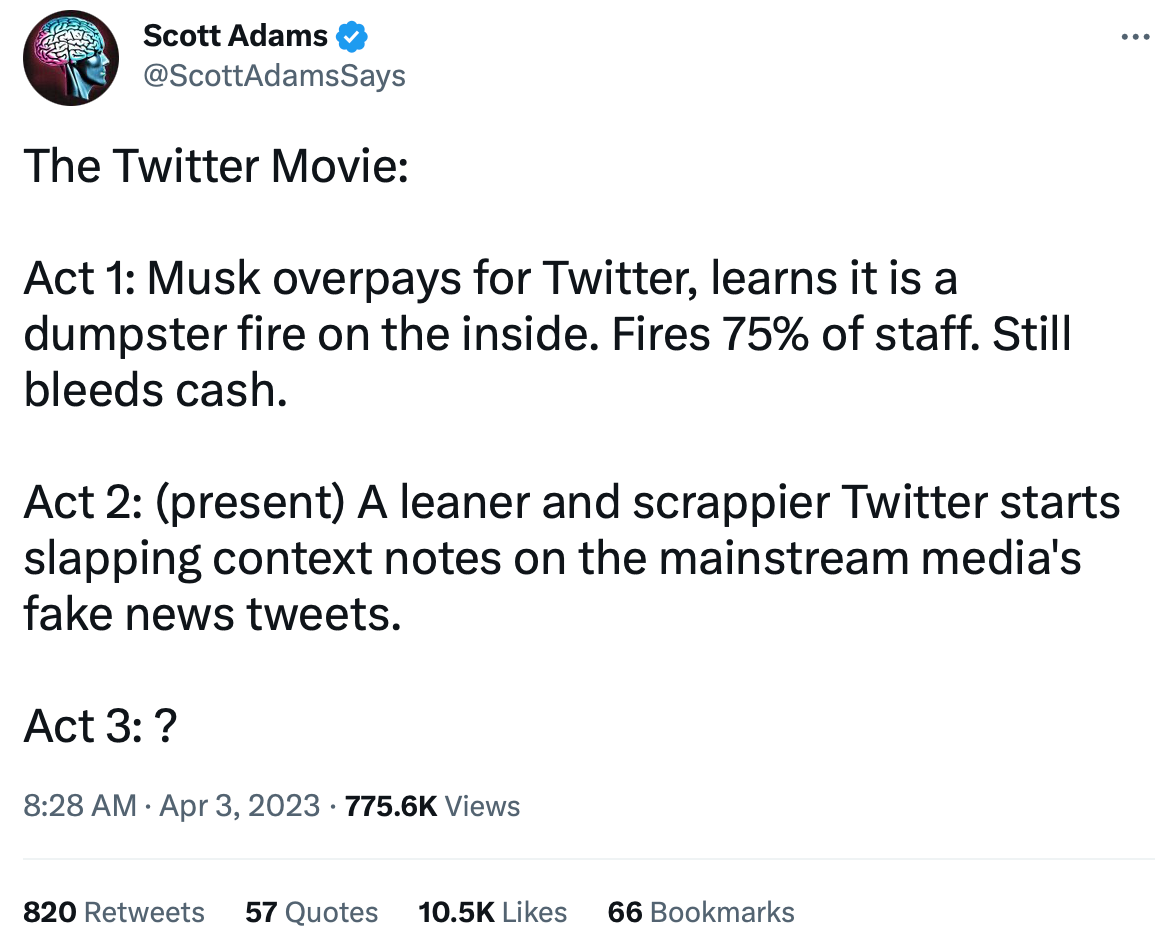

The Twitter Movie

Directed by Scott Adams

Scott Adams, creator of the Dilbert comic strip and cartoonish neo-segregationist, has unintentionally revealed how tribalism works.

All of us instinctively defend people we like. That’s completely normal and not worth agonizing over too much.

It’s human nature, after all, and although this trait can lead someone away from forming an accurate picture of reality, blessedly, there’s a fix: commit to regular self-examination about whether your biases—and we’ve all got them—are leading to perceptual errors of a drastic kind.

Adams, like nearly everyone in the IDW extended universe, likes and appreciates Elon Musk.

But liking and appreciating someone doesn’t intellectually justify selectively rewriting their story so that only the good bits get used. Nor does it justify tendentiously distorting their failures.

In a tweet yesterday about Musk and his acquisition of Twitter, Adams failed on both counts.

Adams calls this “The Twitter Movie,” but it’s less a movie and more a Dinesh D’Souza-style quackumentary.

Consider the absurdity of Adams’s framing.

Elon Musk, who routinely appears in lists chronicling the richest human beings in world history, is the poor, unfortunate, tragic hero who was lied to about Twitter’s problems!

That’s what Adams is suggesting when he writes that Musk “learns” that Twitter “is a dumpster fire” only after he purchased it.

Help me out here, is it normal for the entrepreneurially gifted to splurge tens of billions on companies without knowing the first thing about their internal operations? Seems less than ideal to me.

This is Musk getting a pass from Adams for making a disastrous purchase simply because he and Adams are ideologically aligned—which is textbook tribalism.

But instead of portraying Musk as a victim of pitiable misfortune, as if Twitter’s problems were undetectable from the outside, how about considering the possibility that Musk botching his due diligence this badly ought to puncture his reputation as an entrepreneurial genius?

If, however, you’re tribalistically committed to upholding his business savvy, as opposed to being clear-eyed about his performance in this space, it will look a lot like Adams’s tweet-length “Twitter movie” script.

And this is where our natural inclination to defend the people we like at all costs can do such a disservice to us, and to the people who listen to us.

Musk isn’t a business genius whose tenure as Twitter chief has only accidentally coincided with the site’s financially catastrophic losses. Musk is one of the world’s foremost business magnates, someone presumably competent enough to adequately research the ventures he takes on, someone presumably competent enough not to inflict billions of dollars in losses on a social media platform that he bought mere months prior.

Adams ought to get credit for acknowledging Musk overpaid for Twitter, but Adams then squanders it by treating a 44 billion-dollar purchase as if this was Storage Wars and poor Elon just couldn't have known what he was buying.

We should resist allowing personal affinities, or ideological alignment, to cloud our judgment—especially when it comes to the rich and powerful, who already get enough advantages as it is.