The Third Algorithm

ChatGPT and other generative AI isn't about to create superintelligence, but even if what we see now is it, the impact is on the scale of Google search and algorithmic social media, except maybe worse

ChatGPT and other LLM software currently called “AI” will not turn into artificial general intelligence (AGI) or some sort of “superintelligence,” like the sentient computers of science fiction. The text and image generators we see now? That’s it, that’s the tech. The algorithms will get better, faster, more accurately responsive; people will develop new applications, incorporate it into new things, find all sorts of uses. But further development will be iterative, not revolutionary.

I’ve thought that for a while, because intelligence is more than computing capacity plus training data. The opposite has been the prevailing wisdom in Silicon Valley, with the biggest tech companies spending hundreds of billions of dollars on ever-larger data centers, so much it added half a point to US GDP. Belief in the coming of AGI approaches messianic, driven higher by investment-seeking hypesters, heavy drug users, and millenarian true believers, all of whom can reference science fiction, but not necessarily get it.

Maybe they’re right and I’m wrong, we’ll see. I’m not claiming humanity will never create AGI, or never reach the hypothesized Singularity, when advanced AGI can create even more advanced AGI, taking technology beyond human comprehension. Who knows. But I bet that, if we actually reach it, it’ll take another leap on par with LLMs, perhaps multiple leaps, and will not happen in the next three years. If that seems like a safe prediction to you, note that more influential people than I — tech CEOs, New York Times writers, senior government officials — claim AGI is imminent.

But in August 2025, AGI hype began to falter. OpenAI released ChatGPT-5, which CEO Sam Altman claimed “really feels like talking to an expert in any topic, like a PhD-level expert.” (It really doesn’t.) Not to be outdone in the bullshit department, xAI owner Elon Musk said that Grok, the company’s LLM, is “better than PhD level in everything.” (It isn’t close.)

Users were underwhelmed by GPT-5, because it’s a more advanced version of GPT-4, not a replacement for experts, let alone a step from superintelligence. Shortly after, Meta, one of the biggest spenders on AI, announced a hiring freeze.

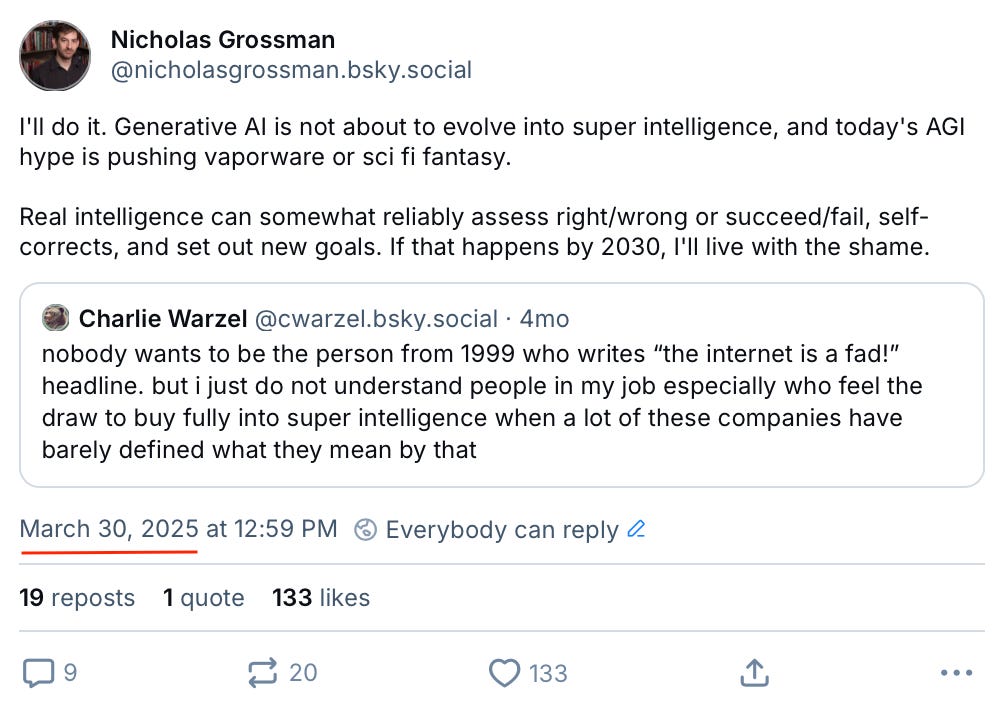

Maybe the bubble is bursting, or maybe it’ll turn out to be a bump in the road to sentient machines. For the record, I unreservedly announced my doubt months ago, at the height of the hype, when Atlantic journalist Charlie Warzel compared expressing AI skepticism in tech circles to someone in 1999 declaring “the internet is a fad.”

But while I admittedly want my prediction on record, the main reason I bring this up is that, thanks to all the hype and speculation, so much discussion of AI focuses on what it could be and the implications of that—cure cancer, take all the jobs, etc.—rather than what it already is, and what this alone is doing to society.

LLMs are the third algorithm of the Information Age, the third time a new internet-accessible piece of automated decision-making software changed society by changing the way people interact with information. Google search and advertisement was the first leap, algorithmic social media starting with Facebook’s Newsfeed was the second. Looking at the changes those caused can shed light on the leap we’re adapting to now.

Algorithm 1: Google Search

Debuting in 1997, Google made knowledge widely and easily accessible. The algorithm “crawled” the internet, following links to map the web’s pages and the connections between them. With automated collection and analysis of user behavior, Google provided tailored website rankings. The result is a boon to research, learning, commerce, trivia, directions — just about anything involving information.

I teach international relations, I want my students to know that the Great Depression came before WWII and why attempting to appease Hitler failed, but I don’t need them to remember the date September 1, 1939. They can look that up in two seconds. I prefer assigning essays rather than tests, because with rote memorization outsourced to computers, students can work on more complicated skills like analysis and argumentation.

Search helped people find communities and things they otherwise wouldn’t have encountered. It gave rise to new voices, including some previously shut out of mainstream discourse, and boosted valuable websites such as Wikipedia.

It also reduced respect for expertise. One popular conception of smarts pre-internet was “can rattle off a lot of facts,” but with Google, anyone can do that. Except they lack an expert’s understanding.

The other big change was advertisement. Google’s user data forms the basis of an instant, automated auction, where companies bid for your eyes. The ads that appear when you log onto a website might not be the same ads other visitors see, based on age, gender, income, interests, location, etc. Google’s algorithm estimates a lot of that, and isn’t always right, but most of the time it’s close enough to make many online ads better marketing-per-dollar than newspapers, radio, or television.

It changed a lot of business, especially media, as success increasingly depended on search engine optimization. That gave rise to click-bait, making just about all media more sensationalist, and boosted conspiracy theorists, along with other fringey figures.

Algorithm 2: Facebook Newsfeed

When social media started, feeds weren’t algorithmic. MySpace didn’t have a feed. Twitter, Facebook, etc., started with feeds of posts from users’ selected friends and/or follows, in reverse chronological order. In 2006, when it had about 12 million users, Facebook launched Newsfeed, an algorithm deciding which posts to show, and in what order.

While Google aimed to direct users where they wanted to go, so the next time they had a question they’d return to Google, Facebook aimed to keep users on Facebook. Its ads are on site, and every user action—sharing, liking, commenting, clicking, lingering on a post, whatever—refines a user profile that’s more detailed than Google’s.

Newsfeed facilitated that by selectively reordering posts from friends, and mixing in things users didn’t choose, dialing into whatever got their attention. When the website added multiple reactions in addition to “like,” Facebook found that anger generated more attention than positive reactions, and the algorithm steered into it.

Facebook became a main source of website traffic, changing the media landscape. Click-bait and sensationalism accelerated, as outlets sought Facebook virality.

Facebook Groups made it easy to organize, creating overlapping distribution networks, a valuable tool to the most funded campaign and least funded activists alike (albeit with wider spread from paid boosts). The company boosted Groups in the algorithm, promoting them as opportunities for connection.

In the process, it also helped spread conspiracy theories, false pseudoscience, and lies that are unfortunately now influential, such as antivax and QAnon. It became a vector for Russian and other foreign intelligence agencies’ influence operations, and for insurrectionists organizing Jan. 6. Facebook even facilitated mass violence, such as when false accusations against Rohingya went viral in Myanmar, fueling attacks that killed tens of thousands, and displaced hundreds of thousands more.

It impacted elections too. The Obama campaign adapted to the changed media landscape ahead of others, utilizing Facebook to gain in 2008, which carried through to 2012. Then in 2016 with the rise of Trump, Facebook and other algorithmic social media disrupted democracy. It’s been especially influential on older people, who grew up with a few trustworthy news sources, and haven’t really adjusted.

In 2012, Facebook bought Instagram, hooking it up to Newsfeed. YouTube (acquired by Google in 2006) was majority algorithmic by 2011.

Twitter went algorithmic in early 2016. That might be an underrated factor in the 2016 election, since it was the main social network for media professionals, politicians, activists, and news junkies, and the algorithm made Donald Trump the main character. In 2022, Elon Musk bought the site, turned it into X, and showed how a thumb on the algorithmic scale can make social media an engine for propaganda.

As of 2024, over half of Americans get at least some news from social media. For millions and millions of people, a computer program they don’t understand—even the programmers can’t fully anticipate or explain what the algorithms do—is their primary source of information. Few think much about that, or care.

Algorithm 3: ChatGPT

If we judge ChatGPT and other LLMs by Silicon Valley hype, they’re laughably bad. Tressie McMillan Cottom memorably dismissed AI as “mid.” But if you compare it to autocomplete, Microsoft’s Clippy, or a robotic voice going “if that is correct, press or say ‘one,’” then it’s clearly an advancement.

Google search and algorithmic social media are basically the same today as when they first got big. The companies have improved their algorithms, sometimes in reaction to changes in technology or internet behavior. Google has been enshittified with sponsored posts and now sometimes-inaccurate AI summaries, but it’s still the go-to search engine. There are more social networks than Meta’s, but all the big ones are algorithmic. The world-changing functions we got from these websites years ago are basically the same ones we get from them today.

I bet generative AI will be like that too. It won’t transform humanity with the emergence of a digital god, but it’ll alter society, perhaps as much as search and social media. We’ve had more time to see Google and Newsfeed’s impact settle in, but we can already identify areas where ChatGPT caused lasting change. Society is adjusting to that, one way or another.

Business is adopting generative AI, and some will come up with innovative ways. But the technology seems best suited to the tasks of a junior staffer or assistant: researching, coding, organizing, drafting, checking, and summarizing, with management doing oversight. It isn’t as good as the best human staffers, and might never be, but it is, as Charlie Warzel puts it, “good enough.”

Most bosses love the idea of paying fewer workers. Many will prefer a good enough AI assistant over a somewhat more capable human being that needs healthcare. Or, say, prefer paying one paralegal or programmer to use AI and achieve an output that’s close enough to three. With image generating AI, many businesses will find cheap-but-good-enough preferable to hiring a graphic designer or paying for professional photos.

I know one person who swears by LLMs’ productivity benefits, using multiple AIs in his job to brainstorm, copy-edit, create variations for comparison, and fact-check each other. Maybe people will get better at using the technology, there’ll be more applications for it, and macroeconomic benefits will materialize.

But even if generative AI stagnates here, even if companies get worse output with fewer employees, the business logic for utilizing generative AI—productivity without workers—is overwhelming.

In turn, that will increase the value of real, human-crafted material in art, writing, etc. But likely among a smaller subset of the population.

Education is the one I’m closest to, and I don’t like AI’s impact. Writing an essay is more than putting words on paper. The process of writing is one of thought-organizing. People understand something better when they put in the time and effort to write about it.

Learning, especially above the level where it’s legally required, should be an area where “good enough” isn’t good enough.

Fortunately I’ve found college students are receptive to that message—along with the warning that handing in a paper written by an algorithm gets a zero—and among hundreds of papers each semester, I’ve had very few suspicious cases. I try to craft assignments that students find interesting to think about, rather than something rote they prefer to outsource. But some might use LLMs anyway.

I’m not sure where to draw the line on partial assistance. If many jobs of the future will want people adept at generative AI, it makes sense for students to get more familiar with it in college. But even if they outsource more of their thinking to a machine than previous generations, there’s a lot of value in actually learning things first. I’d say for its own sake, and because they’ll ask more informed questions, but also because they’ll be more likely to spot when AI makes errors.

I’m curious about students who grew up with generative AI around. Current AI summaries may be good enough for most surface-level inquiries and responding to basic follow up questions. But unless employed thoughtfully, which only more sophisticated users do, AI seems bad for attention spans, art appreciation, and deeper understanding.

And the notion of instructors or TAs using LLMs for grading is ridiculous. Why would a student bother writing something no teacher will bother to read?

Misinformation was already in a golden age, and generative AI makes it worse. At the most basic level of online research, current LLMs are a downgrade from a Google search calling up a Wikipedia page. The summary from Google’s Gemini LLM is more likely to have errors, but in most cases not less likely to be believed.

More broadly, AI generates an immense amount of slop: content that’s fake, low quality, usually somewhat off, but very cheap to produce. It’s flooding the internet, drowning out other things, and getting picked up as training data for AI models, like an algorithmic ouroboros.

Some slop gets picked up in Google searches, or boosted in social media feeds, spreading it further.

One danger is people will believe the slop, especially when it validates their feelings, and fall deeper into what Renee DiResta calls “bespoke realities.” At minimum, scammers and propagandists clearly find it useful.

Another, perhaps even larger danger, is AI misinformation will become so prevalent, and appear so close to real, that people will come to doubt anything, and dismiss real evidence that makes them uncomfortable as AI fakes.

In politics, far right operatives and authoritarian governments are embracing the fakery. The low cost, ease of production, and unreality are a natural fit for post-truth political movements that try to make others live inside a lie. Generative AI is a tool for false nostalgia of a past utopia that didn’t really exist, for lying that officials making things worse have accomplished admirable feats, for confusing and frustrating people with a “firehose of falsehood,” and for acclimating them to atrocities. Gareth Watkins identified AI as “the new aesthetics of fascism.”

When floods from Hurricane Helene devastated North Carolina in 2024, Trump and VP nominee JD Vance lied about it to the point FEMA warned the lies were hindering emergency response. But the Trump campaign put out this fake AI image of Trump wading through floodwaters, the opposite of reality. It went viral on Facebook, getting tons of comments gushing about his heroic sacrifice.

The imagery isn’t convincingly real—check out Trump’s right “hand”—but it’s close enough for people who prefer validation for feelings they want to have. Especially if they’re scrolling past, not looking closely, but picking up the desired vibe.

The Trump White House and Department of Homeland Security regularly broadcast a mix of references to white supremacist literature and cutesy AI imagery celebrating rights violations and cruelty, much of which they find in the internet’s far right fever swamps. For example, DHS advertised the concentration camp nicknamed “Alligator Alcatraz”—detainees include hundreds of people who have no criminal charges—with a fake image of prison-guarding gators wearing ICE hats.

Here’s an AI-generated image they shared of a crying detained immigrant rendered in the animation style of Studio Ghibli:

The conviction that LLMs will produce AGI soon is influencing politics via the newly oligarchic power of Trump-connected tech billionaires. As Henry Farrell persuasively argues, belief in the imminence of AGI helps explain the devastating (and illegal) DOGE cuts.

After all, if you’re convinced that within a few years you can go “hey computer, cure cancer,” and it will, then why bother spending so much on human-led cancer research now? And why pay hundreds of thousands of government employees when a single algorithm will soon do their jobs better than they do? We’re just being smart, getting ahead of the impending tsunami, while other countries will be stuck with sclerotic bureaucracies when the digital genie arrives.

And don’t worry about any downsides now. “Move fast and break things.” Pay no attention to the fact that it’s mostly things these same figures wanted to break, for financial or culture war reasons, years before ChatGPT came out.

LLMs aren’t sentient, but some users believe the algorithms are, and it’s creating a sort of AI psychosis. People claim to be in love with AI chatbots, even dating them like something out of the movie Her. One reason ChatGPT-4 users are disappointed with GPT-5 is they think the tone is different, and feel like they lost a friend.

The chatbots do a lot of uncritical validation, telling people whatever they want to hear. If someone rejects scientific evidence and wants “alternative” medical advice, the bot tells them they’re right and provides some. If someone tells the bot they have a billion dollar business idea, it agrees. One user who acted on bad AI advice described the experience as “it never pushed back on anything I was saying.”

Parts of the tech elite seem especially caught up in the delusion. To pick one recent example, Uber founder Travis Kalanick claimed that he and Grok were pushing the edge of quantum physics and “pretty damn close to some interesting breakthroughs.” In other words, he asked the confirmation bias machine if together they were smarter than the world’s top physicists, and it said yes.

There’s more public focus on how we handle hypothetical machines that are actually sentient than on how we handle the psychological problems stemming from believing non-sentient algorithms are consciously intelligent. I bet we’ll find that AI psychosis has played a bigger role in the tech world’s fascist tilt than many realized.

Each of these three algorithmic leaps brought benefits, along with downsides. But while I didn’t plan on this in advance, a takeaway from this exercise is that the net societal impact of each subsequent algorithmic leap has been worse.

AI can be very efficient. That said, I refuse to use it to write even an email. The benefit of writing is it forces one to think deep and hard, and the opportunity to read how logical or otherwise your conclusion is. If AI does even the first draft, I will have to learn how the facts and figures, along with interpretative views are pieced together, making it harder to defend any positions as they are not mine to begin with.

Captures my POV precisely. I’ve been doubting the AI mania for a year, and sold all our AI-related equity several months ago. It’s clear that “model corruption” is having the same effect that click bait has had. This has the potential to damage serious AI science for years.