Uvalde and Nashville: A Study in Contrasts

When police get it right vs when they get it horribly wrong

It is a testament to how collectively enraging we found the police response to the 2022 school shooting in Uvalde to be that, when the Nashville police department released body-cam footage last week of their officers neutralizing a school shooter with heroic decisiveness, all many of us could think about was Uvalde.

Uvalde

On May 24, 2022, 18-year-old Salvador Ramos entered Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, and massacred 21 human beings—19 of them children. He also wounded 17 others, but they survived.

If someone were to describe the Uvalde shooting with just these facts alone, they’d be guilty of underinforming you in an egregious way.

Because what makes Uvalde such a collectively haunting episode, over and above the tragic losses, is the role the police played in enabling Ramos’s carnage.

Almost a year later, I still feel a seething contempt for Uvalde police, who let down their community in unforgivable fashion. And I know I’m not the only one.

But what did Uvalde police do that was so bad?

The Texas Tribune summarizes a nearly 80-page report drafted by a Texas House investigative committee that painstakingly details the law enforcement failures that allowed Ramos to perpetrate the worst school shooting in state history.

In total, 376 law enforcement officers—a force larger than the garrison that defended the Alamo—descended upon the school in a chaotic, uncoordinated scene that lasted for more than an hour. The group was devoid of clear leadership, basic communications and sufficient urgency to take down the gunman.

Uvalde school police chief Pete Arredondo, one of the first officers to arrive at the scene, the law enforcement figure that other law enforcement figures on the scene assumed was in control, tried to squirm away from responsibility after the fact by suggesting he didn’t believe himself to be the incident officer, or officer in charge of responding to the unfolding school shooting. He said he assumed outside law enforcement would be in control.

There’s just one problem with that attempted defense: the active shooter response plan, drafted to establish a protocol for law enforcement to follow in situations of this sort, held that the police chief would “become the person in control of the efforts of all law enforcement and first responders that arrive at the scene.”

The person who co-authored that response plan? Pete Arredondo.

The action plan goes out of its way to say “all law enforcement”—meaning, Arredondo knew that even if there were law enforcement officers on the scene who outranked him, operational control remained his.

There is no way around it: this is an absolutely pathetic abdication of responsibility.

Yet Arredondo was by no means the only law enforcement figure whose inaction proved deadly to the very people police exists to protect. The Texas House report found that most of the officers who responded were federal and state law enforcement—nearly 250 of the 376 were either U.S. Border Patrol or state officers, not local police.

Here is how one New York Times write-up puts it:

The available footage shows high-ranking officers, experienced state troopers, police academy instructors—even federal SWAT specialists—came to the same conclusions and were detoured by the same delays the school police chief has been condemned for causing.

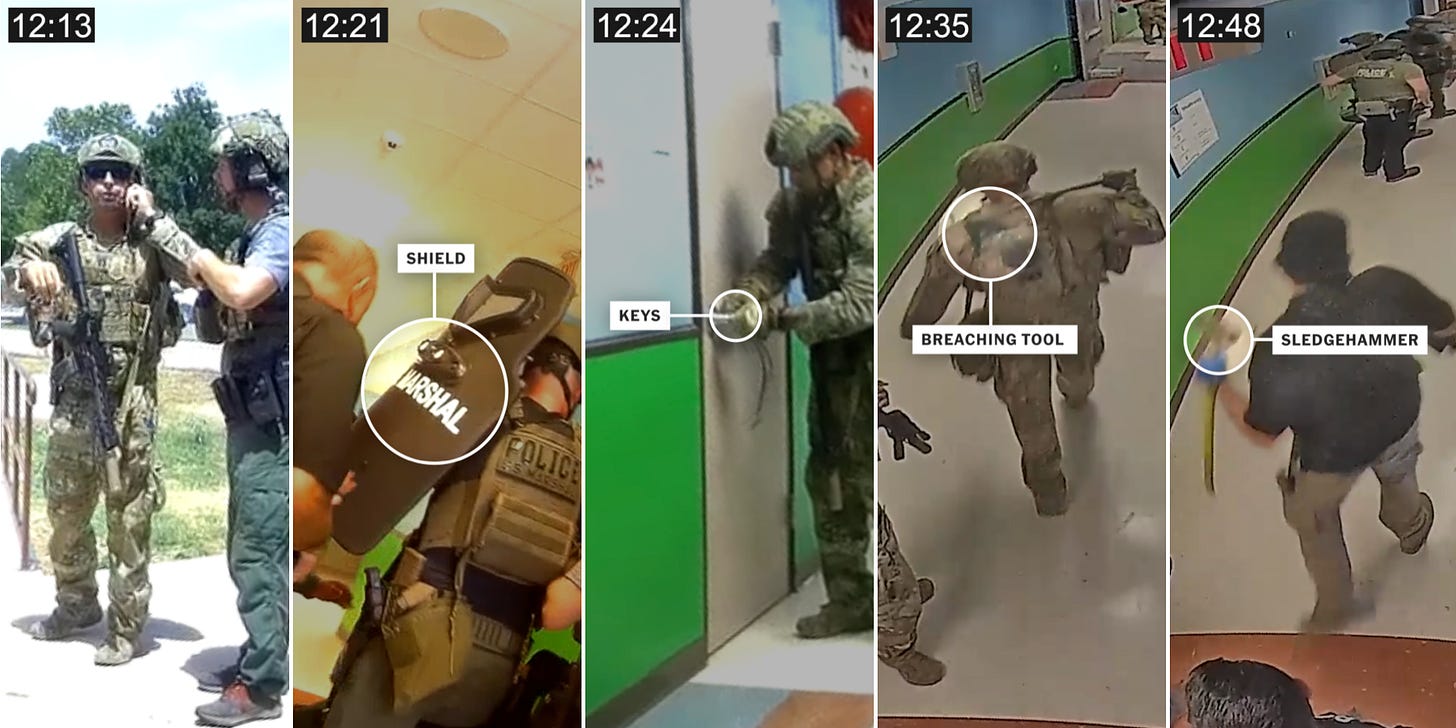

The officers waited for over an hour in the school’s hallways. Despite having full-body shields and superior firepower, they stood still. They didn’t breach, they didn’t advance, they just … waited.

According to an AP report, parents and onlookers at the scene pleaded with police to do their jobs. But those pleas fell on deaf ears:

“Go in there! Go in there!” nearby women shouted at the officers soon after the attack began, said Juan Carranza, 24, who saw the scene from outside his house, across the street from Robb Elementary School in the close-knit town of Uvalde. Carranza said the officers did not go in.

Javier Cazares, whose fourth grade daughter, Jacklyn Cazares, was killed in the attack, said he raced to the school when he heard about the shooting, arriving while police were still gathered outside the building.

Upset that police were not moving in, he raised the idea of charging into the school with several other bystanders.

“Let’s just rush in because the cops aren’t doing anything like they are supposed to,” he said.

The Texas House report concludes that there aren’t any “villains” in the Uvalde episode other than the shooter, but the conception it uses of villainy assumes malicious motives. In some cases, and I would argue this is one of them, cowardly inaction—especially coming from the very people entrusted by the community to keep them safe—absolutely qualifies as villainous.

Yes, you are the villain when your overwhelming law enforcement powers were put on the shelf at a time when children were being slaughtered a few feet away.

Too harsh? Listen to the audio recording of a terrified 10-year-old Khloie Torres pleading with police to come help.

Ramos is obviously the chief villain here, but tell me with a straight face that the police aren’t also villainous in their callous and cowardly inaction.

‘But hang on a sec,’ a skeptic might say. ‘Isn’t Uvalde a smaller community? Their officers aren’t necessarily capable of effectively responding to a situation like this.’

The New York Times’s Mike Baker documents the extensive training and tactical preparations Uvalde officers underwent to stop precisely these sorts of events.

Beyond these overarching failures, there were subplots of nearly unfathomable gutlessness.

Uvalde police officer Ruben Ruiz’s wife was a teacher at Robb Elementary, and was inside the classroom with the shooter, yet Ruiz’s fellow officers kept him from trying to save her. Reason journalist Robby Soave’s last sentence here is chilling: “She died while waiting.”

In addition to the failures of law enforcement at the scene, a Washington Post special report shows how air and ambulance delays made a bad situation worse.

In the final analysis, Uvalde law enforcement had everything they needed to quickly and decisively stop the shooter.

Instead, to their eternal shame, they prioritized their own safety.

Nashville

On March 27, 2023, not quite a year after Uvalde, 28-year-old Audrey Hale (also identified as Aiden Hale, a transgender man, by law enforcement sources) entered Covenant, a private Christian school, in Nashville, Tennessee, and killed six people—three of them children.

Although nothing about a school shooting that left multiple people dead is worth celebrating, it is worth noting just how markedly different the Nashville and Uvalde police responses were.

See for yourself.

An NBC write-up describes the police response captured by two officers’ body-cams:

As the officers enter the building with their guns raised, Engelbert and Collazo’s body camera footage shows split perspectives: Engelbert’s footage shows him and a group of officers searching for the shooter on the first floor before running upstairs, and Collazo’s footage shows his group initially running up to the second floor—where officers later encountered the shooter—and unsuccessfully trying to open a locked door before running back downstairs and following Engelbert’s group.

The twin-streams depict Nashville police officers relentlessly advancing, pushing forward with incredible bravery and competence, and putting down the shooter not long after initially entering the school.

The Nashville police department claims they first started getting calls around 10:13 a.m. (CT). In a data point that should recurringly infuriate Uvalde survivors and families of victims, not because of the decisive actions of Nashville police but because of what it shows the Uvalde police could have and should have done, the shooter at Covenant school was put down by 10:27. The mayor captured it well: “14 minutes, 14 minutes, I believe under fire, running to gunfire.”

Beyond their commendable response at the scene, Nashville police released information and footage that greatly aided the public’s understanding of what happened at Covenant school almost immediately after the events unfolded.

Perhaps the most damning footage of all is a simple video juxtaposition of the two police responses. (Of course, the “2 minutes in Uvalde” portion is a complete misnomer, since you would have to tack on over an hour more to give a fuller picture of Uvalde police inaction—but for tweeting symmetry, the 2-minute comparison is fine.)

The people of Uvalde, the defenseless children of Uvalde, deserved so much better.

The officers who let Ramos prolong his carnage undisturbed, who let Ramos turn Robb Elementary School into his personal killing fields, should wear that shame forever.