Will America Take Its Own Life?

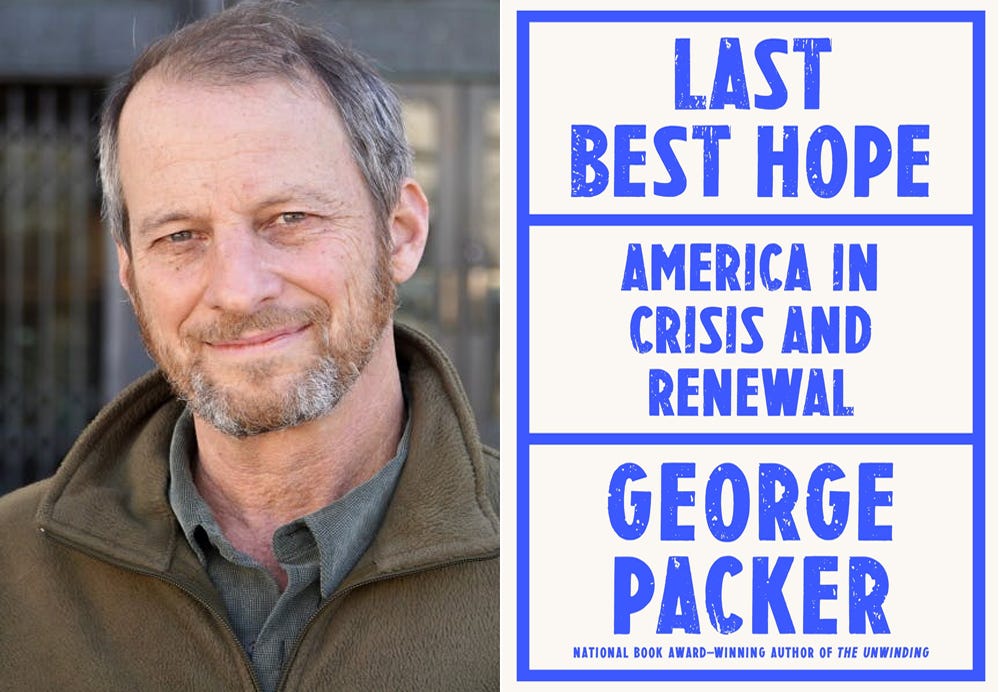

A review of "Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal" by George Packer

Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal

George Packer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 240 pages, 2021

Orwell said that the best books are those that tell us what we already know. Those kinds of books, whether well-written or not, tend to be pretty boring. George Packer’s latest work, Last Best Hope, fits this characterization—it told me little that I didn’t already know. And yet, with apologies to Orwell, it is not one of the best.

Packer has edited two volumes of Orwell’s essays and has self-consciously modeled his own prose style on Orwell’s. This has its advantages—much like Orwell’s prose, Packer’s has a pleasing directness, though like Orwell, it is not particularly rewarding in terms of humor or flair. Still, the subject matter of Last Best Hope is interesting enough to sustain one throughout. It addresses the pressing question: Will America commit suicide?

The notion of “civilizational suicide” has captured the imagination of many, from respectable historians to third-rate pundits. Arnold J. Toynbee and Oswald Spengler theorized about it; in 2014 arch-reactionary Éric Zemmour wrote a book on how France had committed suicide; and only three years later Douglas Murray predicted the death not only of France but of Europe as a whole. It is also with civilizational suicide that Packer opens his book. He begins by comparing America in 2020 with France in 1940 and quotes a speech by Abraham Lincoln: “As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.” If America perishes, Packer thinks, it will be by self-murder. Last Best Hope sets out his program for how to avert it.

Packer looks at America and finds it riven by competing factions in vicious culture wars—he sees how civic-spiritedness has evaporated, how formerly well-functioning institutions have crumbled, how the elites have discredited themselves while rising inequality has vitiated the middle classes. Americans no longer think of the common good or strive towards a common purpose; the county has been beset by political polarization. The very idea of America is at risk of dying. None of this is new to those who follow U.S. politics, but Packer (for the most part) puts it well.

Instead of a shared national narrative America now has four separate narratives—Packer calls them Just America, Smart America, Real America, and Free America. Free America represents libertarianism and the “Don’t tread on me” attitude. Its intellectual heroes are Hayek and Friedman, and since Reagan it has been strong among Republicans. Those who inhabit Just America care fiercely about social justice. This narrative has gripped the Democratic Party in recent years. Smart America is the meritocrat’s America. It flourishes among highly educated professionals—people with outsize cultural influence. And finally, the narrative of Real America is characterized by anti-intellectualism and the belief that “the heart of democracy beats hardest among the common people who work with their hands.” Sarah Palin is its outstanding representative. Packer—being the moderate bien pensant—tells us that there is some truth to each narrative.