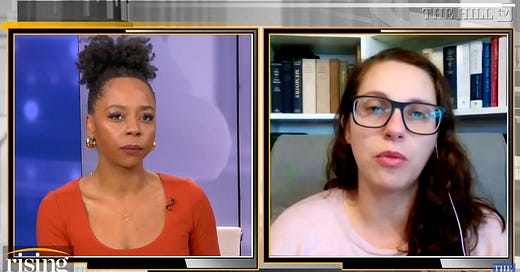

An antiwoke own-goal went viral when Bethany Mandel, who is making the rounds to promote her new book, Stolen Youth, co-authored with Karol Markowicz, was at a loss for words when asked by Briahna Joy Gray to define the word “woke” during a recent interview on Hill TV’s Rising program.

Here’s the tweet that shot the clip into infamy:

These things happen. People freeze up. Sometimes the story goes no deeper than that.

Other times, though, the freeze-up is revelatory—it can unwittingly convey something important about the discourse around a particular topic.

For example, one might plausibly take Mandel’s freeze-up to reveal an interesting aspect of woke discourse: the way “woke” can be a core idea in the right’s critique of the left, a fixture in right-wing rhetoric, a key adjective the right reaches for to signal that something is culturally toxic, while at the same time being a term so semantically slippery that a critic who is asked to provide a working definition of it goes into catatonic shock.

Still, why expect a momentary mental lapse on Mandel’s part to be an indicator that the term itself is flawed? Perhaps, as far as we can tell, the story here starts and ends with Mandel having a rough go, rather than her rough go being a sign that the term itself is deficient.

Two reasons. First, the word that gave her problems was “woke,” a term of nearly unrivaled culture-war salience. Had she stumbled over a word that is ideologically neutral or inconsequential, there wouldn’t be any sense in probing whether Mandel’s struggle to answer coherently reveals something deeper about right-wing discourse. If she froze up when asked to define the word “time,” as Augustine implied all of us would, I mean, what would that tell us? Not much. But she stumbled over a word that is currently ubiquitous in conservative commentary, a word that is supposed to capture an especially pernicious driver of lib misbehavior, which means that, potentially, her inability to straightforwardly define it tells us something about all those instances in which the specter of “wokeness” gets invoked by conservative commentators.

The second reason we should take this mess-up as revelatory is it just makes too much sense that Mandel would struggle when challenged this way—not, I should say, her in particular, but any of the right’s cultural critics who use “woke” as an all-purpose term. In other words, we should expect that when a political subculture has a category it uses in a nearly limitless way, to raise the alarm about innumerable related and unrelated cultural offenses, there will be occasions when, simultaneously, the term is (a) liberally used to criticize opponents yet (b) studiously kept undefined.

In fact, on these occasions, it would probably be right to say that (b) enables (a), that is, that its semantic nebulousness actively enhances its rhetorical omni-applicability. The discourse advantage to using a term this way is obvious: it provides maximal elasticity, granting conservatives a category they can extensively apply precisely on account of being so conceptually murky. So a freeze-up like this can reveal that the term’s power was at least partially coming from its invulnerability to being readily pinned down.

A related point that The Washington Post’s Philip Bump and others have made is that whatever definitions of “woke” people ultimately provide aren’t so much wrong as “immaterial” to the way the word functions in the conservative lexicon.

Perhaps it was just an insignificant freeze up, though. Then again, in an interview from not long ago, Mandel seemed to have similar issues articulating what she meant by “woke” or “wokeness.”

After the the clip went viral, Mandel offered a definition on Twitter:

One thing I want to flag from this definition is that it’s simply not the case that social-justice-minded persons would claim that “all disparity is the result of” institutional discrimination. They would say that many disparities are, but “all” turns this into an obviously outlandish thesis.

With the word “radical” appearing twice in short order, we’re obviously not dealing with a sympathetic definition here. That’s fine, of course. I only note that in case we judge this to be one of those times when we would actually prefer a definition that wouldn’t be summarily rejected by literally everyone hypothetically grouped under it. I’m not being sarcastic here; sometimes we’re okay with a hostile definition (e.g., “pedophile” is preferable to “minor-attracted person”) and sometimes we think a less contentious definition would be better.

But perhaps that’s impossible in this case, given that “woke” is now exclusively an antagonistic or hostile term. Very few who would today count as woke would use the word “woke” to describe themselves. That wasn’t always the case, but it is now. Which means a favorable definition might be out of reach. Still, maybe we don’t need favorable; maybe we just need fair.

The conservative commentator David French implicitly affirms the word’s contested status when he offers a buffet of definitions in a tweet, each representing a different perspective of the underlying concept.

Yet since “wokeness,” whatever it turns out to be, surely falls within the broader province of left-of-center social philosophy, let’s get a couple of definitions offered by leftists.

In “Unlearning the Language of ‘Wokeness’,” for New York Magazine, the leftist writer Sam Adler-Bell says that, unlike long ago when “woke” had a somewhat reliable meaning, its most common discourse function today is to signal that the person using it is either being unclear or intentionally deceptive in their critiques.

“Wokeness” may once have had a relatively stable meaning, signifying, among 20th-century Black radicals and artists, something like: “staying wise to the persistence and insidiousness of white supremacy in American life.” Now the term has been abused and stretched to a point of such ample unintelligibility that its mere appearance, in text or speech, reliably signals that an unclear or tendentious thought is about to be expressed — inducing, in me at least, a slack-jawed irritation that is phenomenologically not unlike having my ears boxed.

Nevertheless, Adler-Bell offers a definition:

Wokeness refers to the invocation of unintuitive and morally burdensome political norms and ideas in a manner which suggests they are self-evident.

Adler-Bell’s article was widely read, and its power partly came from the fact that the concept was being given affirmative attention by a leftist, as opposed to its typical treatment from that cohort: emphatic dismissal as nothing more than the dressed up grievances of conservative racists, as the progressive commentator Will Stancil argued in a lengthy thread. The leftist historical writer Dan Berger responded to Adler-Bell’s take more directly, but his critique was ultimately just as shallow as Stancil’s.

Another leftist, Freddie deBoer, who is a frequent critic of identity politics more broadly, offers a critical account of “wokeness” in a new piece.

“Woke” or “wokeness” refers to a school of social and cultural liberalism that has become the dominant discourse in left-of-center spaces in American intellectual life. It reflects trends and fashions that emerged over time from left activist and academic spaces and became mainstream, indeed hegemonic, among American progressives in the 2010s. “Wokeness” centers “the personal is political” at the heart of all politics and treats political action as inherently a matter of personal moral hygiene - woke isn’t something you do, it’s something you are. Correspondingly all of politics can be decomposed down to the right thoughts and right utterances of enlightened people. Persuasion and compromise are contrary to this vision of moral hygiene and thus are deprecated. Correct thoughts are enforced through a system of mutual surveillance, one which takes advantage of the affordances of internet technology to surveil and then punish. Since politics is not a matter of arriving at the least-bad alternative through an adversarial process but rather a matter of understanding and inhabiting an elevated moral station, there are no crises of conscience or necessary evils.

DeBoer goes on to list several attributes and discusses them at length. For example, attribute #2 is that “wokeness” is immaterial, which deBoer expounds on in this way:

[W]oke politics are overwhelmingly concerned with the linguistic, the symbolic, and the emotional to the detriment of the material, the economic, and the real. Woke politics are famously obsessive about language, developing literal language policies that are endlessly long and exacting. Utterances are mined for potential offense with pitiless focus, such that statements that were entirely anodyne a few years ago become unspeakable today. Being politically pure is seen as a matter of speaking correctly rather than of acting morally. The woke fixation on language and symbol makes sense when you realize that the developers of the ideology are almost entirely people whose profession involves the immaterial and the symbolic—professors, writers, reporters, artists, pundits. They retreat to the linguistic because they feel that words are their only source of power. Consider two recent events: the Academy Awards giving Oscars to many people of color and Michigan repealing its right-to-work law. The latter will have vastly greater positive consequences for actually-existing American people of color than the former, and yet the former has been vastly better publicized. This is a direct consequence of the incentive structure of woke politics.

My Arc partner-in-crime Nicholas Grossman had a brief but thoughtful thread that used deBoer’s piece as a jumping off point. Roughly, Grossman argues that when “woke” became right-wing shorthand for “leftist” or “progressive,” and when it began to be combatively applied to all manner of progressive actions and prerogatives, its original, more narrowly-circumscribed conception—the one more concerned with “speech codes” within “academic, journalistic, and online circles”—went away since it could no longer hold together the manifold ways the word was being used within the broader right-wing information ecosystem.

Patrick Chovanec, an economic and political commentator on the center/center-right, offers a more succinct take than Adler-Bell’s or deBoer’s.

Cathy Young, writing in our pages not too long ago, offered a full-length piece on defining “wokeness.” She sees it as a cluster of commitments:

Modern Western societies are built on pervasive “systems of oppression,” ones that are particularly race- and gender-based.

Everyone who belongs to a non-oppressed category in some core aspect of identity possesses “privilege,” enjoys unearned benefits at the expense of the oppressed, and is implicated in oppression.

Because various oppressions are so deeply embedded in everything around us, all actions that do not actively challenge it actively perpetuate it.

Challenging oppression and inequality requires not only combating injustices and reforming or dismantling oppressive institutions, but eradicating the unconscious biases we have all learned.

Language plays a key role in perpetuating oppression, and must be reformed and controlled to achieve equality.

Social justice advocacy must be intersectional—that is, must support all movement-approved forms of advocacy for oppressed identities.

Moral judgments of virtually any situation should be based primarily on where the people involved stand in the power/privilege hierarchy.

Young goes on to say much more, but these ideas capture what she sees as the concept’s main elements.

Damon Linker, another thinker with centrist sensibilities, defines it this way:

[T]he effort by progressives to take ideological control of institutions within civil society and use those positions to mandate that their moral outlook (and accompanying empirical claims about race, American history, and human sexuality and gender) be adopted throughout the broader culture.

Wesley Yang, a prolific critic of the various personalities and cultural trends that are standardly taken to be “woke,” talks at length about what he (somewhat grotesquely, aesthetically speaking) calls the “successor ideology,” which Yang has written a lot about but also pithily defines as “authoritarian Utopianism that masquerades as liberal humanism while usurping it from within.”

Since I don’t use the term so much anymore—mainly for the reasons Grossman points out in his mini-thread—I don’t see a need to offer a definition of my own. “Woke” and “wokeness” have been coopted by unthinking provocateurs whose slapdash invocations of it effectively transform it into an unhelpful pejorative rather than an illuminating descriptor.

I do think there are “woke” excesses that need calling out, and I don’t think those excesses are few in number or insignificant in their impact, but when I do call them out it’s usually via different language, such as “progressive identitarianism.” It’s not as economical, but what it lacks in succinctness it makes up in intelligibility.

“Woke” is simply an improvement of the Red Queen’s dictum: “Jam to-morrow, no jam yesterday—and never, ever jam to-day”

It's too bad we don't have consensus name and a canon for the ideology that "woke", "the successor ideology", etc. are trying to describe. Or, even better, if the people associated with these ideas identified with the name self-consciously. One of the virtues of Communism *as an ideology* is that it has an agreed-upon name and is founded on Marx's writings, which are extensive, coherent and brilliant, even where they have proven disastrous in practice.

The people who believe in this ideology really seem to see it as consisting in a series of moral imperatives, and by not naming it, or thinking of it as a proper ideology, they can simply presume its universality without having to examine the actual scope of these imperatives. If the ideology were a named phenomenon identified with some canonical texts, it would have to be defended intellectually in philosophical terms, rather than merely moral ones. This insistence on universality is probably the key to the naming and definition problem.

Last month, Thomas Chatterton Williams wrote an essay about "le wokisme" in French culture in The Atlantic. I think this French name has a nice ironic ring to it that addresses this resistance to naming. My preference would be to retain "le wokisme" as a standard.