The Vermeulean Vision

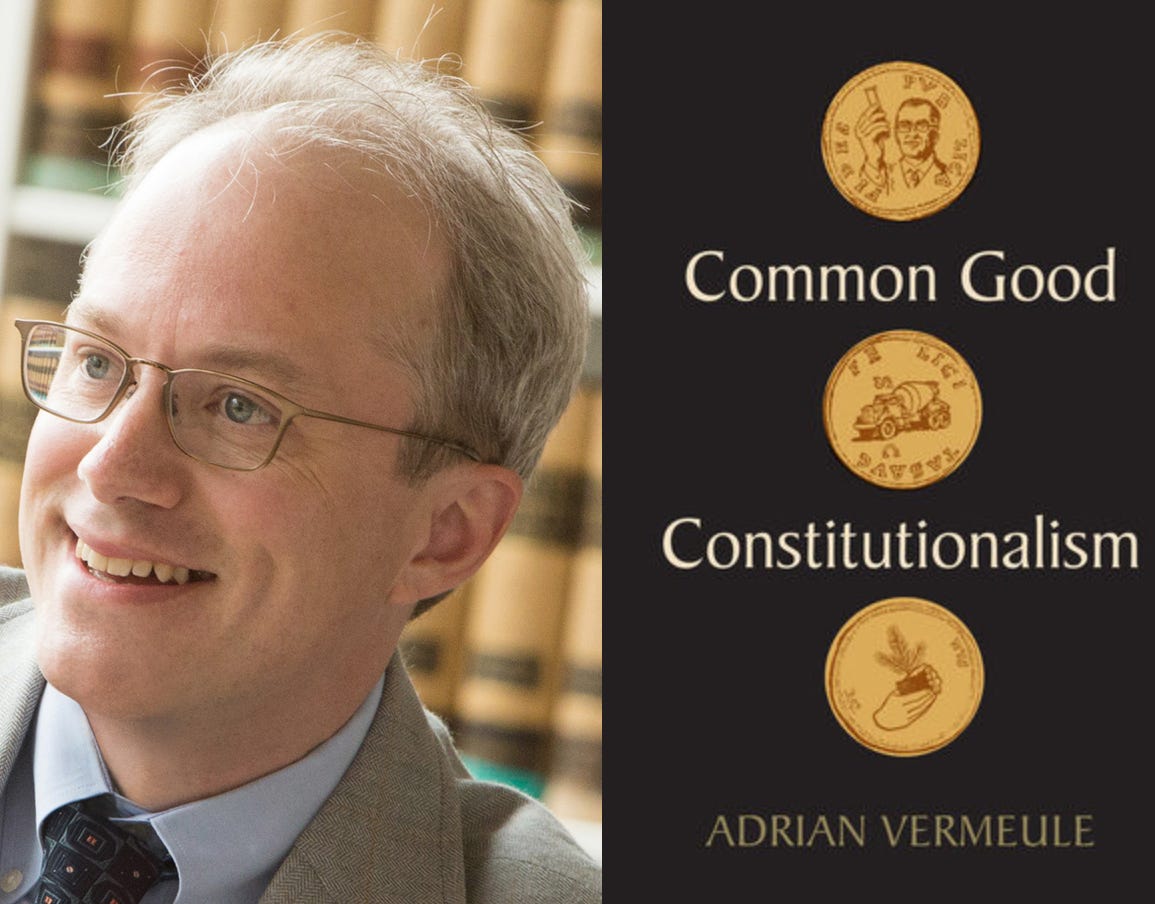

A review of "Common Good Constitutionalism" by Adrian Vermeule

Common Good Constitutionalism

Adrian Vermeule

Polity, 270 pages, 2022

“Some of the men of this age seem to raise themselves at moments to a hatred for Divinity, but … the neglect of, let alone scorn for, the great Being brings an irrevocable curse on the human works stained by it. Every conceivable institution either rests on a religious idea or is ephemeral. Institutions are strong and durable to the degree that they partake of the Divinity.” — Joseph de Maistre, Considerations on France

American political theory has recently seen the emergence of so-called “post-liberal” thinkers, whose clout is sufficiently large to warrant both critical and fawning appraisals in high profile outlets. Mostly coming from a right-wing Catholic background, the basic philosophical argument of the post-liberal thinkers is probably best summarized in Patrick Deneen’s 2018 book Why Liberalism Failed. In effect, it failed because it succeeded. Liberalism was committed to a nominalistic metaphysics which conceived of reality as little more than matter in motion. Lacking any belief in intrinsic goods or beauty, liberalism held that the only reasonable political system would be one where each individual was free to do as they wished within the lightly circumscribed limitations of liberal law. Initially this led liberals to support an allegedly “small” night watchman state. But as the cultural spread of liberal values overturned older religious and communitarian rivals, there was increasing pressure on the state to do more. Rather than referee the interactions of free individuals, the liberal state was to be proactive in eradicating the socio-cultural and even natural barriers to the exercise of amoral freedom. The result was the emergence of a nihilistic world where individuals were free to do anything, and apparently believed in next to nothing.

Despite the “post” prefix attached to their movement, it has never been clear that these authors are offering much more than a swift return to a more illiberal authoritarian social conservatism of the type a growing majority are happy to the see the back of; one of the reasons Sam Adler Bell cheekily pointed out “conservative elites, not unlike their progressive counterparts, are too weird to lead their revolution by democratic means.” This perhaps explains the ongoing attraction of post-liberals and so-called traditionalists to authoritarian states like Hungary (well analyzed by Paul Lendvai in his book Orbán: Hungary’s Strongman), Poland, and (until recently) even Russia. In each of these circumstances there is no doubt that a transition to such a state might be a novel experience; though rather like lung cancer, it might not be a pleasant one.

Given that they’re unlikely to implement that program through riding a wave of democratic popularity, some post-liberals have openly flirted with the idea of imposing their will juridically through a compliant justice system. This has provoked a scandal not just among liberals and the left, but even among conservatives committed to the ideal of a neutral and constitutionally bound system of law backed up by originalist interpretations of legal texts. Adrian Vermeule, a Harvard Law professor and polemicist associated with the (largely online) push for integralism, caused a minor scandal several years ago when he openly claimed that originalism was little more than a screen for advancing conservative causes, has served its purpose, and should now be abandoned for an openly right-wing approach to constitutional interpretation.

In his latest book, Common Good Constitutionalism, Vermeule offers a more robust defense of this position, taking aim at the sacred calves of right and left and arguing for full-bodied socially conservative interpretation of American law. In terms of the book’s quality as a legal argument, it makes some compelling criticisms. From a normative standpoint, whether you’re attracted to Vermeule’s common good constitutionalism will depend on whether you want to live in a proto-authoritarian regime where the demands of mass electoral democracy have “no special privilege,” because a democracy “may or may not be oriented towards the common good; one has to see whether it is, and the answer will depend on the circumstances.” And where rights are to be understood not so much as freedoms enjoyed by individuals or even groups, but always “ordered” [re: subordinated] or “tailored” to the common good because “that common good is itself the highest individual interest.”

If that is what it takes to save us from the vulgarity of liberalism, then I say bring on the Cardi B videos.

Positivism and Ronald Dworkin

What is intriguing about Vermuele’s position is how heavily and respectfully it leans on the arguments of Ronald Dworkin, the most influential Anglo-American legal theorist of the late 20th century and a profound defender of exactly the kind of egalitarian and permissive liberalism opposed by common good constitutionalism. While this might appear ill-advised or even paradoxical, Vermeule does an excellent job of articulating and reinforcing Dworkin’s seminal critiques of legal positivism generally and American originalism in particular.

When Dworkin was writing, the dominant tradition in Anglo-American legal theory was, and to a large extent remains, legal positivism. Its most important figure was the philosopher H. L. A. Hart, whose seminal book The Concept of Law was a vital foil for Dworkin’s early work. Hart described law as a “union of primary and secondary rules,” which simply means rules that directly govern social conduct and rules which confer powers. He also claimed that the concept of law could be analytically distinguished from morality, except for a “minimal content” of natural law required for any legal system to function. Consequently, when judges make decisions, they may very well be applying laws which many would consider unjust but which still count effectively as law. This is because their job wasn’t to be standard bearers for justice but to apply the law as impartially as possible. However, Hart conceded problems might emerge in what he termed “penumbral” cases. These are circumstances where the language of the law doesn’t seem to extend to new cases which it should nevertheless cover. In those circumstances Hart conceded that judges might have to be creative in their interpretation of the legal language to extend the rule to the new case.

In Taking Rights Seriously Dworkin exploits this and other tensions within Hart’s work to argue that in fact the positivist conception of law doesn’t give us a good sense of what judges are doing when ruling in hard cases. In Law’s Empire he criticizes Hart and other positivists for fixating myopically on legal language, what Dworkin called the “semantic sting.” Dworkin claimed that for many of the cases which most interested us as a society, the core controversies turned not on linguistic but moral issues. When considering how to interpret and apply the 14th Amendment—guaranteeing all American citizens “equal protection” under the law—Dworkin thought it absurd to argue that judges were just engaged in a “semantic” dispute over what the word equality really meant. This is in part because settling on the best definition of equality required one to move beyond linguistics and into the realm of political philosophy, seeing equality less as a word and more as a “principle.” We move from pedantic arguments about what the word equality means towards far more important questions about what is in fact the most compelling theory of equality under the law.

Most importantly, Dworkin actually thought it was possible to answer the question of what is the most compelling theory of principles like equality through philosophy; although an egalitarian left-liberal he had little patience for more skeptical flavors of radical thinking like critical legal theory. In his 1996 paper “Objectivity and Truth: You’d Better Believe It,” he condemned moral relativism and postmodern skepticism as incoherent, and by the time he published his career-capping Justice for Hedgehogs, Dworkin situated his arguments about the best moral interpretation of law in a vast theory arguing for an egalitarian liberal approach to morality, politics, and more. He also criticized conservative approaches to the law as largely unprincipled; particularly originalism, which offered both a deficient take on what judges in fact did and a profoundly unattractive—though often obfuscated—vision of what American law should be. In his analysis of Antonin Scalia’s defense of textualism, Dworkin claimed Scalia had “seriously misunderstood the implications of his general account for constitutional law, and that his lectures therefore have a schizophrenic character. He begins with a general theory that entails a style of constitutional adjudication which he ends by denouncing.” In other words Scalia was continuously compelled to draw on extra-textual resources to reach legal decisions, even if he often obscured that fact or perhaps was unwilling to admit that even to himself.

Vermeule’s Critique of Originalism

Throughout Common Good Constitutionalism Vermeule consistently states his agreement with Dworkin’s basic approach to law, even characterizing him as “the unsurpassed modern critic of positivism and originalism in Anglophone legal theory” whose “withering criticisms have never been successfully answered.” Of course he immediately adds that his use of Dworkin is purely going to be “negative” since Vermeule is repelled by Dworkin’s egalitarian liberal political philosophy. Nevertheless, Vermeule ruthlessly pushes Dworkin’s critique against his originalist rivals, subtly describing their convictions as an “illusion.”

Vermeule states at the outset that he resents how “allegiance to the constitutional theory known as originalism has become all but mandatory for American legal conservatives.” He also correctly diagnoses it as a species of legal positivism—sub par, I might add, next to the far more convincing versions articulated by figures like Hart, Joseph Raz, and, more recently, Scott Shapiro. After running through a description of originalist approaches to interpretation turning on the “context of discovery” and the “context of justification,” he launches “Dworkin’s critique” against them. Vermeule reiterates that Dworkin’s criticisms of Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia have “never been successfully answered.” Dworkin criticized Bork’s intentionalism and Scalia’s textualism by highlighting that both intention and “public meaning” are inherently ambiguous. Both legislators and the public often disagree on the meaning of many of the terms saturating the American constitution, such as “freedom,” “rights,” “equal protection,” “cruel and unusual punishment,” and others. So when judges claim to be interpreting the strict “original” meaning of these words, they’re either being disingenuous or lapsing into illusion. While history can obviously inform a judge’s opinion about what “cruel and unusual” punishment means, they wouldn’t be able to decide whether this should be construed narrowly or broadly without appealing to certain normative principles of political morality which are external to the originalist outlook.

Vermeule goes on to ridicule originalists like Jack Balkin who have tried to get away from these kind of problems by incorporating broader interpretive criteria into a self-described “living originalism,” claiming, for instance, that the text of the constitution shouldn’t be construed as consisting of words whose meaning is fixed once and for all but instead as a set of “general principles” which are sufficiently abstract to shift in application over time. He points out that by this point originalists have effectively ceded the entire point of their project. If the “original” intention of originalism becomes so watered down it becomes little more than a reverence for abstract principles, then what is the point in calling it originalism anymore?

As far as it goes I completely agree with Vermeule’s criticisms, and think he’s right to say they cannot be answered. As I’ve pointed out myself various times, originalism suffers from such a wide array of inconsistencies it is intellectually dead in the water; kept on cushy life support by massive injections of cash from the conservative legal establishment. I think that Hart is largely right that in plenty of cases it is possible to conceive of law as a set of rules whose meaning is semantically determined enough to apply them rigidly to the facts of a case; many reverse onus cases and Article II of the Constitution requiring the president to be over the age 35 are examples. But these are rarely the kind of cases originalists care about; you don’t see the Federalist Society pumping out op-eds about how we need to be more rigorous when making decisions about speeding tickets. The major constitutional questions in hard cases will always be settled in the manner Dworkin and Vermeule describe; though as I’ll explain, I derive very different conclusions from them on this point.

Vermeule’s Post-Liberal Critique of Liberalism and Liberal Law

Contrary to my expectations, for much of Common Good Constitutionalism I found myself cheering Vermeule on. This lasted until Vermeule launched his criticisms of liberal legalism, which have a fundamentally different flavor than the objections to originalism. The latter were close to a (rather bitter) family squabble over whose conservative theory of constitutional interpretation will prevail. So we have the odd phenomena of a deeply illiberal conservative commentator leaning heavily on a liberal icon to criticize his conservative peers, and who largely endorses Dworkin’s view that judges should be active in interpreting the law to bring it in line with the best political philosophy. But Vermeule’s disagreements with liberal legalism reflects a far deeper animosity than his rejection of originalism and positivism; Vermeule has made no secret of his disdain for the liberal tradition. Indeed, at points he even outdoes comparable critics like Deneen, who at least acknowledged there were redeemable and even necessary facets to liberalism; in his paper “Liturgy of Liberalism,” Vermeule venomously attacks “its inconsistencies and hypocrisies, its vehement commitments that seem out of step with liberalism’s own professed principles.”

Beneath all his devastating technical objections to originalism is his conviction that it has already conceded too much to the modernist liberal project. While originalists like to think of themselves as fundamentally different from waffly “living tree” constitutionalists, Vermeule thinks the distinction is more of emphasis than type. Originalists largely accept a certain liberal view of law as a neutral arbiter created by democratic sovereigns, to be applied by impartial and technocratic judges. This is also why they’ll sometimes pump out progressive decisions, as with Neil Gorsuch’s affirmation that sexual orientation is a prohibited ground of discrimination in Bostock v Clayton County. Gorsuch claimed to simply be applying the letter of the law in its most literal meaning; a claim Vermeule thinks is nonsensical since no judge can avoid bringing their normative principles into cases like this. Since Vermeule thinks homosexuality is immoral—challenging the “settled mores of millennia” and a violation of “natural law”—judges should have decided to allow homophobes to continue discriminating against LGBTQ individuals if they so wish. Which, for that matter, is what judges guided by “common good” constitutionalism would have decided. If this requires playing down the more liberal dimensions of American law, Vermeule admitted in a recent paper that Catholic integralists like himself “work within a liberal order towards the long-term goal, not of reaching a stable accommodation with liberalism, even in a baptized form, but rather with a view to eventually superseding it altogether.”

This is where we run into some real disappointments, and where the comparative problems with Vermeule’s reasoning become clear. The difference between him and someone like Dworkin is the latter spent a tremendous amount of time and effort meticulously defending his argument that egalitarian liberalism constituted the best possible political theory, and the one best fitted to the founding principles of American law. By contrast, Vermeule offers us next to nothing as a positive justification for his right-Catholic political philosophy, which is simply asserted in manifesto-like form at the beginning of the book and in a discussion of applications at the conclusion. There are a handful of references to the authority of classical natural law and the occasional Burkean flourish of appealing to the settled “wisdom” of millennia, but no attempt to argue for the cogency of either. This is remarkably thin stuff given we’re talking about viewpoints a majority of Americans and legal officials reject, not to mention the by now centuries worth of critiques launched against the teleological and theological underpinnings of classical natural law. It may be the case that God has revealed higher truths to Vermeule that are not explicable to mortal men, but I suppose the rest of us are supposed to take it on faith that living in an authoritarian Catholic state would be a blessed condition. Given the violent historical track record of these regimes, ranging from the repression of Estado Novo to the outright brutality of Francoism, I have my doubts.

In the absence of positive arguments what we get are negative criticisms directed against the ideological hegemony of liberalism. This gives the book an appropriately Nietzschean air of ressentiment against being unable to tolerate or to overcome the modernist present, especially in long passages in which Vermeule affects withering disdain towards the “sacramental” pieties of liberalism’s claims to be “overcoming … the unreason and darkness of the traditional past.”

One of Vermeule’s criticisms is the by now mechanically wheeled out objection that liberalism lacks a “substantive vision of the good,” being solely committed to liberating individuals from any kind of constraint—including those constituted and imposed by “legitimate authority [and] respect for the hierarchies needed for society to function.” This is a caricature of liberalism by now too cliché to even elicit anger. While Vermeule may claim to be “impatient” with critics who argue he isn’t responding to this or that technical detail of liberal political theory, what one actually suspects is he just doesn’t want to be bothered with responding to the actual arguments they put forward. But as I pointed out recently, every liberal thinker puts forward a vision of the good life. Rawls and Nussbaum link their liberal commitment to freedom to overtly “Aristotelian” conceptions of human flourishing; Kant foregrounds the importance of the good will’s duty to obey the moral law; Adam Smith and David Hume mix Stoic and communitarian principles to highlight our sociability; and so on. Indeed, there is a sense in which liberals take the question of the good life far more seriously than Vermeule does. For liberals, the question of the good life is so complex and important we should never rest easy that we’ve discovered the answer. One of the justifications for something like Millsian experimentalism is to gather as much data on what lives are worth living by allowing as many experiments as possible. Moreover, no liberal thinker has ever argued that we should be liberated from all constraints—only those considered illegitimate. Vermuele’s objection is simply to assert that many of these constraints would in fact be legitimate, but without putting forward any argument to that effect.

One might strengthen Vermeule’s argument by suggesting that liberals certainly do have a substantive view of the good life—but one that is ultimately incoherent and nihilistic. This was of course the claim made most effectively by Alasdair MacIntyre in his classic book After Virtue, where he argued that without a sufficient metaphysical grounding in something like teleology liberal modernity winds itself into emotivist relativism in its more banal moments and the Nietzschean will to power in others. However, as others have pointed out, MacIntyre himself is unable to fully extricate himself from modernity by offering a genuinely robust metaphysical alternative that returns to the scholastic grandeur that died with scientific materialism. Instead he settles for arguing a kind of Aristotelian traditionalism wherein the horizon of meaning is undeniably immanent within finite human life.

There is much to be said in favor of this position, and I think some left-commentators have made good use of it. Nevertheless, it is subject to considerable weaknesses. In his great book A Secular Age, the sympathetic left-Hegelian philosopher Charles Taylor takes issue with these kinds of MacIntyrean arguments. He rightly points out that the presumption of a “fall” into modernity itself left Christianity off the hook for its own role in engendering a transition to the “Age of Authenticity” circa the Reformation and even the Augustinian emphasis on interiority and purity of soul found in the Confessions. From this perspective the kind of genealogies of modernity offered by figures like MacIntyre are too totalizing and undialectical.

Moreover, MacIntyre and his followers like Vermeule dramatically underestimate how the expressive individualism of the liberal Age of Authenticity is meaningful on its own merits, and that attempts to check it through the restoration of authoritarian traditionalism risk bringing about the state of inauthenticity warned about by Soren Kierkegaard, among others. In his extraordinary Attack on Christendom, Kierkegaard pointed out how the demand for a social and conservative Christianity precludes and even pollutes the possibility of real spirituality by making the existence of God turn on the needs of humankind, rather than vice versa. By transforming spirituality into a means of achieving social solidarity, it warps the individual’s religious relationship to God by making faith into a functionalist glue authoritatively imposed by the merely ethical. It forgets that the way is always to be made harder, not easier; Vermeule and others want their religion on the cheap. In the end they would end up creating a world of idolatry.

The second main argument Vermeule makes, consciously echoing the fascist jurist Carl Schmitt, is that liberalism’s vaunted respect for personal and political freedom through the careful division of powers and legal neutrality is in fact a failed attempt to avoid the political—which, for Schmitt, meant the fundamentally existential decisions about which theological views we are to adopt. This is because liberalism is a substantial political theology which imposes itself across society and precludes competitors from gaining or exercising power. This can be seen in the multiple ways that liberal activists and jurists impose constraints on conservatives, often hypocritically in the name of liberating people from illegitimate constraints. Of course Vermeule doesn’t have a problem with the state imposing constraints for conservative purposes; the problem is that right now it is liberals who are in the driver’s seat. The point of this objection is to make the distance between liberalism and Vermuele’s integralism seem less stark, and to make his view appear more honest and less hypocritical since at least he acknowledges a willingness to use force to impose his preferred political theology. In contrast to wishy-washy liberals who talk a big game about tolerance but shut down conservative movements whenever they can.

This Schmittian objection does have real force, and liberal theorists have often been flummoxed in response to it. The “freedoms” guaranteed by liberalism should by no means be perceived as neutral, nor should the state be considered their impartial guarantor. To give just one example, one of the foundational difficulties with the right-liberal emphasis in asserting “natural” property rights against the state is that property is not a natural concept. It signifies a legal entitlement to exclusive use guaranteed by the coercive apparatus of the state, which enforces its own preferred scheme of property entitlements to the exclusion of others. This seriously inhibits the social freedom of members of a political community who may wish to distribute property entitlements in a manner different from the scheme backed by state violence.

The problem with Vermeule’s use of this argument is that political and personal freedom isn’t an either/or issue. There are gradations of political and personal freedom. Liberal theorists have strived to find the proper balance between constraint and freedom that allows people the most agency without destroying the social conditions which would make such freedom possible. This is where those detailed theoretical arguments Vermeule is so impatient with become important. Would that he had bothered to engage with Rawls’s large book about just how tolerant “political liberalism” should be and where constraint is acceptable. The scope of freedom provided by both liberal theorists and states is typically far wider than that of the kind of integralist authoritarian regimes supported by Vermeule, who doesn’t even believe that much in freedom anyways. To give a typical example, conservative commentators like Sohrab Ahmari (who praises Common Good Constitutionalism on its jacket) have complained that liberal law limits the freedom of right-wing groups by not allowing them the political right to impose their vision of the good life on society. And he is absolutely right. But the reason is that allowing conservatives the freedom to impose their vision of the good life on society through law would lead to far more serious constraints being imposed on LGBTQ individuals, religious minorities, and anyone else they think Thomas Aquinas would have a problem with. Vermeule and Ahmari may feel their agency is tremendously constrained by not being allowed to discriminate against gays to their hearts’ content, but most of us think the freedom of consenting adults to love whomever they wish is more important—not to mention more conducive to their living a good life of human flourishing of the sort Aristotle and others would appreciate.

Post-liberals have strained very hard to present themselves as edgy contrarians resisting the hegemony of the liberal state and its tyrannical bathroom policies. In fact, they’re not much more than the latest batch of reactionaries wheeling out the same hoary objections to liberalism that have been around since Joseph de Maistre screamed himself hoarse over the uppity peasants who just didn’t appreciate the sacred honor of dying so the house of Bourbon could occupy a new duchy in Germany. At some point it’s tempting to tell them “the Enlightenment happened. Get over it.”

Among the bunch, Vermeule has presented the most intellectually intriguing project so far—and he’s done so by turning the weapons of liberal jurisprudence against originalism and progressivism for the sake of social conservatism. There is much in his book that warrants admiration and even praise, particularly his critiques of originalism and pricking at the rhetorical excesses of liberal conceits. But the political philosophy underpinning common good constitutionalism is not just unattractive, but barely existent. It amounts to a brief program and a sequence of complaints, backed up by a deep misconstrual of liberal political theories Vermeule seems uninterested in rebutting seriously unless they can be reappropriated for his purposes. Just saying Ronald Dworkin has a “bad” theory of rights is remarkable in the face of thousands of rigorous pages defending just that theory. In the end, the problem with Common Good Constitutionalism is that it argues for a conception of the good that is neither common nor actually good.